"I am sure of that. You are certain you are comfortable there?"

"Perfectly."

"Then—good-night. And thank you."

Unexpectedly she put out her hand, and I took it. It was the first time I had touched her, and it went to my head. I bent over her slim cold fingers and kissed them. She drew her breath in sharply in surprise, but as I dropped her hand our eyes met.

"You should not have done that," she said coolly. "I am sorry."

She left me utterly wretched. What a boor she must have thought me, to misconstrue her simple act of kindness! I loathed myself with a hatred that sent me groveling to my blanket in the pantry, and that kept me, once there, awake through all the early part of the summer night.

I wakened with a sense of oppression, of smothering heat. I had struggled slowly back to consciousness, to realize that the door of the pantry was closed, and that I was stewing in the moist heat of the August night. I got up, clad in my shirt and trousers, and felt my way to the door.

The storeroom and pantry of the after house had been built in during the rehabilitation of the boat, and consisted of a short passageway, with drawers for linens on either side, and beyond, lighted by a porthole, the small supply room in which I had been sleeping.

Along this passageway; then, I groped my way to the door at the end, opening into the main cabin near the chart-room door and across from Mrs. Turner's room. This door I had been in the habit of leaving open, for two purposes—ventilation, and in case I might be, as Mrs. Johns had feared, required in the night.

The door was locked on the outside.

I was a moment or two in grasping the fact. I shook it carefully to see if it had merely caught, and then, incredulous, I put my weight to it. It refused to yield. The silence outside was absolute.

I felt my way back to the window. It was open, but was barred with iron, and, even without that, too small for my shoulders. I listened for the mate. It was still dark, and so not yet time for the watch to change. Singleton would be on duty, and he rarely came aft. There was no sound of footsteps.

I lit a match and examined the lock. It was a simple one, and as my idea now was to free myself without raising an alarm, I decided to unscrew it with my pocket-knife. I was still confused, but inclined to consider my imprisonment a jest, perhaps on the part of Charlie Jones, who tempered his religious fervor with a fondness for practical joking.

I accordingly knelt in front of the lock and opened my knife. I was in darkness and working by touch. I had extracted one screw, and, with a growing sense of satisfaction, was putting it in my pocket before loosening a second, when a board on which I knelt moved under my knee, lifted, as if the other end, beyond the door, had been stepped on. There was no sound, no creak. Merely that ominous lifting under my knee. There was some one just beyond the door.

A moment later the pressure was released. With a growing horror of I know not what, I set to work at the second screw, trying to be noiseless, but with hands shaking with excitement. The screw fell out into my palm. In my haste I dropped my knife, and had to grope for it on the floor. It was then that a woman screamed—a low, sobbing cry, broken off almost before it began. I had got my knife by that time, and in desperation I threw myself against the door. It gave way, and I fell full length on the main cabin floor. I was still in darkness. The silence in the cabin was absolute. I could hear the steersman beyond the chart-room scratching a match.

As I got up, six bells struck. It was three o'clock.

Vail's room was next to the pantry, and forward. I felt my way to it, and rapped.

"Vail," I called. "Vail!"

His door was open an inch or so. I went in and felt my way to his bunk. I could hear him breathing, a stertorous respiration like that of sleep, and yet unlike. The moment I touched him, the sound ceased, and did not commence again. I struck a match and bent over him.

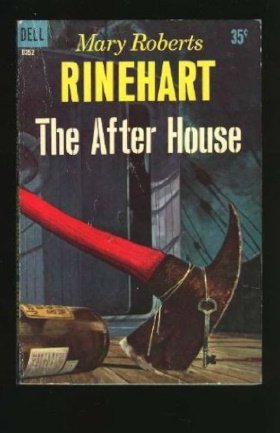

He had been almost cut to pieces with an axe.

CHAPTER VI

IN THE AFTER HOUSE

The match burnt out, and I dropped it. I remember mechanically extinguishing the glowing end with my heel, and then straightening to such a sense of horror as I have never felt before or since. I groped for the door; I wanted air, space, the freedom from lurking death of the open deck.

I had been sleeping with my revolver beside me on the pantry floor. Somehow or other I got back there and found it. I made an attempt to find the switch for the cabin lights, and, failing, revolver in hand, I ran into the chart-room and up the after companionway. Charlie Jones was at the wheel, and by the light of a lantern I saw that he was bending to the right, peering in at the chartroom window. He turned when he heard me.

"What's wrong?" he asked. "I heard a yell a minute ago. Turner on the rampage?" He saw my revolver then, and, letting go the wheel, threw up both his hands. "Turn that gun away, you fool!"

I could hardly speak. I lowered the revolver and gasped: "Call the captain! Vail's been murdered!

"Good God!" he said. "Who did it?" He had taken the wheel again, and was bringing the ship back to her course. I was turning sick and dizzy, and I clutched at the railing of the companionway.

"I don't know. Where's the captain?"

"The mate's around." He raised his voice. "Mr. Singleton!" he called.

There was no time to lose, I felt. My nausea had left me. I ran forward to where I could dimly see Singleton looking in my direction.

"Singleton! Quick!" I called. "Bring your revolver."

He stopped and peered in my direction.

"Who is it?"

"Leslie. Come below, for God's sake!"

He came slowly toward me, and in a dozen words I told him what had happened. I saw then that he had been drinking. He reeled against me, and seemed at a loss to know what to do.

"Get your revolver," I said, "and wake the captain."

He disappeared into the forward house, to come back a moment later with a revolver. I had got a lantern in the mean time, and ran to the forward companionway which led into the main cabin. Singleton followed me.

"Where's the captain?" I asked.

"I didn't call him," Singleton replied, and muttered something unintelligible under his breath.

Swinging the lantern ahead of me, I led the way down the companionway. Something lay huddled at the foot. I had to step over it to get down. Singleton stood above, on the steps. I stooped and held the lantern close, and we both saw that it was the captain, killed as Vail had been. He was fully dressed except for his coat, and as he lay on his back, his cap had been placed over his mutilated face.