“It might slip into a delusion that it had already taken one of the courses of action.”

I nodded happily. “I didn’t kill her. I decided I must; I got up, got dressed—and the next thing I knew I was outside, wandering, very confused. I got my money—and I understand now, with superempathy, how I can win anyone’s prize contest—and I went looking for a head-shrinker. I found a good one.”

“Thanks,” he said dazedly. He looked at me with a strangeness in his eyes. “And now that you know, what’s solved? What are you going to do?”

“Go back home,” I said happily. “Reactivate the superorganism, exercise it secretly in ways that won’t make Miss Kew unhappy, and we’ll stay with her as long as we know it pleases her. And we’ll please her. She’ll be happy in ways she’s never dreamed about until now. She rates it, bless her strait-laced, hungry heart.”

“And she can’t kill your—gestalt organism?”

“Not a chance. Not now.”

“How do you know it isn’t dead already?”

“How?” I echoed. “How does your head know your arm works?”

He wet his lips. “You’re going home to make a spinster happy. And after that?”

I shrugged. “After that?” I mocked. “Did the Peking man look at Homo Sap walking erect and say, ‘What will he do after that?’ We’ll live, that’s all, like a man, like a tree, like anything else that lives. We’ll feed and grow and experiment and breed. We’ll defend ourselves.” I spread my hands. “We’ll just do what comes naturally.”

“But what can you do?”

“What can an electric motor do? It depends on where we apply ourselves.”

Stern was very pale. “But you’re the only such organism…”

“Are we? I don’t know. I don’t think so. I’ve told you the parts have been around for ages—the telepaths, the poltergeists. What was lacking was the ones to organize, to be heads to the scattered bodies. Lone was one, I’m one; there must be more. We’ll find out as we mature.”

“You—aren’t mature yet?”

“Lord, no!” I laughed. “We’re an infant. We’re the equivalent of about a three-year-old child. So you see, there it is again, and this time I’m not afraid of it; Baby is three.” I looked at my hands. “Baby is three,” I said again, because the realization tasted good. “And when this particular group-baby is five, it might want to be a fireman. At eight, maybe a cowboy or maybe an FBI man. And when it grows up, maybe it’ll build a city, or perhaps it’ll be President.”

“Oh, God!” he said. “God!”

I looked down at him. “You’re afraid,” I said. “You’re afraid of Homo Gestalt.”

He made a wonderful effort and smiled. “That’s bastard terminology.”

“We’re a bastard breed,” I said. I pointed. “Sit over there.”

He crossed the quiet room and sat at the desk. I leaned close to him and he went to sleep with his eyes open. I straightened up and looked around the room. Then I got the thermos flask and filled it and put it on the desk. I fixed the corner of the rug and put a clean towel at the head of the couch. I went to the side of the desk and opened it and looked at the tape recorder.

Like reaching out a hand, I got Beanie. She stood by the desk, wide-eyed.

“Look here,” I told her. “Look good, now. What I want to do is erase all this tape. Go ask Baby how.”

She blinked at me and sort of shook herself, and then leaned over the recorder. She was there—and gone—and back, just like that. She pushed past me and turned two knobs, moved a pointer until it clicked twice. The tape raced backward past the head swiftly, whining.

“All right,” I said, “beat it.”

She vanished.

I got my jacket and went to the door. Stern was still sitting at the desk, staring.

“A good head-shrinker,” I murmured. I felt fine.

Outside I waited, then turned and went back in again.

Stern looked up at me. “Sit over there, Sonny.”

“Gee,” I said. “Sorry, sir. I got in the wrong office.”

“That’s all right,” he said.

I went out and closed the door. All the way down to the store to buy Miss Kew some flowers, I was grinning about how he’d account for the loss of an afternoon and the gain of a thousand bucks.

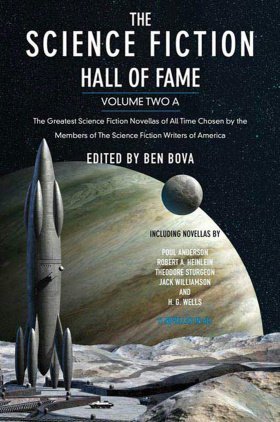

THE TIME MACHINE

by H. G. Wells

by H. G. Wells

The Time Traveller (for so it will be convenient to speak of him) was expounding a recondite matter to us. His grey eyes shone and twinkled, and his usually pale face was flushed and animated. The fire burned brightly, and the soft radiance of the incandescent lights in the lilies of silver caught the bubbles that flashed and passed in our glasses. Our chairs, being his patents, embraced and caressed us rather than submitted to be sat upon, and there was that luxurious after-dinner atmosphere when thought runs gracefully free of the trammels of precision. And he put it to us in this way—marking the points with a lean forefinger—as we sat and lazily admired his earnestness over this new paradox (as we thought it) and his fecundity.

“You must follow me carefully. I shall have to controvert one or two ideas that are almost universally accepted. The geometry, for instance, they taught you at school is founded on a misconception.”

“Is not that rather a large thing to expect us to begin upon?” said Filby, an argumentative person with red hair.

“I do not mean to ask you to accept anything without reasonable ground for it. You will soon admit as much as I need from you. You know of course that a mathematical line, a line of thickness nil, has no real existence. They taught you that? Neither has a mathematical plane. These things are mere abstractions.”

“That is all right,” said the Psychologist.