‘This cut is the deepest,’ murmured the old man, his bird-bright eyes boring into the Mimbreño’s. ‘For you have invited Azul into your camp and taken food with him. You agreed to talk. Like a reasonable man, not a savage animal. If you go back on all that, then you will lose your honor.’

Knife-With-Two-Sides laughed, but the sound was hollow and his eyes could not stay fixed on the old man’s stare. He wiped his severed nose again, and touched the scar running down his cheek.

‘You talk to me of honor, brujo? The honor I have is in fighting the men who try to take away the land of my people. That is why we live here, like wolves. Without women, because they would slow us down. That is why we die fighting the pinda-lick-oyi.’

‘Azul is not your enemy,’ said Cuervo softly, though his voice cut through the smoky silence like the knife of the wind’s breath. ‘Half his blood is white, but his father was a man who knew the people of Apacheria. A man who loved them and fought for them. A man who died for them. Azul is more Chiricahua than he is white.’

‘I could still kill him,’ grunted the Mimbreño.

‘And kill your honor,’ said the old man. ‘And afterwards, I would go away and spread word of what you did, so that when men spoke the name of Knife-With-Two-Sides they would spit, and there would never be a child given that name.’

The bronco grunted, ducking his head so that his eyes were hidden behind his hair. Cuervo looked at Azul, motioning for him to speak.

‘I will give you one thousand American dollars,’ said the half-breed. ‘I am not afraid of you, but I do not want to fight you. I know from the past that Cuervo speaks truth and sense. One thousand dollars will buy many guns.’ Knife-With-Two-Sides clutched his Winchester, rocking gently back and forth. Then he raised his head.

‘For that I will give you the pinda-lick-oyi. After he has made me the medicine picture.’

‘So it is,’ said Azul. ‘And Cuervo is witness.’

The old brujo nodded, and the bronco chief stood up, walking out from the cave into the brightening daylight.

‘What happened?’ asked Backenhauser. ‘What were you talking about?’

‘I just bought you,’ grunted Azul. ‘But you have to draw him first.’

‘How much?’ The artist moved up to the fire. ‘What’m I worth?’

‘One thousand dollars,’ said the half-breed. ‘And the picture.’

The Englishman whistled softly: ‘I never sold a painting for that much before. That’s a lot of money.’

Azul shrugged. ‘It was that or chance a fight.’

‘You are lucky,’ said Cuervo, ‘to have a friend like Azul.’

‘Yes.’ Backenhauser nodded. ‘I guess I am. He’s real generous.’

‘It’s only money,’ murmured the half-breed. ‘And I always heard good artists cost a lot.’

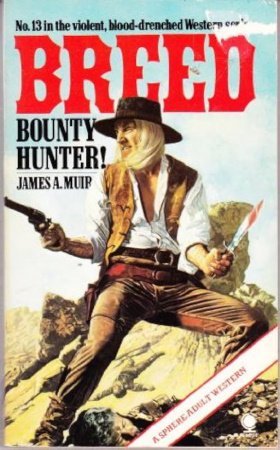

Chapter Nine

FRITZ BAUM AND Amos Dumfries reached Placeras a week after the attack on the stage.

The rancher had wanted to bring some of his men along, but the bounty hunter had vetoed the idea, unwilling to risk the vengeful Dumfries organizing an impromptu hanging. In his own curious way, Baum felt a sense of honor. By now he had heard enough about the man called Matthew Gunn that he held a picture of the man in his mind. Not a visual image, but an idea of a man riding his own trail, living his own life no matter what the odds. He felt a grudging respect; almost a kinship with his quarry.

And he was determined to fulfill the terms of his contract: to find Breed and take him back to the mysterious man in Cinqua.

By the time they reached Placeros the Army had found the wrecked stage and brought the bodies in. Passengers and crew were all buried in the little graveyard outside of town, and what few personal effects had been recovered were sent east to the line’s head office for subsequent return to any relatives.

The two men checked the graveyard. There were four markers, Stotter’s and Weisskopf’s bought by the company and inscribed with suitable legends. Stotter’s read: Michael Stotter. A fine driver and a brave man. Mourned by all who knew him. There were three pots of flowers on the grave, and in a small shack on the outskirts of town a Mexican girl was nursing a black eye and wondering what the new driver would look like. Weisskopf s marker just had a bunch of dying blooms below the words, David Weisskopf, a good man who is missed by all his friends.

The other two just carried names that had been supplied by the depot manager and paid for by the company. They were very simple, made of the cheapest stone available; tokens of the stage line’s responsibility.

There were no more graves.

Baum and Dumfries went back to the depot.

‘All I know is the little feller got on the stage. That’s all, mister. He was the first on. Seemed real anxious to go.’

Dumfries flattened a five-dollar bill carefully on the counter. ‘What about his friend? Tall man, with long blond hair.’

‘The half-breed?’ The depot manager shrugged. ‘He lit out afore the stage. Never bought no ticket. Best check with Andy, over to the stable.’

Dumfries and Baum went over to the stable.

‘Sure,’ said Andy, spitting a long plume of liquid tobacco over the straw. ‘I remember him. Big feller with mean eyes. Figgered him for a ’breed right from the start. Had good money, though. An’ a nice pony. Big gray stallion with Arab blood. Took it out a while afore the stage left. Don’t know where he was headed, though. I seen him in the Silver Dollar, drinkin’ with the little guy, so maybe Ned might know.’

Ned shook his head and scratched at a nail where the varnish had come loose.

‘I just serve drinks, friend.’ His eyes fluttered over Baum’s muscular frame and the German blushed. ‘I don’t ask too many questions. If you know what I mean.’

Dumfries stretched another five-dollar bill between his fingers.

‘But you hear things, don’t you?’

‘Oh sure.’ Ned took the bill. ‘I even heard them talk about going to Lordsburg, but I guess you know that. I mean, they wouldn’t have taken the stage otherwise, would they?’

‘Whiskey,’ rasped Baum. ‘An’ wash the glasses.’