“Oh, he thinks that I am staying with Silvana. She will come and get me early, before he comes with your mail. We know his schedule to the second.” She tangled her legs with his. “Sleep a little. We will have your lovely dinner at midnight.”

And so they did, with Bianchi in his father’s old bathrobe, and Giovanna in the flowered nightgown she had brought in her backpack. Sitting across from him, with her legs curled under her, the gold-flecked green eyes happily heavy and her hair like a bird’s nest, she pronounced the meal exquisite, the flowers perfect, the Ciro the best wine she had ever tasted, and his ancient robe adorable. When he asked hesitantly, “Have you been . . . thinking about this for a long time?” she giggled like a schoolgirl at first; but then she looked down at the table and nodded. He said, “About me?”

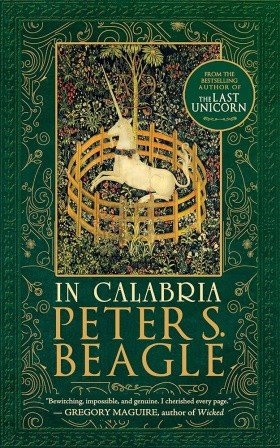

“And what is so astonishing about that, Signor Claudio Bianchi? Unicorns come to you all the time—why shouldn’t a woman?” Her eyes were not at all heavy then, but wickedly tender. Bianchi looked away from them.

He said, “I was married once.”

“Yes. Romano has told me. And she left you. So?”

“She was right to leave me. I was not good at being married.”

“Bianchi,” she said. “Claudio. Marriage isn’t like football, like bocce. One isn’t good at it, nobody has a special gift. You stumble along, and if there is enough love—” she smiled at him—“you learn.”

Bianchi got up from the table abruptly enough that Giovanna’s eyes widened. He turned in a circle, like a captive animal—a bear or an elephant—and then he stood leaning with his hands on the back of his chair. “There is no love in me. There is nothing to be learned. She would have stayed if there were, but she knew. I am just telling you now.”

“A unicorn has stayed.”

Bianchi was silent for a moment. “La Signora chose my farm because she felt it would be a safe place to have her baby. Not because of me.”

“You think not?” Giovanna’s expression was a curious mixture of exasperation and affectionate amusement. “You think a unicorn would not know—would not know—who would come out of his house in a storm to help her in her trouble? To perhaps save her child’s life? You think unicorns don’t know such things, Bianchi?”

Bianchi turned his back to her, his shaggy head lowering. “Unicorns know nothing. Otherwise she would never have let me near her.”

Giovanna waited, unspeaking. Bianchi was doing something with his hands that she had seen him do before, the fingers of the left hand hooking over the right knuckles, squeezing rhythmically, so hard that she winced to see it. Bianchi said, “You don’t know anything, either.”

“Well, I know exactly where you are ticklish,” she said. “How many people have ever known that?”

When he finally sat down at the table again, she reached for his hand, but he pulled it away, folding his arms in front of him. He said, “I pulled another child from its mother’s belly once. Long ago. So long ago that it feels as though it happened to someone else. But it happened to me—and to her.”

Giovanna placed her own hands flat on the table, close to his, but not touching. “Your child died?”

Bianchi nodded. “If there had been a doctor . . . But it was night, and we had no money, and after all, I knew how to deliver a calf, a puppy—a goat, even. She was safe with me.”

“And she never forgave—” Giovanna stopped herself, the green eyes widening. Slowly she said, “No . . . no, she forgave you—but you . . . ay, Bianchi. Bianchi.”

“It was long ago, I told you,” he answered indifferently. “One goes on. One gets . . . used to things.”

As if I could ever get used to your touch, ever get used to your lovely cold feet in my bed—get used to another person, ever again, at this table where I eat my meals and write my poems. Get used to the way I will feel when you leave in the morning.

“But you do not go on,” she said. “You stay exactly where you were, that night when your child died.” Bianchi sat motionless, but he clenched his hands on his wrists, and she could see that he was shivering. After a silence filled with each other’s eyes, she said in a surprisingly small voice, “My friends call me Gio. You could call me that, if you like.”

“Gio,” Bianchi said. “Gio. All right.”

