An etching of Lady Huntingdon was placed by Washington in his Mount Vernon Estate following her death

.

The Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion was part of the eighteenth century Evangelical Revival closely associated with John Wesley and George Whitefield. Although touching the upper class, it was a religious movement that touched the local population as well. It had a college for the training of ministerial skills and established several interconnected chapels in England. Following the pattern of Wesley, the movement, although originating in the Anglican fold, eventually seceded, and The Connexion became a denomination of its own with its own creed and ordination.48

Washington’s first connection with “Lady Huntingdon’s Connexion” was probably in late 1774, either during or just after his return from the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. In his diary for 1774, November 5, we read: “Mr. Piercy a Presbeterian [sic] Minister dined here.” It is possible that Washington had met Piercy while in Philadelphia. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Thwohig, editors of Washington’s Diaries write,

Mr. Piercy was probably William Piercy (Percy), a Calvinistic Methodist and disciple of George Whitefield. Piercy was chaplain to Selina Hastings, countess of Huntingdon, a devoted follower of the new Methodist movement. In order to give protection to Methodist preachers, she appointed large members of them to the nominal position of chaplain in her household. She had sent Piercy from London to Georgia in 1772 to act as president of Whitefield’s Orphan House, or college, at Bethesda, near Savannah, and to preach wherever he could collect an audience in the colonies. Piercy had preached at various locations in Philadelphia during the year. He had given a farewell sermon in late October at the Arch Street Presbyterian meetinghouse, and was probably at this time on his return to his headquarters in Georgia.49

The day after Piercy’s visit was Sunday, and Washington’s diary says, “November 6. Went to Pohick Church.” From this point on until the end of the Revolutionary War, there is no mention of Lady Huntingdon’s ministry in Washington’s writings.

However, at the conclusion of the American Revolution, Washington heard personally from Lady Huntingdon, who wrote to him in 1783, when she was seventy-six years of age. Unfortunately, while her February 20, 1783, letter is not extant we do have Washington’s letter in response that allows us to construct what the Countess had in mind. Washington responded to Lady Huntingdon’s letter from Headquarters on August 10, 1783:

My Lady: Within the course of a few days I have received the Letter you was pleased to Honor me with from Bath, of the 20th of febry. and have to express my respectful Thanks to your Goodness, for the marks of Confidence and Esteem contained therein.

Your Ladyships benevolent Designs toward the Indian Nations, claim my particular Attention, and to further so laudable an Undertaking will afford me much pleasure, so far as my Situation in Life, surrounded with many and arduous Cares will admit. To be named as an Executor of your Intentions, may perhaps disappoint your Ladyships Views; but so far as my general Superintendence, or incidental Attention can contribute to the promotion of your Establishment, you may command my Assistance.

My Ancestry being derived from Yorkshire in England, it is more than probable that I am entitled to that honorable Connection, which you are pleased to mention; ...50

The Lady’s letter had obviously asked Washington to be an executor of her missionary plan to the Indians, and in the same letter had proposed the possibility that Washington and Lady Huntingdon were related. Historians have established that the common ancestor of the Countess and Washington was Lawrence Washington of Sulgrave Manor (1500-1584).51 But Washington, true to form, never bothered to establish the connection.52 Yet Washington was interested in the Countess’ mission to the Indians. Although his plans for retirement prevented taking on the task of executor, he pledged himself to her cause “so far as my general Superintendence, or incidental Attention can contribute to the promotion of your Establishment, you may command my Assistance.”53

This offer of assistance was more than enough for the royal Lady’s purposes. She wrote back on March 20, 1784, with striking words. She did not merely call upon Washington to assist her in her American version of her Gospel Connexion, namely, the evangelization of the Indians; instead, she addressed him with Messianic terms as she boldly applied the biblical texts of Isaiah 41:2 and 8 to the triumphant American commander in chief. If Washington were a Deist, this would have been a most awkward misunderstanding. Lady Huntingdon wrote,

Sir, I should lament the want of expression extremely did I believe it could convey with the exactness of truth the sensibility your most polite kind and friendly letter afforded me. Any degree of your consideration for the most interesting views of my grant which stands so connected with the service of the Indian nations eminently demands my perpetual thanks.

