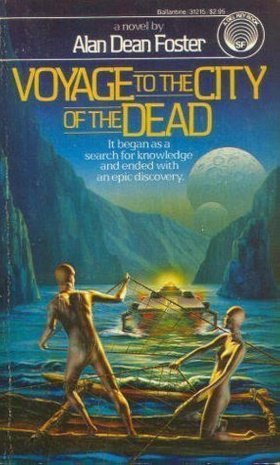

Voyage to the City of the Dead

A Humanx Commonwealth Novel

Alan Dean Foster

For Daniel, with love,

for when he gets older and starts traveling.

I

I

They didn’t call in the Guard because the intruder was already half dead. Still, they were upset.

Muttering angrily among themselves over the outrageous breach of protocol, the members of the Zanur looked to their leader for direction, but Najoke de-me-Halmur held his peace. It was up to the intruder to explain himself, and fast. Hands still hovered close to sheathed knives, although it was becoming apparent this was no assassination attempt—the intruder was too enfeebled to present a threat to anyone but himself. So Najoke stayed his hand as well as his lips. Seeing this, the other members of the Zanur calmed themselves.

Two unkempt servants attended the intruder, and they had their hands full keeping him on his feet. He was completely bald, as befitted his age, but more than age had been at work on that body recently. Pain was evident even in the movement of the eyes, and their owner was breathing as if he’d run a long ways, for all that two younger Mai supported him.

Several of the more impatient members of the Zanur started toward the stranger. De-me-Halmur stayed them with a wave of one slim, six-fingered hand. “Patience, my friends. Let us hear what this despoiler of etiquette has to say. Retribution can come later. We are no judges here.”

The leader’s words sparked the withered visitor’s attention. He shrugged off the helping hands of his servants, much as he continued to push away the clutching hand of death. Though unsteady and shaking, he stood straight and by himself. “Good members of the Zanur, I beg forgiveness for this intrusion on the affairs of state. When one has little time left, one has no time at all for protocol. I have much to tell you.”

De-Yarawut rose and pointed, hairless brows drawing together. “I know you. You reside in my district.”

The elderly speaker tried to bow to the side, as etiquette required, and the effort nearly sent him sprawling. His servants rushed to help but he gestured them back.

“I am flattered by your remembrance, Zanural de-Yarawut. I am Bril de-Panltatol. A humble trader who works Upriver.” The drama of the oldster’s intrusion, his unforgivable breach of tradition, was beginning to fade. And he was known. No surprises were here.

Legends sing of the wrongness of such thoughts.

“No excuse can be made for your interruption, de-Panltatol,” de-me-Halmur said. “You know the penalties.”

“Your most excessive indulgence, Moyt, but as I said and as you can see, little time is left to me.”

De-me-Halmur had not become ruler of a great city-state without the occasional ostentatious display of compassion. “You must have bribed efficiently to obtain this entrance, oldster. You are to be admired for that. Say what you have come to say.”

“Good members of the Zanur, I have for most of my life been a trader of fine woods and metals between our great city of Po Rabi and the Upriver. Hai, even as far as Kekkalong.” Kekkalong was a very long way Upriver, and many of the Zanurals had never journeyed beyond the boundaries of the city. They listened to the rover with a little more respect.

“I am a good citizen and work hard for my city. So I listen well to any tale or rumor that suggests the opportunity to increase my wealth.”

“As do we all,” Zanural de-Parinti commented. “Get on with it.”

“Among the many tales of the Upriver are those which speak of a dead place, home to spirits and ghosts and demons beyond counting, who guard such wealth as could not be counted in a thousand lifetimes by all the accountants of all the city-states that ring the Groalamasan itself.”

“A wonderful story, I’m sure,” another Zanural called from his council seat. “I too have heard such stories.”

“It is well known,” de-Panltatol continued, “that the nearer one travels to the source of such tales, the more vivid and impressive they become—or else they fade away entirely.

“This particular tale is told over and over again in a hundred towns and villages of the North. I have listened to it for more than fifty years. I resolved finally to pursue it to the last storyteller. Instead it drew me onward, pulling me ever farther north. Sometimes the tale smelled of truth, more often of village embroidery, but never did I lose track of it entirely.

“I went beyond maps and merchant trails, always up the Barshajagad, following the current of the Skar and in places abandoning it completely. I walked—I, Bril de-Panltatol—upon the surface of the frozen Guntali itself!”

Now the whispers of interest were submerged by ill-concealed laughter. The Guntali Plateau, from which arose all the great rivers of the world that drained into the single ocean that was the Groalamasan, was so high and cold and thin of air that no Mai could travel upon it. Yet the wrinkled old trader was laying claim to such a feat.

Like his fellow merchants and Zanural, de-me-Halmur refused to countenance the possibility, but neither did he laugh. He had not become Moyt of Po Rabi by dismissing the most elaborate absurdities without careful dissection. “Let this one continue proving himself the fool, but let him not be convicted until he has finished his story.”

“Up past even far Hochac I went,” de-Panltatol was breathing harder now, “and my journey was but beginning. I lost servants and companions until I was obliged to travel on my own, because none would go farther in my company. All believed me mad, you see. I nearly perished many times. The rumors and the river led me ever onward.”

“Onward to what?” another of the Zanural snorted derisively.

The oldster glanced sideways and seemed to draw strength from his scoffers. “To the source of all the tales and songs. To the land of the dead. To the part of the world where demons and monsters make their home. To the top of the world, good Zanural.”

This time the laughter could not be contained. It did not appear to discourage the old trader.

“I found the City of the Dead. I, Bril de-Panltatol! And I came away with a piece of it.” He frowned then, and wheezed painfully. “I don’t remember that time very well. My mind was numbed by all I had endured. How I stayed alive I don’t know, but I drove myself to make another boat. I made many boats, I think. It’s hard to remember. I disguised what I had brought away beneath a bale of Salp skins and brought it all the way Downriver, all the way back to my home, to Po Rabi.”