It is true that as a young man and for much of Washington’s adult life, Virginia had an established church—the Anglican Church. By law one was required to attend services and pay tithes. That was part of the responsibility of a colonist in Virginia. However, that changed in 1786 with the Act for Establishing Religious Liberty. This great step forward in terms of religious liberty was especially the work of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

One of the key arguments Jefferson made in this statute was that Almighty God has made the mind free and that any punishments that men mete out against religious opinion deemed to be false are a departure from “the plan of the holy author of our religion, who being lord both of body and mind, yet choose [sic] not to propagate it by coercions on either, as was in his Almighty power to do, but to exalt it by its influence on reason alone…”28

In other words, Jefferson argues, because Jesus Christ could have forced men to believe in Him, but did not, and instead gave us the personal responsibility to believe, then who are we as mere men to punish others for their religious opinions, no matter how wrong these opinions may be? Secularists sometimes interpret Jefferson’s argument here as a plea for unbelief. Not so. He uses the example of Christ to argue for religious freedom. In fact, religious liberty in America especially stems from two great Christian clergymen who prepared the way for America’s religious liberty. They were also two of our nation’s settlers—Roger Williams and William Penn.

After Virginia disestablished the Anglican Church, men and women were no longer required by state law to worship there. But Washington did not stop attending church after disestablishment. He kept attending his church long after that—until he died.

GOD IN THE SPEECHES AND WRITINGS OF WASHINGTON

George Washington’s mention of God in his private letters as well as his public speeches and writings is frequent, especially when we understand the vast variety of terms he employed for the Almighty including, “the great disposer of events,” “the invisible hand,” “Jehovah,” or his favorite term—“Providence.” We cannot escape the alternatives—Washington either truly cared about God or he employed God-talk for mere political or manipulative ends, while he himself didn’t believe the words he was speaking. The latter appears difficult to accept from a man who insisted, “Honesty is the best policy.”

We are all familiar with politicians talking about God in their public speeches—even if their private behavior belies that God-talk. Was George Washington this type of public figure? We don’t think so, nor does the historical evidence support it.

Boller quotes a nineteenth century Anglican minister who laments that Washington allegedly never mentioned Jesus. Anglican minister Bird Wilson said, “I have diligently perused every line that Washington ever gave to the public, and I do not find one expression in which he pledges himself as a professor of Christianity.”29 Here is a sampling of what Bird Wilson could have perused. Washington said that America will only be happy if we imitate “the divine author of our blessed religion.”30

This is referring to Jesus Christ. This was not an obscure letter; it is the climax of a critical farewell letter the commander in chief wrote to the governors of all the states at the end of the War. Furthermore, it seems that Wilson didn’t know about the letter General Washington wrote to the Delaware Indian chiefs. They asked him for advice on teaching their young ones. He responded that they do well to learn our way of life and arts, “but above all, the religion of Jesus Christ.”31

Furthermore, Washington talks about the need to be a good Christian, using the word “Christian” in several different letters and communiqués. Thus, we find phrases such as the following in Washington’s public and private writings: “A Christian Spirit,” “A True Christian,” “Be more of a man and a Christian,” “Christian soldiers,” “The little Christian,” “To the distinguished character of Patriot, it should be our highest glory to add the more distinguished character of Christian.”32

What makes these affirmations of Christianity personal for Washington is his deeply held view that strong leadership must be coupled with consistency and integrity. One of Washington’s “Rules of Civility” comes into play here.33 The forty-eighth says, “Wherein you reprove another be unblameable yourself, for example is more prevalent than precepts.” Thus he wrote to Lord Stirling, March 5, 1780, “Example, whether it be good or bad, has a powerful influence, and the higher in Rank the officer is, who sets it, the more striking it is.” He wrote as follows to James Madison, March 31, 1787, “Laws or ordinances unobserved, or partially attended to, had better never have been made; because the first is a mere nihil [utterly useless], and the second is productive of much jealousy and discontent.” He also wrote to Col. William Woodford, November 10, 1775, “Impress upon the mind of every man, from the first to the lowest, the importance of the cause, and what it is they are contending for.” And writing to James McHenry on July 4, 1798, he declared,