No compliments can be accepted by you, the wise providence of God having called you to, and so honoured you in, a situation far above many of your equals. And as one mark of His favour to His servants of old was given—“the nations to your sword and as the driven stubble to your bow” [Isa. 41:2]—[this] allows me then to follow the comparison till that character shall as eminently belong to you—“He was called the friend of God.” [Isa. 41:8]. May therefore the blessings obtained for the poor, so unite the temporal with the eternal good of those miserable neglected and despised nations that they may be enabled to bless you in future ages whose fatherly hand has yielded to their present and everlasting comfort.

I am obliged to say that no early or intemperate zeal, under a religious character, or those various superstitious impositions, too generally taken up for Christian piety, does in any measure prevail with my passions for this end. To raise an altar for the knowledge of the true God and Jesus Christ whom he hath sent “where ignorance alike of him and of themselves so evidently appears” is my only object. And this to convey the united blessings of this life, with the lively evidence of an eternity founded on the sure and only wise testimony of immutable truth is all my wants or wishes in this matter. And my poor unworthy prayers are for those providences of God that may best prepare the way to so rational and great an end.54

How would a Deist answer this biblical plea to help an evangelical establish Christian missionaries “to raise an altar for the knowledge of the true God and Jesus Christ”? While various letters between the Countess of Huntingdon and Washington have not survived, we do have several which establish Washington’s views of Lady Huntingdon’s Gospel mission to the Indians. His responses are those of a Christian. Washington wrote to Lady Huntingdon on February 27, 1785,

My Lady: …With respect to your humane and benevolent intentions towards the Indians, and the plan which your Ladyship has adopted to carry them into effect, they meet my highest approbation; and I should be very happy to find every possible encouragement given to them. ….I have written fully to the President of Congress, with whom I have a particular intimacy, and transmitted copies of your Ladyships plan, addresses and letter to the several States therein mentioned, with my approving sentiments thereon. …55

Writing on January 25, 1785, to Sir James Jay, friend of the Countess and the brother of American political leader John Jay, Washington says,

I am clearly in sentiment with her Ladyship, that Christianity will never make any progress among the Indians, or work any considerable reformation in their principles, until they are brought to a state of greater civilization; and the mode by which she means to attempt this, as far as I have been able to give it consideration, is as likely to succeed as any other that could have been devised…As I am well acquainted with the President of Congress, I will in the course of a few days write him a private letter on this subject giving the substance of Lady Huntington’s plan and asking his opinion of the encouragement it might expect to receive from Congress if it should be brought before that honorable body. …Without reverberating the arguments in support of the humane and benevolent intention of Lady Huntington to Christianize and reduce to a state of civilization the Savage tribes within the limits of the American States, or discanting upon the advantages which the Union may derive from the Emigration which is blended with, and becomes part of the plan, I highly approve of them…56

Writing to Richard Henry Lee, the President of the Congress on February 8, 1785, Washington explains:

Towards the latter part of the year 1783 I was honored with a letter from the Countess of Huntington, briefly reciting her benevolent intention of spreading Christianity among the Tribes of Indians inhabiting our Western Territory; and Expressing a desire of my advice and assistance to carry this charitable design into execution.…Her Ladyship has spoken so feelingly and sensibly, on the religious and benevolent purposes of the plan, that no language of which I am possessed, can add aught to enforce her observations. …57

Writing finally with the disappointing news of lack of success to the Countess of Huntingdon on June 30, 1785, Washington explained that resistance to the plan had been encountered in Congress for various reasons, including the concern of placing British subjects on America’s frontier as a possible future source of political destabilization:

My Lady: In the last letter which I had the honor to write to you, I informed your Ladyship of the communication I had made to the President of Congress of your wishes to obtain Lands in the Western Territory for a number of Emigrants as a means of civilizing the Savages, and propagating the Gospel among them. …I will delay no longer to express my concern that your Ladyships humane and benevolent views are not better seconded.58

Nevertheless, when General Washington became President Washington, he continued to view “a System corresponding with the mild principles of Religion and Philanthropy towards an unenlightened race of Men” to “be as honorable to the national character as conformable to the dictates of sound policy.”59

The last we hear of Lady Huntingdon in Washington’s writings is on January 8, 1792. Washington wrote a brief note of acknowledgment to Robert Bowyer for an engraved portrait print of the Countess of Huntingdon, made from Bowyer’s painting.60 The Countess had died the year before. Obviously Washington did not want the “connection” with Lady Huntingdon to end. We honestly wonder how many Deists through the years have secured engraved portraits of the world’s great Christian missionaries and evangelical philanthropists.

