“Voran, you break my heart. If the Pilgrim had not so much as commanded me to send you after the Living Water, I would never have allowed it. Do you not see? If even one of the pilgrims is found dead, you will be cursed with your father’s guilt for all time.”

Voran mused on his first memory of Antomír. Voran was eight years old at the time and had been sick for weeks. Breathing through his nose had been impossible, and so he had not really slept for days. He was blowing his nose with all the vigor of his warrior blood when Otchigen and the Dar walked into the house after a week’s hunt. The Dar, his laughing, dark eyes a better cure than all the horrid-smelling mustard wraps that Mother tried on him, turned to Otchigen.

“He has a nose like a horn,” Antomír had said. “Next time, bring him to the hunt. He could prove useful with such a horn.” At which point they both laughed until the tears flowed. Voran had loved him intensely from that moment.

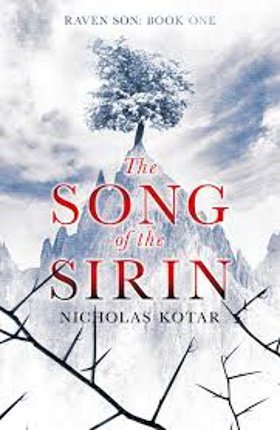

“Highness, you must think me touched by madness,” Voran whispered. He led the Dar to the high place and returned to pick up the fallen crown. He placed it on the Dar’s head—it was colder than ice—and stood to his right on both knees. “You must believe me. I have seen the Sirin. I have spoken to her. I have soul-bonded with her.”

A knot of muscle stood out on Dar Antomír’s jaw. “Tell me everything, Voran.”

And Voran did, beginning with the echoes of the song. He spoke of the white stag, at which the Dar tutted, smiling. He tried to describe the Lows of Aer, which left the Dar pensive. He spoke of the Pilgrim, the Covenant Tree, the Living Water, and the soul-bond with Lyna.

“Lyna?” asked the Dar, his eyes wide with surprise. “She is of the eldest Sirin. Older far than the Covenant, older far than the Three Cities.”

Voran’s heart leaped in his chest. “You do believe me, Highness.”

Dar Antomír sighed with a rueful smile. “Yes, my son. I have seen the Sirin myself, in the deepwoods, many years ago. Sometimes I think I still hear a song, but I can no longer catch the melody.” He seemed a hundred years older at that moment. “Nonetheless, no one else will understand. I can grant you no more clemency, Voran. The Dumar is on edge as it is. They want you imprisoned. Some want you publicly flogged. It must be exile for you.”

Voran’s heart plunged to his ankles.

“Voran, tomorrow Vasyllia’s armies go to seek out the enemy in the open field. You cannot go with them; indeed, I think you might find a knife in your back if you did. But I will give you a chance at restitution. You will follow the trail of the pilgrims you lost. If Adonais wills it, you will find them before any enemy—human or not. Mirnían insists on going with you, though I threatened to have him imprisoned for self-will. I will also give you the young warrior who spoke at the council. The red-bearded one, Dubían. He has uncommon strength, though he is gentle as a maiden in peacetime.”

“Highness, I do not deserve your…”

“That is right, you do not,” said the Dar, with a flash of youthful anger. Then he smiled again. “I do not do this for you. For whatever reason, both the Pilgrim and the Sirin have indicated that you must find the Living Water. If you do, and if you see the pilgrims safe to one of the outlying strongholds, I will recall you to Vasyllia. If we live that long.

“Now,” he said, standing up and wincing in pain. “You have a much less pleasant task before you. Sabíana has the strength of a she-wolf, but you wounded her deeply, Voran. Put it right.”

Sabíana's eyes were a rare dark brown that warned of deep unhappiness. Voran steeled himself against a conversation he would have given years of his life to avoid. She refused to speak first or even to look at him for longer than a second.

“Sabíana, I—”

“Voran, what has possessed you? You have become strange to me. Half-mad with phantasms and omens.”

Her every word was a hot knife-thrust.

“This Covenant you seem so intent on,” she continued, now jeering. “How do you imagine it happened? Adonais’s hand descended from the clouds and signed a parchment with letters of fire?”

“Sabíana, a broken Covenant explains the death of the tree, the omen of the skies, the burning of Nebesta, the invasion…”

“Voran, these are but the aberrations of history. They happen. It’s our misfortune that they all conspire to happen now, but there’s no need to seek for mystical causes. It is unbecoming of you.”

“You saw how the Dumar welcomed the refugees, Sabíana. The Covenant commands us to care for the Outer Lands’ people as we would for our own. A camp of refugees denied entry into the richest city in the world? What more confirmation do you need?”

“The Covenant is a fairy tale! Yes, in the stories it makes sense, but you cannot apply it literally. Even if we have failed in some sacred duty, what sort of a god punishes his own people only for forgetfulness? Is that our gentle, loving Adonais?”

On some level, Voran agreed with her. But he had already considered the implications of that line of reasoning. If faith in a gentle god had led the Vasylli to neglect the good of others, then perhaps they imagined Adonais to be different than he really was. Perhaps Adonais was a jealous god.

“Has your father told you?”

“Of his plan for you? Yes.” She turned away from him and folded herself into her black shawl.

“I suppose you wish me to release you from our promise?”

She turned back to him, her eyes blazing. “I would sooner run you through with your own sword!” She seemed shocked at her own vehemence, but only for a moment. “Why can you not give me your heart, my bright Voran? I have tried so hard to dispel the restlessness that keeps driving you away from me, but you have built a wall around your heart. I can comfort you; I can be your joy. But you must let me.”

“Sabíana, you’re upset, I understand.”

“You understand very little, for all your new-found importance. Why do you keep shutting yourself from me?”

Voran found no words. She was right. He felt deflated, more tired than he had in years.

“What would you have me do?” He asked.

She slowly released the muscles tensing her body like a bowstring. The beauty seemed to seep back into her relaxing curves, the warrior princess transforming into a sinuous black swan. She took his hand and kissed it, caressing it gently.

“It is not for me to tell you what to do,” she said.

His stomach lurched, and warm desire groped him. His head began to swim. His heart raced like a deer through the trees. He enfolded her into his embrace—how small and brittle she seemed! For a moment, everything was foolishness—the Raven, the Living Water, the coming war. It was all even mildly amusing. What else mattered except her embrace?

A kind of madness was on him, a savage excitement. The brittle thing in his arms was now not Sabíana, but a thing. He could do anything he wished with her. He kissed her violently. She shuddered for a moment, then melted into it. His hands itched to caress her.

Cutting through the noise of blood rushing in his ears, Voran heard the song of the Sirin, faint, plaintive. In his mind, he saw Lyna as she had met him, wings outstretched in the birches. She shone in a delicate light that sharply framed her feathered outline, but now she wept. The desire faded, and Voran felt a rush of tenderness for Sabíana. He pulled away from her, laughing gently. Sabíana’s face was flushed, rosy. She smelled faintly of tuberose. She rested her head on his chest.

“I adore you, my Voran. I’ve never had so little control over my own heart. Even in your absence, you fill me. I see you even with my eyes shut. All the memories, brilliant as the sun shining through the rain.”

For the first time in his life, he felt calm in her presence.