A good choice [of General Staff ] is of . . . immense consequence. . . . [They] ought to be men of the most respectable character, and of first-rate abilities; because, from the nature of their respective offices, and from their being always about the Commander-in-Chief, who is obliged to entrust many things to them confidentially, scarcely any movement can take place without their knowledge. . . . Besides possessing the qualifications just mentioned, they ought to have those of Integrity and prudence in an eminent degree, that entire confidence might be reposed in them. Without these, and their being on good terms with the Commanding General, his measures, if not designedly thwarted, may be so embarrassed as to make them move heavily on.34

The point of all of this is that Washington believed that a leader’s actions and integrity must illustrate his own commitment to his commands to his followers. A successful leader must lead by example. Washington could not have called on his men to be such authentic Christians, if he was not trying to be such a Christian as well. So it would seem that Bird Wilson did not search thoroughly enough for the Christianity of Washington in his writings. Furthermore, if you read the text of the prayers in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer that Washington and his fellow worshipers read regularly in the weekly worship services, you would repeatedly see the exaltation of Jesus Christ.

CONCLUSION

We believe that modern skeptics have read into Washington their own unbelief. Just as many Christians have read too much piety into the man, we believe modern skeptics have read too much skepticism into George Washington. The skeptics, however, are on even shakier ground than the pietists that Professor Boller ridicules for their uncritical reliance on unsubstantiated anecdotes and stories that turn Washington into a paragon of devotional piety. The skeptics have remade Washington into their own unbelieving image—even though:

• He was clearly and deeply biblically literate. As we will see from his private and public writings, his pen inks scriptural phrases and concepts from all parts of the Bible.

• He was a committed churchman, attending regularly when it was convenient and inconvenient; he not only attended service, but he diligently served the church, primarily in his youth, as a lay leader; throughout his life, he generously donated money and material goods for the well-being of the church.

• He was generally very quiet about anything pertaining to himself, including his faith, yet he was always concerned to respect the faith of others, attempting to practice his Christian faith privately, even while he at times openly affirmed his Christian beliefs in public. There are numerous accounts from family and military associates—too numerous to be dismissed—of people coming across Washington in earnest, private prayer.

• He repeatedly encouraged piety, public and private; he insisted on chaplains for the military and legislature; he often promoted “religion and morality” and recognized these as essential for our national happiness, and even called on the nation’s leaders to follow Christ’s example.

• He turned away from the opportunity to become a king, even though a lesser man would have seized such power; he had not fought the king in order to become a new king, even though men wanted to make him that after he won the War. Indeed, Washington is a striking model of what Christians have called a servant-statesman.

These and many other indicators show that the scholars of recent years have been misreading George Washington and ignoring the spiritual realities of our founding father. By so doing, they have presented a very truncated picture of “his Excellency.”

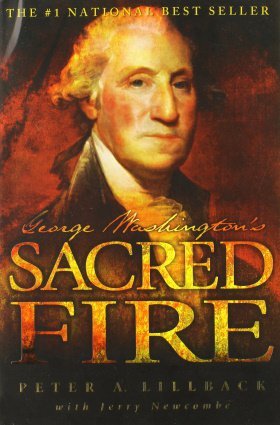

George Washington’s Sacred Fire intends to convince you that when all the available evidence is considered, the only viable conclusion is that George Washington was a Christian and not a Deist. What enflamed Washington’s passion and stirred his heart was that which was sacred to his soul—his utter dependence on the hand of Divine Providence.

His passion is important for us as well. Where a nation began determines its destiny. Is the Judeo-Christian heritage of America a reality or an interloper aimed at suppressing the secularism of the founders? Or, is it the other way around? Are today’s secularists trying to recreate the faith of our founding father into the unbelief of a Deist in order to rid our nation of Washington’s holy flame of faith? Was it a secular flame or a “sacred fire” that Washington ignited to light the lamp for America’s future? If we look carefully at Washington’s words, it is clear that it was a “sacred fire.” Throughout the rest of this book, we will continue carefully to consider his words. And as we do, we believe that they will fuel the “sacred fire of liberty” and continue to illumine the path to America’s future.