WASHINGTON’S VIRGINIA ROOTS

Washington was an American and a Virginian. He never forgot his rich legacy. In the first draft of his Farewell Address, President Washington accented his roots:

I retire from the Chair of government . . . I leave you with undefiled hands, an uncorrupted heart, and with ardent vows to heaven for the welfare and happiness of that country in which I and my forefathers to the third or fourth progenitor drew our first breath.61

In fact, when he was retiring, our first president attempted to trace his roots. He was asked by a high ranking British official for this information. So on November 15, 1796, when he was in Philadelphia, George Washington wrote to his nephew, Captain William Augustine Washington:

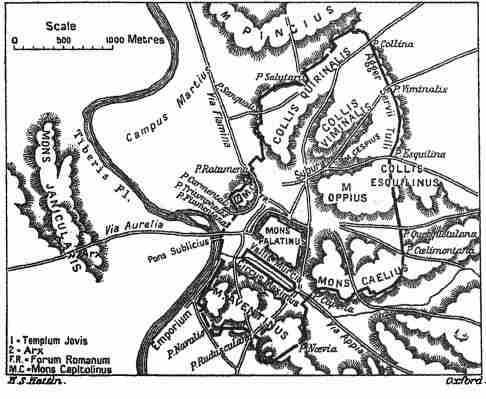

Without any application, intimation, or the most remote thought or expectation of the kind, on my part; Sir Isaac Heard, Garter and principal King at Arms, wrote to me some years since enclosing our Armorial [coat of arms]; and requesting a genealogical account of our progenitors since the first arrival of them in this country. …and although I have not the least Solicitude to trace our Ancestry, yet as this Gentleman appears to interest himself in the research, common civility requires that he should obtain the aids he asks, if it is in our power to give it to him. Let me request of you, therefore, to give me what assistance you can to solve the queries propounded in his letter, if you have only old papers which have a tendency towards it: if not, or whether or not, by examining the Inscriptions on the Tombs at the Ancient Vault, and burying ground of our Ancestors, which is on your Estate at Bridges Creek. And if you are able to do it, trace the descendents of Lawrence Washington who came over with John, our Progenitor. 62

Tomb stone placed by Washington’s family on the crypt several years after his death with the inscription from John 11:25.

In other words, Washington was asking his nephew for help in tracing his roots back to England, including reading tombstones, if necessary. Although Washington had no personal interest in his family’s genealogy, he had already been thinking about his ancestors’ tombstones for over a decade. On December 18, 1784, Washington wrote that he “might soon expect to be entombed in the dreary mansions of my father’s.”63 We don’t know what inscriptions Washington’s nephew found on the tombs of their early Virginian ancestors. But we do know what Washington’s ancestors ultimately put on his Mount Vernon tomb. Should you visit Washington’s tomb at Mount Vernon, you will read “I am the resurrection and the Life.” (John 11:25), the very first words of the funeral service in the Book of Common Prayer. Strange indeed that the immediate descendants of a Deist would have a Gospel text quoting Jesus’ teaching on the resurrection on the alleged Deist’s tomb! Either Washington’s heirs were quite confused about the faith of Virginia’s greatest son, or they knew George Washington’s faith better than most recent historians do.

CONCLUSION

Thus, the tapestry of early Virginia was intricately interwoven with the commerce of tobacco production, a sincere commitment to the church and the Christian mission to the Native Americans, alongside the tragic realities of trading in slaves, the assimilation of convicts and conflict with Native Americans. It was to this faltering yet consciously Christian colony that Washington’s family emigrated some fifty years after the establishment of Jamestown. Accordingly, Washington’s life was deeply marked by the culture and values of Virginia, “that country in which” he and his “forefathers to the third or fourth progenitor drew” their “first breath.”64 Whether as General, a private citizen, or as president, Washington never swerved from an expressed commitment to the Christian evangelistic mission to the Native Americans that was a legacy bequeathed to him by the very first Anglican settlers of the colony of Virginia. The skeptics who argue for Washington the Deist must explain his lifelong and heartfelt commitment to Christian missionary work. Moreover, nothing less than both written evidence and recorded deeds from Washington himself will be sufficient to explain how he could simultaneously explicitly advocate Christian missionary evangelism, and yet as a Deist deny the teachings of Christianity.

FIVE

George Washington’s Virginian Ancestors

“Honour and obey your natural parents altho’ they be poor.”

Rule of Civility: 108th Copied by George Washington in his school paper. c.1746