“Washout,” the man at her window said.

“It hasn’t rained in days.”

“Road construction, then. Take your pick. You’re not coming through.”

“We’ll just park here and walk.”

“Wouldn’t do that, if I were you,” the man on Annie’s side said.

“Why not?” Annie asked.

“Can’t guarantee the safety of your vehicle.”

“What exactly might happen to it?” Rainy said.

“Never can tell. Lots of questionable types around here these days. Vandalism, theft, you name it,” the man on Rainy’s side said.

“I think we’ll just go around the barricade and take our chances with the washout and the road construction,” Rainy said.

“We don’t need more Indians screwing up our jobs,” the man at Annie’s window said.

“And we don’t need more oil spilling on our land and screwing up our water,” Annie replied without heat.

The man at her window squinted. “You ain’t even Indian. What do you care?”

“Every sentient person cares about Mother Earth.”

“Sentient? What the hell does that mean?”

“It means a thinking, feeling person. But let me ask you a question. When you were a child, what would you have done if somebody dumped a thousand gallons of oil on your backyard?”

“Nobody did.”

“But that’s what might happen to my backyard here.”

“It already has happened,” Rainy said. “Twice. A million gallons in 1973, and nearly two million gallons in 1991. So you understand our concern.”

“All I know, lady, is while you do your shit here, I’m not getting paid. I got a family to support.”

“Seven generations,” Rainy said.

“What?”

“Try to think ahead seven generations. What you’re doing here will have an effect long after you’re gone.”

“You’ve got ten seconds to turn around,” the man at Rainy’s window said.

“Then what?” Rainy asked, her voice full of iron.

“I think we report that some vandals beat the hell out of your car and maybe you three along with it.”

The man at Annie’s window gave a sharp whistle and beckoned to the others at the barricade. The half dozen men made a semicircle around the front of the car. Two of the men carried iron pipes. One of them swung his pipe, and Annie heard the shattering of headlight glass.

“That’s your last warning, lady,” the man at Rainy’s window said.

Several of the men were grinning, as if this were a game and they were ready for more fun.

Then the man who’d bent to Annie’s window suddenly straightened up. “Cops,” he said.

Annie heard the chirp of a siren from behind, not a full blast, just enough to announce an approach. She heard a car door slam, and a moment later, a uniformed deputy stepped up to Rainy’s window. The man from the barricade backed away to give the deputy room.

“Boys,” the deputy said. “Just go on back to your station.”

The men cleared away from the car.

The deputy leaned toward Rainy. “Everybody okay in there?”

“They shattered my headlight,” Rainy said.

The deputy nodded and thought for a moment.

“Ma’am,” he said. “If I write this up, it’ll mean you have to come back and go through a lot of legal hoops, and I’m pretty sure that these men are going to stick to some story that contradicts everything you say. It’ll be a long and drawn-out process, and in the end, it’ll be more trouble than it’s worth. How about I just make sure you get beyond this barricade?”

“What about when we come out?”

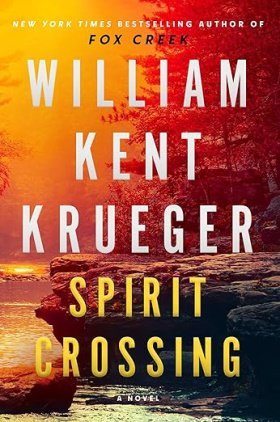

“I guarantee they won’t stop anyone leaving Spirit Crossing. Okay?”

“Okay,” Rainy said.