Thomas stood up from the bed but immediately shuddered and dropped to his knees. He put out his hands as if blind. His head twisted, and his mouth worked; his teeth creaked as he struggled against the lightning that was exploding in his head. He collapsed in the dirt.

Sìleas shrieked, but Janet hushed her. “Listen to him,” she ordered, “whatever he says. Listen well.” The girl stared back moon-eyed with fear. His jaw had relaxed. It worked as if some unseen presence was trying to make words using it. The words emerged softly.

“Striders ’cross landscapes, rivers and wild

None of them men, none e’er a child.

They who’ll have all, their brows never ringed—

Counsellors to kingdoms, never a king.”

Then he lay still and silent. “Quick, bring me my stylus and inkpot,” Janet told the girl. “There.” She pointed. Morven gurgled and whined as Janet set her aside. The babe resented her meal being removed from her grasp.

Sìleas handed Janet a feathered stylus and the small pot of iron gall. Janet repeated what she had heard, confirming with the girl that it was what he had said. Then she wrote it on the back of one of the skins piled on her for warmth. Reading it back, she muttered, “This one, I think, matters.”

“What’s it mean, ma’am?”

She shook her head. “I’m not even sure he knows. But we won’t mention it to anyone until he’s worked it out, all right?”

“He will be all right, won’t he, ma’am?” Sìleas asked, and immediately feared she’d revealed her adoration of him.

“He will. But let’s keep this between us,” Janet replied. She was fully aware of Sìleas’s infatuation.

Sìleas agreed, confused; but, superstitious, believing herself in love with Tàmhas Lynn, and in awe of the strange incomprehensible riddle, she went home and told her father of it. Lusk was aware of his neighbor’s infirmity, having chanced upon him one afternoon lying behind the plow just after a fit had finished with him. He had no idea if Thomas had spoken that day nor what Sìleas’s reported words might mean. Both of his sons listened to their sister as she recited what she remembered—it was already confused and tangling in her mind, since none of it made any sense to her. She described how it looked as if something invisible was making his mouth move and speak. The three children speculated that a devil took hold of poor Tàmhas Lynn, or maybe it was God, and the divine world touched him directly. Whatever the truth of it might be, they were more in awe of their young neighbors than ever.

That was true in particular for Filib. He had already asked if Janet might teach him writing. While that was not a skill of much use to a tenant farmer, Filib was developing ambitions beyond those of his more contented twin and his sister. He’d learned stonework and mortaring now, and how to plumb a wall; and he had begun to dwell upon the idea of the world beyond this tiny farm. Tàmhas Lynn had wandered through it and seen exciting things: battles, soldiers and kings, and many foreign places. Filib wanted to have such experiences of his own. “Striders across landscapes” probably referred to people like Thomas who traveled far and wide. People who advised kings—that’s what the riddle said, too. “None of them men or children” couldn’t mean just women. It had to be more like a reference to certain people who were special, different from the kinds of men who stayed in one place. That’s what children did: They stayed in place. The message in the riddle, he thought, had surely been meant for him.

For Thomas, though, that night was his final seizure for a long time. Three years of peace followed, as though his daughter’s emergence into the world somehow arrested the lightning in his head.

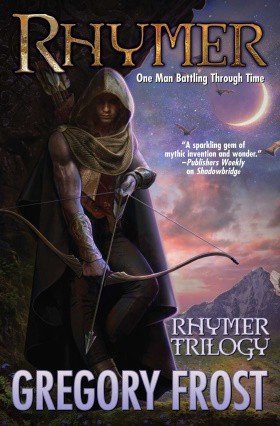

During that period, while his fits and riddles became more and more distant memories, in Ercildoun a ballad began to circulate about a lost young man with second sight who, because of his gifts, had been lured away from the world by the Queen of Elfland some seven years earlier. He was called Thomas the Rhymer.

XIX. Calligraphy

After three years of irregular practice, Filib Lusk could now produce nicely formed letters with ink and stylus. Janet provided examples for him to copy. These included some legal documents and a town charter, but mainly a bound copy of the Gospels so that he might come to recognize the words he drew. His sense of what any of it said came slowly. In part that was because in all that time Janet had provided him with just one large sheet of parchment. Each time he filled it up with writing, and they had discussed his handiwork, one of them would scrub the parchment with a paste of milk and oats, destroying the work in order to begin all over again.

His farm labor took precedence, of course, as did Tàm’s and Janet’s own lives. Between Tàm’s management of all the land under Master Cardden’s ownership, as well as farming and harvesting his own plot and the tending of his cattle, he seemed almost never to be about. Certainly, he never seemed to have an idle moment. Janet had to tend to their daughter, Morven, as well as help with the planting and harvesting. She participated in the sheep shearing, and had begun teaching Filib’s sister, dark-haired Sìleas, how to weave on her loom, often at the same time that he worked on his letters nearby. He suspected that Sìleas’s true devotion was to Tàmhas Lynn. She mooned over him whenever he was in the house with them.

Filib likewise had many duties to perform for his family. The result was that for perhaps an hour a week, he had opportunity to copy the shapes of letters and learn their sounds, and was only now beginning to understand the way that a string of them made words. From week to week it was hard to remember what he’d learned; still, the result was that he saw the shapes of letters in his head now and could sound out many of them.

He spent weeks perfecting just the writing of Dilectus a Deo from the Gospels. He wrote it up and down the parchment, covering every inch, to the point that he no longer needed to look at the original to pen the words. Janet explained the meaning of what he wrote. And he felt loved by God, too, now, though he couldn’t explain it all to his siblings. But now he could write Mattheus, Marcus, Lucas, Iojannes, and count from their books In Primo, In Secundo, In Tertio, In Quarto . . . all the way to In Decimo. After three years, what he was doing had started to make sense.

