Thomas Broderick

What’s the most interesting thing that’s ever happened at Ray’s? Good question.

You even brought an old tape recorder. Man, I haven’t seen one of these in forty years. Is this the stop bu...

Sorry. I won’t touch it again. Well, if I’m going to answer your question, you need to know a little bit about this place, and about the kind of people who drink here.

My name’s Mark. I started coming to Ray’s about forty-five years ago. This place was called The Secret then, a reference to how the bar started as a basement speakeasy. So that makes Ray’s, what, a hundred and thirty-five-ish years old.

Anyway, back in my day it wasn’t an old men’s bar. You’ll see it, too, when you’re old enough. Bars are born as young men’s bars. They turn into middle-aged men’s bars before finally becoming old men’s bars. A new generation picks up the torch, or the bar dies. Circle of life.

On my first visit I met Ray, the owner. He was in his early fifties then, and had been a bartender the entirety of his adult life. Andy, his son, was twenty-three, my age. He’d just graduated from college and decided to work for his dad. Being a bartender is in his blood, and he’s done well by it.

It was about the time I started coming that Ray was getting fed up with how people would drink in silence, their attention glued to smartphones or tablets. Ray would go entire nights and say no more than ten words to his customers. How can a bartender tend his bar if all he gets to do is pour drinks?

Ray did what he thought was right. Read that sign up there: If it was made after 1989, keep it outside. The man carved it by hand from a slab of reclaimed oak. Why 1989? That’s the year Andy was born.

At first Ray caught a lot of hell for it. Some asshole actually brought one of the first cell phones, a massive brick of a thing, just to piss off Ray. Screamed into it all night. Funny thing was, something I didn’t know at the time, that those phones didn’t work even then. Guy was talking to himself!

Ray just shrugged it off, and most people actually enjoyed the change. Ray even bought some old arcade cabinets and pinball machines. Yep, those are them back there, the same ones. Andy even keeps a jar of old quarters for customers who want to try the games. You wouldn’t believe how few people carry real money these days. I bet no one under fifteen has ever even seen a quarter.

When Ray died, Andy changed the bar’s name to honor his dad. He kept Ray’s rule. No cell phones became no Glass, no Glass became no ContactVue, and so on and so on. Don’t get me wrong, I’ve used all that stuff. Gotta respect the wishes of the dead, though. Every time I come in, I check my gear at the door with Andy’s daughter, Rita.

But most people like it, I think. Ray’s gives them something new to try, even if new is simply taking an hour or two away from modern life.

Well, I think I’ve given Ray’s a good introduction, one that Ray’d approve of. Back to your question. Hmm, I don’t think that’s a hard one at all. It happened six months ago, when Nous showed up.

It all started on a slow Tuesday. I’d noticed thinner crowds over the previous few months. The novelty of the place had worn off over the years, I guess.

Andy was trying to keep up his good humor that night, but I could tell that something was weighing on him. “What’s up, buddy?” I asked him as I finished off my first beer.

Andy set down the glass he was polishing. “Business is lousy,” he said, avoiding my gaze. “Been that way for over a year. I’ve burned through my savings.”

“Any ideas?”

“Well,” he said, pouring me a fresh lager. “Possible investor came by last week. Young guy. Still had acne. He likes the place, how it’s not really nostalgic, just simple.” He smirked. “I took it as a compliment. There’s a catch, though.”

I waited for him to speak.

“I’d have to break Dad’s rule.”

“Now, hold on, Mark,” Andy said before I could start in on him. “He said it would be real... how did he put it... unobtrusive. Some sort of game, apparently. He can make it look like one of our old arcade cabinets. Besides, there’s space between Tempest and Eight Ball Deluxe.” He looked up at the sign over the bar, as if his father was glaring down from it.

Andy was clearly justifying a bad decision, but who was I to argue? I didn’t want Ray’s to shut down. That would break Andy’s heart, and if this kid could deliver something that wouldn’t bother old timers like me... whatever.

In fact, I didn’t even notice Nous when they delivered it the following Sunday. I had a lot on my mind that night. My best friend, Henry, was going through a rough time. For the record, Henry’s not his real name. The guy deserves some privacy, especially after what Nous put him through.

Henry and I first met in the early twenties when our company decided to combine offices. We did developmental testing for semi-autonomous drones. Not the big military ones, little ones used for home delivery.

Ray’s was our hangout after work. It was a good place to wind down. Eventually we both met girls and married, had our own kids. Our wives were friends, our children played with each other. For a couple decades we all had a good time.

About a year ago Henry’s wife, let’s call her Ann, was diagnosed—breast cancer. It was too far along to do anything for her.

After the funeral Henry became a shut-in. Before coming to Ray’s that night I had been at his house for half an hour, begging him to visit the bar with me, said that it would help him relax. Henry didn’t budge.

So, no, Nous didn’t stand out at all the day it arrived. Andy had to point it out to me. It was ugly. The cabinet was mat black, no gloss, no art like you see with old arcade cabinets. The only design was its name printed above the screen in block white lettering. On both sides of the single joystick were three cherry red buttons. I figured it was designed for both right and left-handed players.

“So that’s it?” I asked.

“Yep,” Andy said, sighing. “All I had to do was sign for it. They plugged it in. That’s it.”

“Is it even on?” I asked because the screen was blank.

“Yeah. Starts up when you put a quarter in it.”

“How is it?”

Andy handed me a quarter from his jar. “Give it a try. I think you’ll like it.”

I took the last swig of my beer and, feeling just a little tipsy, walked over to the machine. The mechanism made the familiar clink when I fed it Andy’s quarter.

“Grab the stick,” Andy said before I had the chance to ask why nothing was happening.

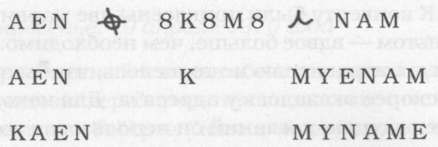

Calibrating appeared on the curved screen the moment I touched the joystick. Do not let go of controller or experience will end.

Experience, I thought to myself. What pretentious crap. I remember when games were...