“I’ll have a soda. Any kind of cola is fine, so long as it has caffeine and refined white sugar.”

“With ice?”

“If you don’t mind.”

“Not at all.” He headed for a tall, glass-faced refrigerator. “Please don’t make a dash for the door. I’m a very good shot, and if you’re lying on the floor twisting in pain, you won’t enjoy your soda as much.” He winked at Ross Ed. “Don’t worry, son. I’ll take it out of your change.”

Instead of replying, Ross yawned helplessly. Returning with the cold can, which he passed to a grateful if wary Caroline, the owner regarded his heavy set guest.

“You look all done in, son. When’s the last time you had a decent sleep?”

“Not that long ago.” Unable to stop himself, he yawned again. Instinctively. Caroline mimicked him. “It’s just that my system’s kind of out of whack. I’ve been driving at night and sleeping during the day.

Walter nodded. “I guess we can fix that.” He indicated a rear door. “We’ve goi a couple of bunks in back, for visiting friends. Why don’t you go lie down?”

Too tired and confused to argue, Ross decided he might as well comply. After a decent nap he’d try to think of something. It would also be easier to come up with a solution to their present predicament if he had some idea as to just what the hell this charming country couple was up to. But as he escorted them toward the back room, Walter simply grinned and offered vague promises of incipient revelation.

“You’re sure you’re not going to call the police while we’re asleep?” Gingerly, Ross tested the springs on the bunk. They creaked, but held.

“Now, wouldn’t that be stupid? They’d have no conception of what you’ve found, no clue as to its import. On the other hand, Martha and I do. You’ll see. You’ll thank yourselves that you stumbled in on us.” He gestured with the pistol. “Sorry about the gun, but you’re a big fella and I didn’t feel like taking chances.” He backed toward the doorway. “We’ll call you if we need you.”

The door shut behind him. Unsurprisingly, the action concluded with a distinctive click as a lock was slipped home.

“What do they want with Jed?” He lay down on the bunk and stared at the ceiling. “I hope they don’t do anything stupid, like trying to pry him out of his suit.”

“Well, if they do, we should be pretty safe in here.” Sitting on the other bunk, she rapped her knuckles on the all-too-solid wall. “What’s it capable of, anyway?”

“I try hard not to think about it.” He rolled over to face her. After the jouncing, spine-jarring ride through the mountains, the bunk felt like his grandmother’s feather bed.

Shortly thereafter, he wasn’t feeling much of anything at all.

ELEVEN

It was past noon when he finally woke. If not completely relaxed and at ease, his body at least felt like it was back on a normal daytime schedule. In fact, he felt better than he had at any time since his hasty departure from El Paso.

The sole abnormality consisted of a heavy weight pressed up against him. Looking down, he saw that Caroline had dragged the other bunk over next to his and had snuggled as close as was possible. He tried to rise quietly, a procedure which for Ross Ed Hager was somewhat akin to trying to drive a dyspeptic steer up a loading chute without making any noise. She blinked, stretched, smiled, and then impulsively kissed him full on the mouth. He flinched slightly before relaxing, leaving it to her to finally pull away.

“What was that for?”

Rolling back onto her bunk, she straightened her hair and grinned mischievously. “Sorry. I thought you were my first husband.”

“The hell you did. You were wide-awake.”

“So I lied.” She sat up and yawned deliciously. “What are you going to do about it? Punish me?”

“That’s right. I’m going to make you do that again.” And he was about to when a gentle knock on the door interrupted them. He found himself saying automatically, “Come in,” even as he realized that as virtual prisoners, the knock signified the granting of still another unexpected courtesy. It didn’t make any sense. If their captors were a music genre he’d have to call them Cutthroat Country. He felt like they’d been captured by the Mayberry Militia movement. It was all very disconcerting.

It was the owner’s wife, all muffin smiles and bucolic vibes. “Good morning! Or I guess I should say, good afternoon. You two slept well.”

Uncertain whether her intent was to feed them, shoot them, or recruit them into the local quilting bee, Ross Ed rubbed sleep from his eyes. “Like we told your husband last night, we’ve been running on a nighttime schedule.” He blinked at her. “Where’s Jed?”

“Your little alien?” She reminded him of his ninth-grade English teacher, Mrs. DeWeese, who no matter the circumstances was forever smiling and chipper. Many’s the time he’d dreamed of strangling Mrs. DeWeese, slowly and with great pleasure.

However, unlike his teacher, who’d never employed anything more lethal than a yardstick, the owner’s wife cradled the threatening shape of the Mossburg lightly under one arm.

“Unless he’s suddenly come to life and learned how to jump-start a 1988 Ford van, I imagine he’s where you left him, on the floor next to the front seats. Don’t worry. Walter parked it in the shade. There’s a big carport out back we use for storing recreational vehicles.”

“So you operate this place as a garage, too?” Caroline had put her feet on the floor and turned to face the woman.

“Not officially, but Walter’s pretty handy and there’s always folks who pull in needing this or that minor problem fixed. Your van’ll be perfectly safe back there. Things are happening, you know. Our friends are starting to arrive.”

“Friends?” Ross was watching her carefully. What had they fallen into? “What sort of friends?”

“Members of our little organization. You’ll see.”

Caroline wasn’t sure she wanted to. “Unless you want to get yourselves involved in something over your heads, you’d better let us go now. U.S. Army Intelligence is after us.”

“Really? Oh, I doubt they’re after you. Your alien, now, that I can believe.” She laughed gaily. “My goodness, dear, do you think we worry about such things away up here? This is Arizona, young lady. We like to think of ourselves as more independent than folks back east. Maybe because we’re so much better armed.” She wagged a schoolmarmish finger at them. “You know old Ben Franklin’s saying: ‘A little target practice each day keeps one healthy, wealthy, and wise.’

“If these army people haven’t found you by now, then I don’t think they will for a while yet. Meantime we will be able to have a formal meeting of our group. Oh, there’s big things happening, there are!” She stepped aside. “Why don’t you come out and meet some of our friends?”

The captives exchanged a look. Together they rose from their respective bunks and followed the woman out into the store.

A couple of snack tables were piled high, and half a dozen people milled about, chatting and laughing. Ross Ed looked for but couldn’t find the husband. He did, however, notice that the blinds had been drawn on the windows and that the “Closed” sign had been put our.

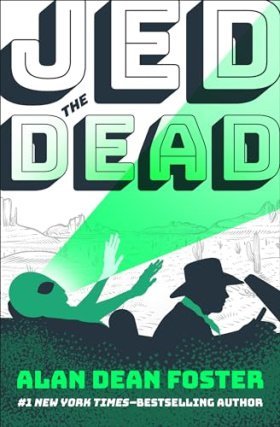

“Attention, attention please, everybody!” Conversation faded as all present turned to Martha’s direction. ‘his is the young man who found the alien we now know as ‘Jed.’”

Abruptly Ross found himself surrounded. His avid audience was a diverse lot, from wrinkled oldsters who made the store owners look like teens to bright-eyed couples in their twenties. Too bright-eyed. One perfectly tanned, prosperous-looking pair wore the same perpetually eager expression as his aunt Florene’s pedigreed cocker spaniels. As to the multitude of questions they threw at him, he was for the most part at a loss to come up with answers.