I said: “It’s a word you’re very fond of. What’s the definition?”

“Of non-people? Hell...” He thought for a while and said at last, with a wary sort of grin: “I suppose you could say anyone excepting present company.”

He jerked his head at Van Reck. “He’s non-people because he can’t talk even if he had anything intelligent to say, which he doesn’t. Histermann’s non-people too, really, though he doesn’t realize it. But the real non-people are the blacks. There’s not one of them knows his arse from his elbow, or knows what he’s fighting for. If I’m on their side, they just do as I tell them. If they’re on the other side, they just listen to someone who tells them to go out and get the mercenaries, and then they walk into my ambushes and get killed off, and there’s another little victory, chalk it up on the board. And when there are no non-people left in Nigeria, or Ghana, or Mali, or anywhere else, it’ll all be starting up again just over the border. Any border.”

“And you work for the highest bidder, is that how it goes?”

He was enjoying the opportunity to talk. I thought: what does a man like that do in the bush, with no one to vent his spleen on? I knew the answer; he goes mad, it’s a common enough occurrence in the bush not to excite comment:

He said, very thoughtfully: “No-o, that isn’t strictly true except in theory. But sometimes...Take Tshombe, for example. Back in those days, Lumumba was offering us a lot more than the Katangese could ever have paid us, but I didn’t trust him, and I always half-thought that Tshombe was right, and he was, dammit. But the U.N. drove most of us out of there; we had to cross over into Uganda. There, it’s a tossup, all of them at each other’s throat and none of them in the right, so we went with the Banyankole tribes. They were at the throats of the Batoro, non-people like all of them; only the Banyankole had the diamond mines, and so...” he shrugged, “that threw us into their camp. We did pretty well, too.”

Now was the time. I said: “Is it just money you want? For God’s sake....”

He looked at me shrewdly, and waited. I waited too. He said at last: “What’s on your mind? Cain, did you say?”

Well, there it was at last, and the idea was his, not mine; he was sure of that.

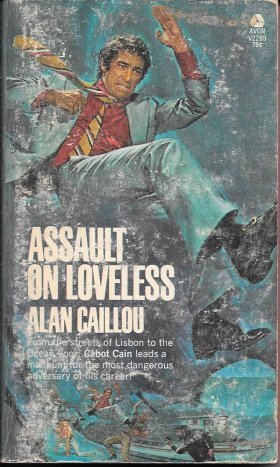

I said: “Cabot Cain, and what’s on my mind is a deal. I’m surprised that it didn’t occur to you.” The friendliest fellow in the world, I said earnestly: “I could get you a round million dollars, American, for every ounce of that culture you’ve got. That’s a pretty damn good price for a commodity that costs fifty cents an ounce to produce.”

He was smiling gently. “Four million dollars.” Question answered; I was watching his face as carefully as I’ve ever watched anything in my life. He said dreamily: “I’m almost tempted. With a guaranteed passage to South America, that sort of thing?”

“Something like that”

“And who’d put up the money?”

I could see what he was thinking. He’d been too long with no one to talk to, no one except his non-people. He was disappointed that the deal I had in mind wasn’t the one he’d hoped for; or wondering if he’d hoped for too much; or perhaps calculating the risk of that better deal and wondering if it was worth it.

I said, making it sound as though this wasn’t what I was after either: “I’ll get the money somehow. A lot of people would pay handsomely to avert the danger of plague in Africa.”

“The do-gooders?”

“If that’s what you want to call them.”

“A bit dicey, isn’t it? I mean, there I am sitting around a police station while Cabot Cain—that’s a hell of a name! American, aren’t you? Where from?”

I said: “San Francisco. You were sitting around the police station.”

“Och, I was too, and Cabot Cain is passing round the hat asking for benevolent contributions to get this mass murderer on a ship to South America with four million dollars in his pocket.”

I didn’t like that repetition of the four. I thought about it for a while and decided it was merely fortuitous, not thrown at me deliberately. Loveless had many virtues, if that’s what you want to call them; but a chess-player’s mind wasn’t one of them.

He said again: “It’s a bit dicey, isn’t it?”

“I could manage it.” I hoped I sounded unconvincing enough, and was sure that I did.

He shrugged. “It’s an academic question, anyway. I don’t need money that badly.”

“What do you need, Loveless?”

He sighed, and thought for a while, staring moodily at his feet. He didn’t look a bit like the villain of the piece now. He was a sad man with a terrible dream that perhaps he knew could never be realized. A vicious, unholy dream; but none the less I couldn’t bring myself to hate his guts as I should have done. I found myself hoping that his killing would not be at my hands.

He said, and he sounded troubled: “I don’t know, really, and that’s the truth. I only know that when I’m at work, I’m a kind of...a kind of king. There’s nobody does my job better than I do; Cain. Nobody. There’s a thousand mercenaries, five thousand perhaps, fighting all over Africa. Most of them are bums, but not all of them. Some of them fight for money, some for the left against the right or the right against the left, because that’s what they believe in. Some of them fight for one tribe against another just because they just screwed some pretty little virgin in tribe ‘A’. Some of them fight for whoever’s losing, just on principle, and some of them fight for whoever’s winning for the same reason. And some of them fight just for the hell of it, because that’s the only thing they’ve ever learned to do. I guess that’s my reason, really. But to tell the truth, I’m not too sure of it.”

I said, very quietly: “You are not fighting against non-people, Loveless. You are fighting against God.”

He snorted: “Him too, I know, He killed my...” He broke off and took a deep, unhappy breath.

I said: “Your mother.”

He looked at me with a strange expression in his eyes: not angry, not surprised, not hurt. He said: “You know about that? You’ve really done your homework, haven’t you?”

I said: “I know the progression.”

“Progression?” He sounded irritable. “I wish you’d talk more clear.”

“Progression’s the only word. A red tide that killed your mother with mussel poisoning. A disastrous epidemic in Scotland that looked like the same without the red tide, and finally, your own red tide to make it look real when we had more mussel poisoning here. Yes, I’ve done my homework.”

Now, he took the plunge. He said: “Ever been in the bush, Cain? Or are you a city man?”

“I’ve been in the bush.”

“You don’t carry a gun, that means you don’t know how to use one.”

“It means nothing of the sort, I am a crack shot.”

He said carefully: “If I invited you to come in with me...? Maybe I need someone who knows about this stuff. What would you say?”

I had to be careful not to leap at the suggestion, not even to let him think it wasn’t entirely his idea.