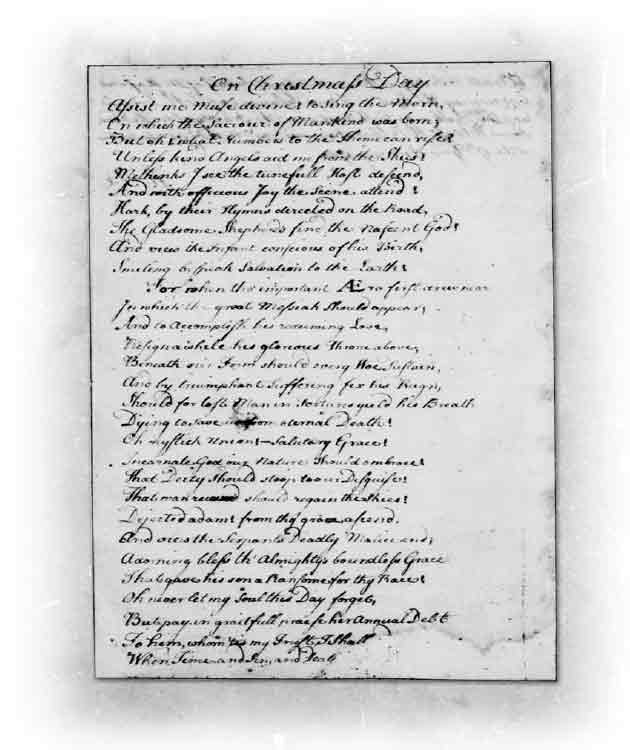

To Him whom ’tis my trust I shall [adore(?)—illegible.]

When time and sin and death [shall be no more.(?)—illegible.]38

Based on this traditional Christian childhood education, Washington’s adult writings show that he maintained a deep joy in the Christian celebration of the birth of Christ.39

GEORGE WASHINGTON’S “RULES OF CIVILITY”

Virtually all scholars, even those who believe Washington was not a Christian, agree that a set of sayings, originally composed by a Jesuit priest from a century before and often embellished thereafter, was very influential in George Washington’s education.40 This set of 110 sayings contains many biblical precepts. They are the “ Rules of Civility and Decent Behaviour in Company and Conversation”41 and are viewed as a blueprint that Washington followed his entire life. They are given in their entirety in appendix One.42

They were, in fact, very important in the training of students at the Appleby School where George’s father and stepbrothers had attended. William Wilbur writes,

George’s father was very familiar with these rules, for they were used at Appleby Grammar School. Among English educators they were generally referred to as Hawkins’ rules. They had wide acceptance in English schoolrooms and were so popular that eleven editions were printed between 1640 and 1672. . . the correct title is: “Youth’s Behaviour or Decency in Conversation Amongst Men.” The title page runs on, “Composed in French by grave persons for the use and benefit of their Youth. Now newly turned into English by Francis Hawkins.”43

Although we will list only a few of them here, these remarkable and at times humorous rules, as William Wilbur suggests, all fall into the following categories:

RULES Which Taught Character.

Christmas poem reflecting a rich understanding of the doctrine of salvation in Christ written in Washington’s hand

RULES Which Counseled Consideration for Others.

RULES That Urged Modesty.

RULES That Advised Compassion.

RULES That Enjoined Respect for Elders and Persons in Positions of Responsibility and Authority.

RULES Which Concern Conduct.

RULES Governing Table Manners and Cleanliness.44

Here are a few of the rules. Immediately following, we have supplied a biblical text, of which this maxim is an echo:

RULES OF CIVILITY: 43d Do not express Joy before one sick or in pain for that contrary Passion will aggravate his Misery.

BIBLE: Rejoice with those who rejoice, and weep with those who weep (Romans 12:15, NKJV).

RULES OF CIVILITY: 48th Wherein you reprove Another be unblameable yourself; for example is more prevalent than Precepts.