One fall afternoon a few weeks after the harvest festival, Tàmhas Lynn was up in the shieling and Janet had taken Morven out for a walk along the river, leaving Filib alone at the table with Janet’s stylus and inkpot to practice his lettering. Bored of copying the Gospels, he sat looking around for something else, and that was when he noticed the corner of a sheet of vellum sticking out ever so slightly from beneath the bed pallet. It was old and dog-eared, and had dirty lines from the boards underneath smudged across it. Under the dirt, in tight lettering, were grouped clusters of writing. There were different sizes of lines and shades of ink, which told him they’d been written at different times, sometimes with the stylus dulled and sometimes freshly sharpened; but all of it in Janet’s hand. That much he recognized. What he couldn’t decipher were the words. Whatever was written here it wasn’t the Latin he was coming to apprehend. He peered at the grouped lines—sometimes two, sometimes four or more together. He sounded out “Ercildoun” right enough, but knew none of the words around it. He tried speaking them without much luck, but an idea took hold.

The clusters of lines reminded him of a riddle Sìleas had tried to recall one night maybe three years back, just after Morven’s birth. He remembered she said that Janet had written it on the skin of a bed fur. He got up and returned to the bed, grabbed hold and flipped over the top fur. He began dragging it around and around the bed until he found the writing in one corner. It was faded, worn away in places, but it was identical to the last four lines written on the old sheet of vellum. The same words.

He placed the fur back as he’d found it, then returned to the table.

Picking up the stylus, Filib dipped it into the ink and began copying the letters as precisely as he could. One line at a time, he compared his marks to hers before continuing, and soon he had copied it all. He was especially careful with the last four lines, making sure each loop and stroke resembled the original as much as possible.

When he was satisfied with his work, he carried the vellum back and shoved it beneath the mattress. Then he sat and stared at what he’d written, concerned despite his care that it was not a good copy after all. He thought at first that when Janet got back, he would hand it to her and see how she reacted. Wouldn’t she be surprised at his skill? He chewed on his knuckle whilst staring at the parchment, and began to worry. What if this wasn’t such a good idea? She would know where the writing had come from, what it was, and would accuse him of poking through her house. No doubt the vellum had been hidden because she didn’t want anyone to find it. Surely that was true. If she caught him, she would stop teaching him, maybe even ban him for seeking out this private writing of hers. He had the urge to scrub the parchment clean before she could see it, but he had no milk paste, nothing handy to clean his writing off it. At home he could make some, scour it there. That was a better idea. At least carry it out of here before she came back and saw it.

Filib rolled up his parchment. Leaving stylus and ink on the table, he hurried out of their house. If asked, he would say that his brother had come and got him to help with carrying rye to the miller Forbes. That’s where Kester was right now, milling the grain they were going to sell in the town.

At home he busied himself roasting cakes of bannock on the firestone, and stirring the contents of the crock—whatever his mother was cooking for today—though that was Sìleas’s task. It smelled like a stew of mutton. No one would ask him how his lesson had gone. No one understood what he told them when he did, nor comprehended the lettering if he showed it to them.

He could have used some of the oats and milk he’d mixed for the bannock to scrub the parchment, but now he could not bring himself to clean it off. Instead, he folded and slid the parchment under the pillow of his pallet on the floor.

Later, in the light of the fire, he took the parchment out and stared at it. Sìleas sat with him, her brow furrowed in concentration as she tried to make out anything comprehensible in all those squiggles. She asked what it was. “A copy,” he said cryptically. She asked him what it said, and he shrugged and replied, “Dunno, it’s just writing, innit, like on any other day.” He didn’t want Sìleas thinking it was special and saying something to Janet Lynn when next she was weaving, and he didn’t want to admit he couldn’t read it. He put the parchment away under his pillow again.

Eventually, he would have to scrub it clean or show it to Janet, or burn the parchment and pretend he’d been careless. He truly didn’t want to do that. She might not give him a new piece to work with. He wanted now more than anything to know what he had written, even more intently than when he’d first started copying out the Latin words. But where could he go to have someone read it to him before his next lesson?

The answer came two days later when his father drove into Roxburgh with the sacks of milled barley and rye to sell, and Filib volunteered to go along.

“You just itching tae get out of chores, boy?” his father asked.

“No, sir. Done ’em, every one. Mucked out the livestock, too.” With a nod, Mrs. Lusk confirmed this was so.

“Did ye, then? Good lad.” Lusk threw his arm around his son’s shoulders and walked him outside. “Well, then. Off tae market, and then we’ll have us a wee stop at the alehouse after.” His father winked at him.

Filib ran back inside, grabbed his parchment, and wrapped it around his forearm, hidden up under his sleeve.

In the alehouse, The Blind Fiddler, his father bought them each a mug, then settled him at a small table and abandoned him for some friendly, familiar faces farther back. Filib found himself seated beside the door, alone and regretting that his brother hadn’t come along, too; but Kester had been in the river, fishing for their meal tonight.

The parchment up his sleeve began to itch. He needed to find somebody who might read it.

He was looking around when the door from the street opened, drawing his attention. Sunlight flashed for a moment before the door beside him closed. Filib blinked in the aftermath of brightness. He was staring up at a man who gazed down upon him as if in judgment an instant before striding through the room. There, he thought, went the perfect person to ask—a professional man, learned, and what was more they had even met, though he doubted the magistrate would remember. It had been in July when he and father were selling the wool they’d just sheared to someone at market who was buying wool to ship to Flanders, and the magistrate was officiating in the sales. Filib knew that he could read and write. He had to.