Copyright © 2024 by J. Malcolm Garcia

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, by any means, including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Some of the chapters in this work were originally published in the Alaska Quarterly Review, Bull, Green Hills Literary Lantern, McSweeney’s, River Oak Review, War, Literature & the Arts, and ZYZZYVA.

Seven Stories Press

140 Watts Street

New York, NY 10013

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Garcia, J. Malcolm, 1957- author.

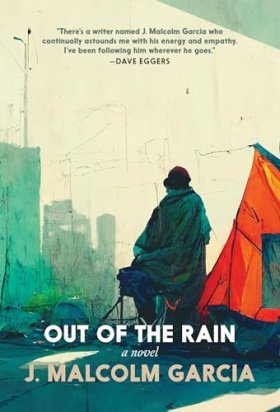

Title: Out of the rain : a novel / J. Malcolm Garcia.

Description: New York : Seven Stories Press, 2024.

Identifiers: LCCN 2023046742 | ISBN 9781644213865 (trade paperback) | ISBN 9781644213872 (ebook)

Subjects: LCGFT: Novels.

Classification: LCC PS3607.A7218335 O98 2024 | DDC 813/.6--dc23/eng/20231212

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023046742

College professors and high school and middle school teachers may order free examination copies of Seven Stories Press titles. Visit https://www.sevenstories.com/pg/resources-academics or email academic@sevenstories.com.

Printed in the United States of America

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

for Sandy Weiner

Tom

I’m standing at Golden Gate and Leavenworth across from Fresh Start. It’s a program that serves the homeless in the Tenderloin. I’m the director, I’m in charge, but not really. What happens on a given day more often ends up directing me than the other way around. We offer twenty-four-hour detox and a daytime drop-in center. In another building on Leavenworth we have a homeless shelter. I have four floor supervisors, six counselors, a benefits advocate, an outreach worker, and two support group facilitators. Homeless men and women also help out as volunteers. They mop the floors, check people in at the front desk, answer phones, serve snacks, and make coffee. In exchange, I guarantee them a shelter bed.

Glancing up at the second-floor window of my office, I see my boss, James McGraw, leaning over my desk. What’s he doing here? Squinting through the gray morning fog, I watch him open a cabinet and remove a file. I rub my face, look at the time on my phone. Eight o’clock. He never comes in this early, and he has never riffled through my files, at least that I know of. Sure, he’s the executive director. He can do what he wants, but I don’t like this. More than that, I know it can’t be good.

I open and close my eyes, open and close them again, and shake my head. My temples pound with the reverb of a hangover. I take a deep breath and try to shake it off knowing that’s not going to work. You knock off a six-pack of Budweiser the night before and this is what happens, I tell myself. Should’ve taken two or three Advil when I got up this morning. Could’ve used some coffee too. Rather have a beer to take the edge off, for real. Might have one for lunch then stop somewhere for a grilled cheese sandwich with onions and garlic to kill my breath. Learned that trick from Walter, a forty-something homeless alcoholic. I’ve put Walter in detox more than a few times. One day he came in slurring his words and swaying, and I noticed that I didn’t smell booze on his breath. It was godawful in every way, thick enough to cut with a knife, heavy with undefinable odor, but nothing I could discern as alcohol. I mentioned that to him and he told me in a rush of barely intelligible words about his grilled cheese sandwich concoction. He thought of it after our social worker got him a job interview at a temp agency. Walter had some time before the interview and started drinking. He knew he couldn’t risk smelling like Thunderbird wine. So he went to David’s Deli on Larkin Street and ordered a grilled cheese with a unique set of ingredients he thought would obscure the fact he’d been drinking. He winked at me, thought he was pretty clever. Then he asked for detox. When I saw him later, he never mentioned the interview, so I presume he didn’t get the job. Being barely able to stand probably didn’t score him any points, breath or no breath. He drank way too much for his sandwich trick to work. Lesson learned. One beer at lunch, I tell myself. One beer and a grilled cheese sandwich.

Moisture collects on my beard, the fog so dense it clings like an extra layer of clothes. A shiver rattles my spine. I expect the fog won’t lift until midday. Typical San Francisco winter. I should’ve called in sick with this hangover, then tried to persuade my girlfriend, Mary, to do the same and come over. She’s a paralegal at Welfare Mother’s United, an advocacy group for single moms. A few months ago, her boss asked me to speak to her staff about what we do at Fresh Start. I noticed Mary right off. She had curly black hair and a smile that pulled me in faster than a whirlpool does a drowning man.

Are you coming over? she asked me last night. I was on my third beer by then.

I want to, I said, but I’m tired. I think I’ll stay in.

There was a long pause before she said, OK.

I felt sort of bad. Then I drained my beer and got up for another one.

It had been a bad day. I fired one of my staff, a guy named Frank Harrison. When I hired him, Frank had just graduated from a forty-five-day alcoholism program and had moved out of a halfway house and into a hotel for recovering drunks on Ellis Street. Then he came in loaded one day for his shift and I told him to leave. Had he left, eventually we could have worked something out. I would’ve cut him a deal: You can keep your job if you stop drinking and attend at least one AA meeting a day, but he didn’t leave. He cussed me out and threw a vase of fake flowers at my head, clipping my left ear. A little more to the right and I would have had a full-on concussion. I can handle being cussed out; a broken head, not so much. I cut him loose. But I was generous. I mean, I’ve got a heart. If I fired him, I knew he wouldn’t be eligible for unemployment. However, if I called his termination a layoff, he would be. A layoff isn’t an employee’s fault. I had nothing against Frank. He just started drinking again. Most of my staff does. I drink, but I don’t act a fool at work. There’s a difference.

Frank didn’t act particularly appreciative. In fact, he didn’t say anything, I mean literally not a word. He just left. Like everything had gone according to plan, as if he had planned for this outcome. No job, no reason to stop drinking. I felt set up in a way. He didn’t need an excuse but I gave him one. And I guess he gave me one too, because I knew he’d be one more of my guys I’d see back on the street. It’s not my fault, but it weighs heavy. Or maybe like Frank, I just wanted to drink too. Whatever. I sure tied one on last night.

What’s going on, Tom Murray?

I turn to see Walter walking up behind me.

Morning, Walt. I was just thinking of you.

What about?

Nothing special.

He tugs a blue cloth cap down on his head; a storm of gray curls sprouts out around both of his ears. When he doesn’t wear the cap, he sports a toupee so black it looks like he shined it with shoe polish. The hairpiece slants increasingly askew as the day and his level of intoxication progress.

This morning, his hands shake as violently as my head is pounding. A rip stretches like a scar down a sleeve of his open brown corduroy jacket. He’s wearing a couple of sweaters punched with holes. The breeze carries the odor of his sweat-dampened clothes into my face. He has a bird-lidded look, as if he is still half asleep.

What’s going on, Tom Murray? he asks again.

Coming to work, same ol’ same ol’.