BIBLE: “Judge not, that you be not judged. For with what judgment you judge, you will be judged” (Jesus in Matthew 7:1-2, NKJV).

RULES OF CIVILITY: 56th Associate yourself with Men of good Quality if you Esteem your own Reputation; for ‘tis better to be alone than in bad Company.

BIBLE: “Evil company corrupts good habits” (1 Corinthians 15:33, NKJV).

RULES OF CIVILITY: 82d Undertake not what you cannot Perform but be Carefull to keep your Promise.

BIBLE: When you make a vow to God, do not delay to pay it; for He has no pleasure in fools. Pay what you have vowed—Better not to vow than to vow and not pay (Ecclesiastes 5:4, 5 NKJV).

RULES OF CIVILITY: 108th When you Speak of God or his Atributes, let it be Seriously & [wt.] Reverence. Honour & Obey your Natural Parents altho they be Poor.

BIBLE: Holy, holy holy is the LORD of hosts (Isaiah 6:3).

You shall not take the name of the LORD your God in vain, for the LORD will not hold him guiltless who takes His name in vain....Honor your father and your mother... (Exodus 20:7, 12, NKJV).

RULES OF CIVILITY: 109th Let your Recreations be Manfull not Sinfull.

First and last pages of the Rules of Civility, Washington’s rules for life.

Note: The 1828 dictionary of Noah Webster defines manful as “noble, honorable.”

BIBLE: Flee also youthful lusts... (2 Timothy 2:22, NKJV).

RULES OF CIVILITY: 110th Labour to keep alive in your Breast that Little Spark of Ce[les]tial fire Called Conscience.

BIBLE: Now the purpose of the commandment is love from a pure heart, from a good conscience, and from sincere faith (1 Timothy 1:5, NKJV).

Many of these dignified principles can be summed up in Christ’s golden rule: “Whatever you want men to do to you, do also to them.” (Matthew 7:12). George Washington not only read the Golden Rule on the rerodos of the church in Alexandria, he quoted it on occasion.45 These “Rules of Civility” speak volumes about the shaping of the character of George Washington. Marvin Kitman, notes of the “Rules of Civility:” “Those few hundred didactic words say as much about what makes the man tick as multi-volume biographies.”46

THE YOUNG MAN’S COMPANION BOOK

Along with these most remarkable character values in the Appleby School and “Rules of Civility,” there was another text that was a standard for English schoolboys from the late sixteen-hundreds to the end of the seventeen-hundreds. These are the various editions of The Young Man’s Companion textbooks. Grizzard refers to the 1727 edition by George Fisher, published in London, from which some of the lessons in Washington’s papers were taken.47 Joseph Sawyer mentions yet another The Young Man’s Companion written by W. Mather in 1742 and published in England, which “was in its thirteenth edition when owned by Washington. He scrawled his name on the flyleaf of his copy, which is said to have been owned, a century later, by General Ulysses S. Grant. There is probably no copy of the book available in this country today—if anywhere.”48 We here consider passages from the text to appreciate what William Mather was trying to accomplish on behalf of his young masculine readers.

While each edition had its own unique content, there was a common message and spiritual continuity in the various editions. Mather’s desire was to bring all sorts of useful knowledge to his young readers in the context of a devout Christian faith. William Mather’s 1681 edition, for instance, is entitled A Very Useful Manual or the Young Man’s Companion, and is 411 pages in length. It contains “plain and easy directions for spelling, reading, and uniting English with easy rules for their attaining to writing, and arithmetick, and the Englishing of the Latin Bible without a Tutor....” Mather writes “To the Reader” giving as his fourth point, “Those that desire to live and walk in the true Religion, must above all heed the outward Teachings, mind the Reproofs of the Spirit of Truth in their own Hearts against all Sin and Evil, otherwise they will turn to the Right Hand, or to the Left into evil. Isa. 30.20, 21, Gen. 6.3, John 3.19.” He concludes his introduction by calling for his readers to bring glory to God and by adding this rhyme: