Sedge had held back from saying this for a long time, but he couldn’t any longer. “This never would have happened if I hadn’t moved in with you. If it would help to have me leave, I can go at any time.”

Her face drained of color and she looked at him with worry. “Why are you saying that? It’s not true! Maybe he wouldn’t have lost his fingers, but something else would have happened. Something possibly worse. I don’t want you to leave, Sedge. Please never say that again.”

On the morning she left for Echizen, they inspected the room a final time. When Sedge set on the windowsill a vase of flowers he’d collected from outside, Mariko turned to him in surprise and thanked him.

Yamanaka Onsen had been gearing up for its summer festival for more than a month. Groups around town had long been practicing their taiko routines, and in other areas he passed through, the Yamanaka Bushi song floated through the air as people rehearsed their traditional dances—Mariko included. The plaza before Yamanaka-za, too, grew busier as festival organizers strung lights overhead and arranged booths around its perimeter and the narrow streets nearby.

On the morning of the festival, Mariko woke early to drive to Echizen. She returned with Riku at one o’clock; she had met the craftsman he would apprentice with, then ate an early lunch with Riku and his grandparents. Although she and Sedge scarcely had time to talk after she came home, she summarized her morning for him and said, “I’m happy with the people Riku will have in his life. I feel better about things already.”

Rather than enter the house upon arriving, Riku went immediately into the kura, carrying cardboard boxes and masking tape for the packing he had to do.

Mariko left shortly after she got home, because her festival duties would soon begin; Yuki and Takahashi had assigned her responsibilities as a representative of their ryokan. Unable to prepare for them as much as she normally would have, she was eager to get there early. She intended to work harder than ever to help smooth over any lingering resentments, though Sedge’s leaving had seemingly resolved them.

“Riku will probably be in the kura most of the day,” she said, grabbing a bag she had prepared for herself yesterday. “After he’s done packing, it would be nice if you spent some time with him. Maybe you can help if he’s having trouble getting things done.”

“What time should I come into town?”

“Whenever you feel like it. I’ve asked Riku to be at my booth at five o’clock. It’s better to leave after he does, so he’s not here alone.”

“You don’t trust him?”

“I don’t know why I feel that way . . .”

Sedge agreed not to leave Riku unaccompanied in the house.

He watched her walk down the street. As he came back inside, he realized Riku would be here for three hours before heading to the festival. He wondered if the boy could get done what he needed to do in so short a time, especially with only one hand at his disposal.

He climbed upstairs to Mariko’s bedroom. Beside her futon lay Riku’s old school notebook, which she had found downstairs last night and intended to return to Riku today. She had shown it to Sedge, reading to him old notes he’d made for school and on his own about Bashō’s journeys and haiku.

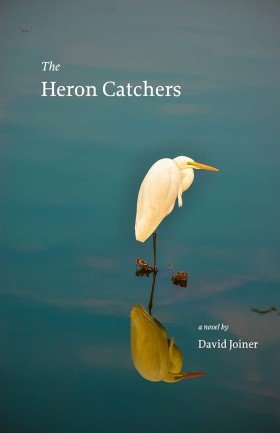

Sitting on the futon, Sedge opened it again. On the notebook’s last page were Riku’s own attempts at haiku. Only two survived without having been heavily scratched out. The first he recognized immediately from Milky Way Railroad, the Miyazawa Kenji story he and Riku had discussed two months ago.

Spring night lit with stars

The tired hunter bent over

A sack of herons

The next one referred to a heron Riku had seen in a small pond near his school. He had told Sedge once of how he watched it spear a small fish, then turn its head to the sky and swallow it.

A heron’s sharp beak

Thrusts into the clear shallows

A pond loach speared through

The poems expressed a seriousness of purpose he didn’t often associate with Riku. And though Sedge was no haiku expert, Riku’s two poems struck him as showing promise for a boy not yet seventeen. He tucked the notebook under his arm and stood up.

From the bedroom window he saw the kura’s entrance was open, and behind it cardboard boxes were heaped on the floor. The four birdhouses that had hung in front had been taken down and presumably packed away.

He lifted his eyes to the kura’s rooftop. Behind it the mountain curved gracefully, and the tops of the ancient ōsugi trees on the grounds of the village shrine trembled in the breeze. When Riku and Sedge last visited those places, Riku had been enamored with Sedge’s ability to identify any bird he saw or heard. Sedge had enjoyed their birding excursion despite the unexpected rainstorm that trapped them at the shrine. For some reason Riku had not wanted to go back. Something had come between them again, just as something had once made the boy want to kill him—Mariko. Riku had never accepted the intimate place Sedge assumed in her life. And Sedge, though he had tried to be more sympathetic to him, had grown tired of the boy’s temperament.

He wanted to help Riku grow and to learn to accept the harder things in life, both now and in the future. But he knew that such an effort would fall into the blackness of their rivalrous feelings toward each other.

Something passed by the kura entrance. As Riku dragged a cardboard box inside, he glanced up and met Sedge’s eyes.

“He’ll be gone tomorrow morning,” Sedge reminded himself. He waited a few minutes to go downstairs and greet Riku.

The sun had come out since Mariko left, and as he walked behind the house the oppressive heat made his clothes stick to his skin. Climbing the steps to the kura, he saw that the second door, separating the inside of the kura from its entryway, had also been pulled open. A small radio played Japanese rock music through tinny speakers, and he could hear objects being thrown around—not angrily, but carelessly, as Riku filled the boxes with his belongings.

Sedge knocked on the open door. The kura’s interior was much cooler than outdoors, and he took a step inside. “Mariko found one of your notebooks last night,” he said. “I have it here if you want it.”

“Leave it on the floor,” Riku muttered, not looking at Sedge.

Bending down to do as Riku said, Sedge spotted a massive pile of ashes on a strip of aluminum siding in a corner. Seeing this, he recognized in the air the faint smell of something burnt. “What’s all that ash from?” he said.

Without even glancing at what Sedge pointed to, Riku said: “My senbazuru collection.”

Sedge stared at what had been perhaps several thousand paper cranes. How many hours of work had he thrown away? How many chances to make peace later if he needed to?

“When did you burn them?”

“On the night before the heron release.”

With his feet Riku pushed his things into a tighter pile on the floor. He stopped momentarily to survey the mess around him. He had more boxes than he needed, and he began to throw whatever he could reach into whatever box that would hold it. He didn’t bother to label them. And if something stuck out, he forced it down with a foot.

Inside one box were his birdhouses, their roofs all broken off.