“But here there are just the two of us. Who are you?”

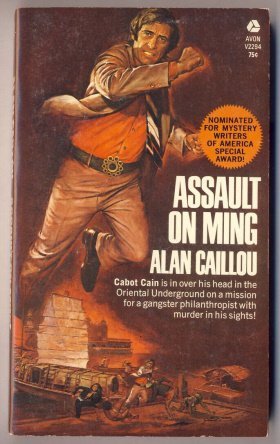

“My name is Cabot Cain. I’m a friend of your father’s.”

“And how did you get in here?”

“That doesn’t matter now. The question is, how do we get out of here?”

“We?”

“You and I.”

She hesitated, then made up her mind and reached for the telephone, but my hand was over it first, holding the receiver in place.

I said: “No, you’ll have to shoot me, and I don’t think you can afford to do that. Or even want to.”

She said scornfully: “And why not, for God’s sake?”

“Because of the others. And because you want to know what brought me here.”

The phrase the others had her worried. She was trying to listen for any noises beyond the door, trying to keep her eyes on me and at the same time see what else there was around. How could she know it was a lie? Perhaps she did; perhaps she suspected it; but she could not be sure. There was an intelligent look in those mad eyes none the less.

She said: “What brought you here? Let me guess. My father sent you to bring me home.”

“Yes, he did. Will you come?”

“No.”

“Will you let me persuade you?”

“No.”

“Will you at least talk to me, listen to me?”

“Not that either.”

I reached out quite slowly for the gun. “Give it to me. It might go off and you wouldn’t like that.” She thrust it further forward, angrily, her finger on the trigger. I shot out a hand and gripped it hard by the chamber, preventing the chamber from turning and therefore the hammer from going back; I wanted to see if she’d apply—or try to—the necessary pressure, but she didn’t. She just struggled, and took it away from her without any trouble and slipped it into my pocket. She stepped back and glared at me as though she were going to spring at me with her fingernails, ripping at my eyes, and then she opened her mouth wide to scream, but I had a band over her mouth before any sound could come; it was like closing my hand over a dry skull.

I said urgently: “I’m not here to hurt you, can’t you understand that?”

She struggled for a moment, but there was no muscle there, only skin and bone and no blood to sustain the energy. In a moment she stopped struggling and went limp, and I set her down on that overly soft and feminine sofa; her body made almost no impression on the down cushions. All the fight had gone from her. She stared at me and said:

“A year ago I could have torn your eyes out, big as you are.”

I said: “Your father wants you back, Sally. I’m here to take you to him.”

“Let him go to hell and rot, the way I’ve rotted.”

“So that’s it.”

“That’s it.”

“He’s not to blame, you know. He loves you. You’re the only thing he has.”

“Don’t talk nonsense. He’s got everything in the world except me.”

I said: “And he’s sure that his love for you is returned. He’s absolutely sure that you love him as much as he loves you.”

There was a terrible contempt in her voice: “Love him? Maybe I did, when I was a child—he tried hard enough to make me. But when I grew older, it began to fade...You don’t have to ask me why. And why should he need me? The kind of money narcotics brings in—he had everything else there was to have.”

“He gave up the drug business a long time ago.” An unlikely sort of thought came to me, and I said, not liking it: “Or did he?”

“Yes, he gave it up. He gave it up at a time when I’d learned all about it when the damage was done. It was too late then. Mr....Cain, or whatever your name is.”

“Cain is right. What do you mean, too late?”

My gun and hers tucked away out of sight. I sat beside her, keeping an eye on the other door, the one with the green drapes over it. It was an unnecessary question, somehow; I already knew what she meant.

She said scornfully: “It was easy for him to pull out. He’d collected all the millions together, and it wasn’t necessary to make more.”

“And since then, he’s spent them trying to make up for what he did in the past.”

The scorn in her voice was terrible, “He spent some of them. You mean he’s a poor man living in the gutter?”

“No, I know that.”

“He kept back plenty to live on, the way he’d always lived, only without the danger, without the excitement any more. And I’d learned, for years, that this was one way to make a dollar. And when he told me how evil it was, did he really expect me to believe that my own father, whom I’d once worshipped, was an evil man? No, of course I didn’t! It’s only now I realize just how right he was; but then it was too late.”

I said: “That’s a little bit incoherent, Sally. But you know that, don’t you?” Before she could answer, angrily, I said: “Is this your personal room?”