"I threatened to dismiss him and put the first mate in his place. I was angry, naturally."

"And what did the captain reply?"

"He made an absurd threat to put me in irons."

"What were your relations after that?"

"They were strained. We simply avoided each other."

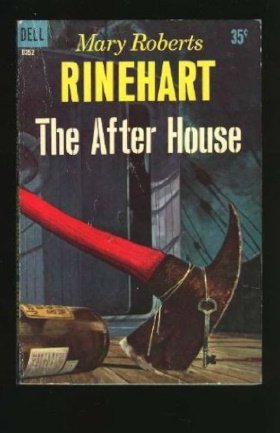

"Just a few more questions, Mr. Turner, and I shall not detain you. Do you carry a key to the emergency case in the forward house, the case that contained the axe?"

Like many of the questions, this was disputed hotly. It was finally allowed, and Turner admitted the key. Similar cases were carried on all the Turner boats, and he had such a key on his ring.

"Did you ever see the white object that terrified the crew?"

"Never. Sailors are particularly liable to such hysteria."

"During your delirium, did you ever see such a figure?"

"I do not recall any details of that part of my illness."

"Were you in favor of bringing the bodies back to port?"

"I—yes, certainly."

"Do you recall going on deck the morning after the murders were discovered?"

"Vaguely."

"What were the men doing at that time?"

"I believe—really, I do not like to repeat so often that I was ill that day."

"Have you any recollection of what you said to the men at that time?"

"None."

"Let me refresh your memory from the ship's log."

(Reading.) "'Mr. Turner insisted that the bodies be buried at sea, and, on the crew opposing this, retired to his cabin, announcing that he considered the attitude of the men a mutiny.'"

"I recall being angry at the men—not much else. My position was rational enough, however. It was midsummer, and we had a long voyage before us."

"I wish to read something else to you. The witness Leslie testified to sleeping in the storeroom, at the request of Mrs. Johns". (reading), "'giving as her reason a fear of something going wrong, as there was trouble between Mr. Turner and the captain.'"

Whatever question Mr. Goldstein had been framing, he was not permitted to use this part of the record. The log was admissible only as a record on the spot, made by a competent person and witnessed by all concerned, of the actual occurrences on the Ella. My record of Mrs. Johns's remark was ruled out; Turner was not on trial.

Turner, pale and shaking, left the stand at two o'clock that day, and I was recalled. My earlier testimony had merely established the finding of the bodies. I was now to have a bad two hours. I was an important witness, probably the most important. I had heard the scream that had revealed the tragedy, and had been in the main cabin of the after house only a moment or so after the murderer. I had found the bodies, Vail still living, and had been with the accused mate when he saw the captain prostrate at the foot of the forward companion.

All of this, aided by skillful questions, I told as exactly as possible. I told of the mate's strange manner on finding the bodies; I related, to a breathless quiet, the placing of the bodies in the jolly-boat; and the reading of the burial service over them; I told of the little boat that followed us, like some avenging spirit, carrying by day a small American flag, union down, and at night a white light. I told of having to increase the length of the towing-line as the heat grew greater, and of a fear I had that the rope would separate, or that the mysterious hand that was the author of the misfortunes would cut the line.

I told of the long nights without sleep, while, with our few available men, we tried to work the Ella back to land; of guarding the after house; of a hundred false alarms that set our nerves quivering and our hearts leaping. And I made them feel, I think, the horror of a situation where each man suspected his neighbor, feared and loathed him, and yet stayed close by him because a known danger is better than an unknown horror.

The record of my examination is particularly faulty, McWhirter having allowed personal feeling to interfere with accuracy. Here and there in the margins of his notebook I find unflattering allusions to the prosecuting attorney; and after one question, an impeachment of my motives, to which Mac took violent exception, no answer at all is recorded, and in a furious scrawl is written: "The little whippersnapper! Leslie could smash him between his thumb and finger!"

I found another curious record—a leaf, torn out of the book, and evidently designed to be sent to me, but failing its destination, was as follows: "For Heaven's sake, don't look at the girl so much! The newspaper men are on."

But, to resume my examination. The first questions were not of particular interest. Then:

"Did the prisoner know you had moved to the after house?"

"I do not know. The forecastle hands knew."

"Tell what you know of the quarrel on July 31 between Captain Richardson and the prisoner."

"I saw it from a deck window." I described it in detail.

"Why did you move to the after house?"

"At the request of Mrs. Johns. She said she was nervous."

"What reason did she give?"

"That Mr. Turner was in a dangerous mood; he had quarreled with the captain and was quarreling with Mr. Vail."

"Did you know the arrangement of rooms in the after house? How the people slept?"

"In a general way."