She fell asleep as soon as they went back to bed, snoring daintily on his shoulder and holding him so tightly that it was almost painful. But when hesaid, “She did not leave me because of the baby, but because of what you said—because I could not, could not . . .” she woke up immediately and answered, “E allora? More fool she.”

“No,” he said. “No, she was not a fool, she was wise to leave,” but Giovanna was asleep again.

Bianchi stayed awake all night, inhaling her closeness, listening to the soft sounds her body made, thinking, can you write a poem about someone’s snores? About trying not to sneeze when her hair tickles my nose? About that one tiny, barely audible fart against my leg? What will I write at my kitchen table, now that she has been there, drinking my wine and eating the dinner I made for her? Late to be discovering all this, Bianchi—all this that children know about these days. Very, very late . . .

There would have been time for breakfast, as he had envisioned, but for the spirit in which she awoke. They were barely dressed before they heard the sputter of the motorscooter. Giovanna peeped through the door, waved to Silvana while stuffing her nightgown into her backpack, and kissed Bianchi hard enough that their teeth clattered together and brought blood from her lower lip. She touched her finger to the blood, and then to the tip of his nose. “There, so you’ll know I will come back,” and she was out and gone, smiling at him from the back of the Vespa. Silvana waved too.

Bianchi moved slowly for the rest of the day. He let the three cows out to graze, fed the pigs and checked the security of their pen, as he did every day, and irrigated his fields and trees for the first time since the rains ended, reminding himself to replace two of the water hoses. But for all that, he was still absent from his activity, not thinking even about Giovanna . . . Gio . . . but rather savoring the calmness in his skin that had nothing to do with work, or spring, or poetry. “So you’ll know I will come back . . .” Sometimes he smiled vaguely, just for the sensation of the bruise on his own mouth.

Romano, who arrived with an electricity bill and a new Dell’Acqua fashion catalogue, said after one glance, “It is obviously an epic that has carried you off. Something about the days of the Carbonari? About football? Unicorns?” He turned in all directions as he spoke, gazing hopefully everywhere but at Bianchi.

“No poem.” Bianchi replied. “No unicorns.”

“Perhaps that would be a good thing,” Romano said. “I have been hearing . . .” He did not finish, but began rooting earnestly in his mail pouch, as though in futile search of an actual letter. The back of his neck looked to Bianchi as young and vulnerable as his sister’s neck.

“You have heard what? Tell me.” Bianchi’s stomach knew what was coming, but he himself needed the words.

“Those people . . .” Romano still did not turn.

“What people? The ’Ndrangheta? Say it, Romano.”

“Barbato,” Romano mumbled. “The one who sells flowers on the Via Cavour? Marco, his son, he’s not in the ’Ndrangheta, you understand, but he does favors for them sometimes—just a few favors.” He did turn to Bianchi then, and his face was more taut and strained than the older man had ever seen it. “But it will be all right, if the unicorns are really gone. I can spread the word—I go everywhere, you know that—and they won’t want your land then. I can do that.”

Bianchi put his hands on the postman’s shoulders. “Pace, fratello mio. The ’Ndrangheta have had plenty of time to come after me, and they have not done so. They are drug traffickers, arms dealers, extortionists—why would they waste time on rumors of a couple of mythical beasts perhaps seen on one ignorant farmer’s wretched few hectares? Whatever else they are, they are not stupid.”

But the words sounded bodiless even to him, and he could have spoken Romano’s response along with him. “No—but you are, if you think they have finished with you. They have only begun, Bianchi.”

Cherubino, who was afraid of the mail van, came up as it rumbled away and nudged familiarly against Bianchi, on the chance of there being something for him in the faded work shirt. Bianchi scratched him absently behind the horns, thinking, would they hurt the animals? Even the ’Ndrangheta surely wouldn’t hurt a three-legged cat. He realized that his hands were cold and trembling, and he shoved them into his pocket. Yes, they would. Yes, they would. And they would hurt her, if she were here . . .

This time, when they spoke that night, he made it an order, not a warning. “You are not to come here again—not ever, not for any reason. If I see you here, I will send you right away, even if there is no trouble. Do you understand me?” When she did not answer, he repeated, “Do you understand me? Gio?” He was still oddly shy about using the intimate nickname.

“I am nodding,” she said flatly. “I am not saying yes. Do you understand the difference?”