‘Whites don’t understand that. They, got to have documents, deeds; papers that say this bit belongs to you, and that bit belongs to him. They don’t understand why an Indian drifts; no more than an Indian knows why a white man needs a house, and all that. My mother’s people, they’ll be gone into Mexico now. It’s warmer there, and the hunting is good. They’ll follow the buffalo and the wild horses. Take what they want and then come back in the spring to set up the rancherias for the summer. That’s why the whites call them drifters; worthless Indians.’

Backenhauser emptied the bottle. ‘And that’s why Dumfries will keep coming after us?’

‘Sure,’ said Azul. ‘I killed his son. Then I killed some of his men. I took something away from him. He won’t forgive me that. You neither. He’s got to find us and kill us so he can go on proving he’s the boss.’

There was a silence in the conversation. The piano started in afresh on the same old tune. Backenhauser sipped his whiskey and shook his head.

Then, ‘You can talk when you want.’

‘Yeah,’ said Azul.

‘You feel it, though,’ said the Englishman. ‘More than you show; right?’

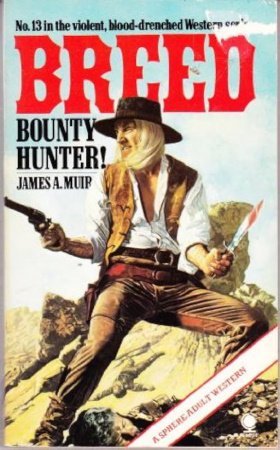

‘My father was white,’ said the half-breed, slowly. ‘My mother was Chiricahua. That gives me a different view. I guess I can see both sides. That’s maybe why these people’d cheer Dumfries on: there’s not many like a ’breed.’

‘I guess.’ Backenhauser yawned. ‘I’m about ready for bed. You got a room yet?’

‘No.’ Azul draped his saddlebags over his shoulder. ‘I’ll get a place in the hotel.’

They stood up as the Negro began the tune again; As they passed the bar, the keeper smiled at the half-breed.

‘You like the way Sam plays?’

Azul shook his head. ‘I wish Sam’d quit playing that tune again.’

Chapter Seven

THE LORDSBURG STAGE came in half a day ahead of schedule, and Backenhauser got ready to climb on board. He had spent his time in Placeras sketching the town, taking care that Azul was nearby whenever he chose a human subject. He had also devoted hours to sketching the half-breed, explaining that when he found himself a studio he would turn the drawings into a full-size painting. Azul was amused and vaguely flattered: the only time his likeness had been drawn before was on a wanted poster.

He accompanied Backenhauser to the depot, watching as the artist’s baggage was stowed in the concord’s tarpaulin-covered boot. Then the manager clapped his hands and yelled for silence.

‘Sumthin’ I gotta tell you folks,’ He coughed, raising his voice. ‘I got word from the Army there’s a bunch o’ bronco Apaches runnin’ loose in the Paradise Valley. Army says they got patrols out, but they’re warnin’ folks that the broncos been hittin’ the coaches. You best decide if you want to take this one, or wait over.’

A man in a drummer’s suit, clutching a portmanteau to his chest, gulped and said, ‘Oh my God!’

Backenhauser laughed and murmured, ‘Sounds like I’m jumping out of the frying pan into the fire.’

‘You got a choice,’ grunted Azul. ‘You can stay here an’ hope Dumfries don’t catch up or take the stage an’ hope the broncos don’t hit it.’

‘What is a bronco?’ asked Backenhauser. ‘I thought that was one of your words for a horse.’

‘It is,’ said the half-breed. ‘But it also means a wild Apache. Usually, it’s a bunch of young men decided to go out fighting against the council of the elders.’

‘What’s the Army doing?’ asked a woman with a hawkish nose shadowed by her poke bonnet. ‘Ain’t they sendin’ an escort?’

‘Don’t have the men,’ replied the depot manager, shrugging. ‘I guess they’re hopin’ the patrols will keep the broncos away. Could be you’ll pick up a patrol in the valley, but I can’t make no promises.’

‘How many guards are you providing?’ demanded a thin man in a black frock coat. ‘Can’t you hire outriders?’ The manager shrugged again. ‘You just paid fer a seat on the coach, mister. Not a guard of honor. You’ll have a driver an’ a shotgun rider, that’s all.’

The thin man brushed his pencil mustache. ‘It seems that you might well extend your services beyond the simple realms of providing travel facilities sir. In troubled times one expects some guarantee of safety from the mentors of the transport system.’

‘I ain’t sure I understood all o’ that.’ The manager’s face creased up in a frown. ‘But if I did, then I’m sayin’ no. Sorry, but I can’t.’

He mopped his face with a dirty handkerchief, then: ‘You got three choices, folks. You can take the stage, an’ we’ll do our damnedest to get you through safe to Lordsburg. Or you can wait over an’ take another coach when the Army says things have quieted down. Or I can refund yore money an’ you make your own arrangements.’

Backenhauser turned to Azul. ‘What do you think I should do?’

‘Take the stage.’ Azul shrugged. ‘Hell! I guess Lordsburg’s as good a place as any. I’ll ride herd on you some more.’ The Englishman grinned and stepped towards the depot manager, holding up his ticket.

‘I’ll chance it.’

‘Fine.’ The manager stamped the ticket and looked around the room. ‘Anyone else?’

Only two people followed the artist’s example. The frock coated man and the drummer; the remaining passengers sidled away.

‘Don’t tell no one I’ll be trailing you,’ murmured Azul. ‘That way Dumfries won’t know which of us to follow.’

Backenhauser nodded and climbed into the concord. He shook hands with Azul and bade the half-breed a noisy farewell. Azul fetched his horse from the stable and rode away to the south.

Two miles clear of Placeras he turned the

gray’s head to the west and heeled the big pony up to a fast canter

that headed them along a line that would bisect the concord’s

route.

Mike Stotter took his team out at a fast lick. It had long been his theory that a show of speed at the beginning of a run impressed the passengers. It also got them swiftly accustomed to the rolling gait of the stage and allayed any complaints about time wasting.

Stotter had been driving the Lordsburg run since he was twenty. He had been a teamster during the Civil War, emerging from the conflict at the age of nineteen with two commendations for bravery in the face of the enemy and the proud memory of a handshake from Ulysses S. Grant himself. He had never gone back home to Kansas, drifting instead to the Southwest where, as the stage routes opened up again after the war, he found employment as a driver. He had a wife in Lordsburg and a Mexican girl in Placeras. And along the way, there was a lady in Gilman who dropped everything when she heard the coach coming in.

For the last five years Stotter had ridden with a shotgun guard called Dave Weisskopf.

Weisskopf was a natural partner, his talent with shotgun or rifle complementing Stotter’s skill as a driver. He was from Illinois, his parents second generation immigrants from Austria, and like Stotter, he had served honorably in the Civil War. He was taller than his friend, with wavy hair where Stotter’s was curly; quiet where Stotter was a talker, with the phlegmatic calm of purpose inherent in his Austrian background. Mainly, he was the best shotgun rider Stotter had known.