His temper was abating, but he glowered and said: “Yes, I do, and you’re not supposed to know anything about it.”

I shrugged. “Only what I read in the papers. I hear it’s been closed off, put off limits to everybody.”

“So have many others of the remote islands, come to that.”

“But not for the same reason. Ah...” The phone was ringing, and I took it and heard the operator say: “You call to Scotland coming through, Excellency.”

“Thank you.” I gave the phone to Fenrek and said: “Just introduce us, will you? I’m now going to solve your problem for you.”

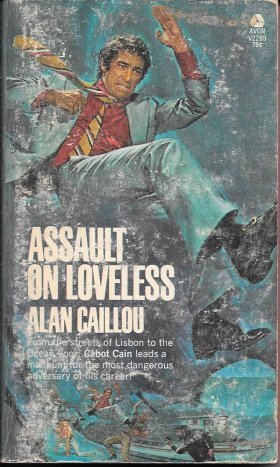

He sighed and took the phone, muttering under his breath. A nurse came in with a bowl of barley soup, and he took one look at it, sniffed it suspiciously, and snarled at her. She put it down on the table none the less, and he said into the phone: “McGivern? Fenrek. How are you?” He waited a moment then said: “As a matter of fact, I’m probably dying, and it’s nothing to do with the beautiful Portuguese women either. I want you to talk to an associate of mine, tell him what he wants to know...What? No, you can tell him anything. Here he is. Cabot Cain.”

He handed me the phone, took up the bowl of soup, sniffed it again, and put it back on the table. He snuggled closer under the bedclothes as Astrid tried to feed him.

I said: “Cabot Cain, Superintendent, how do you do? You remember that epidemic in the Farne Islands that killed off eight or nine of the islanders?”

His burr was strong, his voice ripe: “Aye, I do that, Mr. Cain.”

“The truck driver who died, a man named Alexander Stewart. Do you know anything about him?”

“Aye. What was it you wanted to know?”

“Was he a local man?”

“Aye, he was that. From St. Agnes.”

“And just before he died, say a few days before, did you ever find out if he’d been away? If he’d made a trip anywhere?”

“Aye. As a matter of routine, we investigated thoroughly, but we never found out where he’d been. He’d been away from St. Agnes for five or six days. But the Farne Islands, ye ken, are no Scottish, they’re British, and we don’t get the cooperation from them we might like to have. They’re Sassenachs there.” He sounded as though that explained everything, and when he said “British” there were half a dozen Rs in the middle of it.

I said: “In six days, he could have gone to Gruinard and spent a day or two there, couldn’t he?”

The heavily-accented voice was suddenly very cautious, “Aye, he could that, I suppose.”

“And what is it precisely that they were manufacturing on Gruinard, Superintendent?”

There was a long pause. I saw that Fenrek was watching me, suddenly very interested. The Superintendent said at last, very ponderously: “The Island of Gruinard, Mr. Cain, is a closely-guarded military installation, and what they’re up to there is an equally closely-guarded secret.”

I said politely: “But not, no doubt, from Interpol.”

“Aye, from us too.”

“And from you personally?”

Another long pause. He said at last: “I don’t know if I’ve the right...” He sighed. I waited, and he said: “It’s a Bacteriological Warfare Research Center, Mr. Cain.”

I said patiently: “As a matter of fact, I knew that already. What I want to know is...what exactly are they manufacturing there?”

That pause again. He said at last: “Could I speak with the Colonel again, if you don’t mind?”

I handed Fenrek the phone and said: “Tell him, Fenrek. This is what we’ve all got to know. And now.”

Fenrek said into the phone: “If you know, Superintendent—even if you’re not supposed to—tell him.”

He gave me back the instrument, and I heard the rich ripe voice say slowly: “They’re manufacturing a thing called botulinum toxin, Mr. Cain, though I’ll not be able to tell you much about it because I’m happy to say that I don’t know very much. All I know is...”

I interrupted him. I said quietly: “Don’t bother, Superintendent, I know a lot about it. Do you know a man named Loveless?”

“Aye. Michael Loveless is our Minister of Education.”

“Wrong Loveless. This one’s Arthur, born in the Farne Islands, in St. Agnes, but now lives in Africa.”

“St. Agnes, Mr. Cain?” I could hear the wheels turning.

I said: “Aye, but don’t let it bother you too much. Except that there’s a likelihood he knew your Alexander Stewart. What’s the population of St. Agnes?

“About eighty souls, give or take a couple.”

“Then he did know him. They must have been kids together. And that’s all I wanted to know. Thank you, Superintendent. You want to say hello to Fenrek again?”

“Aye, but tell me...what’s the matter with him?”

I said: “Nothing, now. He’ll be on his feet again in five minutes.”

I passed the phone over to Fenrek and listened to them exchanging small talk for a moment. I tasted his barley soup; it was excellent. And when he’d rung off, I said: “You’d better pass the word around. What you’re fighting is botulinum toxin. Under ideal conditions, that’s a toxin of which one ounce is the fatal dose for sixty million people.”

He stared at me.

I said: “More precisely, one sixty-millionth of an ounce is a fatal dose for one person. Somehow, some of it has found its way to Portugal, and the question of finding Loveless is now a good deal more worrisome, isn’t it?”