TWO

Deism Defined:

Shades of Meaning, Shading the Truth

“The man must be bad indeed who can look upon the events of the American Revolution without feeling the warmest gratitude towards the great Author of the Universe whose divine interposition was so frequently manifested in our behalf.”

George Washington 1789

1

“The hand of Providence has been so conspicuous in all this, that he must be worse than an infidel that lacks faith”

George Washington, 1778

2

Deism: n. [Fr. Deisme; Sp. Deismo; It. Id.; from L. deus, [God]. The doctrine or creed of a Deist; the belief or system of religious opinions of those who acknowledge the existence of one God, but deny revelation: or deism is the belief in natural religion only, or those truths, in doctrine and practice, which man is to discover by the light of reason, independent and exclusive of any revelation from God. Hence deism implies infidelity or a disbelief in the divine origin of the scriptures.

Deist: n. [Fr. Deiste; It. Deista.] One who believes in the existence of a God, but denies revealed religion; one who professes no form of religion, but follows the light of nature and reason, as his only guides in doctrine and practice; a freethinker. Noah Webster, 1828 Dictionary of the American English Language3

Before we begin our study, we should define our terms. A Deist is one who believes that there is a God, but He is far removed from the daily affairs of men. God made the world and then left it to run on its own. The Deist’s God does not take an active interest in the affairs of men. He is not a prayer-answering God. Praying to Him has no value. Deism is in some ways the natural outworking of exalting reason alone—that is, human reason apart from divine revelation.

The meaning of Deism has changed through the years. What Deism meant in Washington’s day and what it meant later is an important point in terms of understanding the religious milieu of George Washington. Because of these shades of meaning, there has been scholarly confusion over the use of the word “Deism.” Deism, in general, whether in Washington’s day or after, has not believed what the New Testament declares: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God and the Word was God….And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us…” (John 1:1, 14, NASB). In other words, a Deist, most decidedly, did not accept the Christian claim of the incarnation—that is, that God entered time and space to reveal himself to humanity through his son Jesus Christ.

Scholars identify our founders with secularism or Deism. Does this mean that they did not believe in God’s providential actions in American history? Or is it possible that in this period of history there was an earlier form of Deism that still prayed and believed in Providence, but denied that the Bible was the revelation of God? The difference between the two can be described by what we will call “hard Deism” and “soft Deism.”

Hard Deists rejected more elements of Christianity than soft Deists. A hard Deist not only denied that God had revealed himself in scripture, but he also denied that God acts in history, which is usually described by the word “Providence.” Thomas Paine, the best representative of what we are calling hard Deism, in his Age of Reason, rejected the idea of Providence, calling it one of the five deities of Christian mythology.4 Hard Deists also typically rejected a belief in God’s hearing and answering prayer. The movement from the original soft Deism to the fully developed hard Deism is reflected in Crane Brinton’s comment in The Shaping of Modern Thought: “One of the most remarkable examples of the survival of religious forms is found when professed Deists indulge in prayer, as they occasionally did. After all, the whole point about the Deist’s clockmaker God is that he has set the universe in motion, according to natural law and has thereupon left it to its own devices. Prayer to such a god would seem peculiarly inefficacious.”5 This is clearly the conclusion that Thomas Paine reached in the Age of Reason.6 In other words, Deism means an absentee God.

Many consider Washington to have been a soft Deist. Supposedly, this would mean that Washington did not believe that God revealed himself in the Bible. It also means that he did not accept the Christian claims of Christ’s divine nature, nor of His atoning death for man’s sin and his resurrection from the dead, but that he may well have believed in prayer and Providence, in some sense. Further, while not even the strictest skeptic accuses Washington of being a hard Deist, there is a tendency to inappropriately compare Washington and Paine. Boller, for example, writes that both Washington and Paine used similar deistic names for God. Yet there was a deep divide between the two. The tension between Paine and Washington began over Paine’s book the Rights of Man.7 Before this, their friendship had been strong; Washington had loved Common Sense and loved Paine’s logical arguments that called for the American Revolution that he so ably put forth.8 But Paine’s criticism of Washington in the context of the Rights of Man is captured by Washington biographer Thomas Flexner: