Clive Tern is a writer of short fiction and poetry living in Cornwall. He was once a stockbroker, but exchanged the fantasy of the real world, for the reality of fantastic worlds.

Sometimes he writes about writing being difficult at clivetern.com.

Beachcomber

Mark Toner

SF Caledonia

Monica Burns

As promised in Issue 3, this book will be another delightful surprise from a well-known Scottish author—someone who is never first associated with science fiction. The author of Gay Hunter, published in 1934, was James Leslie Mitchell (1901-1935). If you don’t recognise this name, you’re more likely to be familiar with his nom-de-plume, Lewis Grassic Gibbon. It may seem odd that the author of the well-loved classic, A Scots Quair (which includes the Scottish school system’s favourite, Sunset Song) wrote science fiction, but Mitchell was actually an avid reader of the genre. The list of his best-loved authors and influences include Jules Verne and H.G. Wells. Gay Hunter is one of a few science fiction novels he wrote.

Lewis Grassic Gibbon and his celebrated trilogy, A Scots Quair, enjoy their place in the spotlight, but the unique SF canon, published under his birth name, James Leslie Mitchell, go virtually ignored and unstudied by academics. It’s time we gave Gay Hunter some attention. Having studied Sunset Song to death at school, I was delighted to read a science fiction novel by the same author. It blends a lot of the enjoyable elements of Sunset Song—the strong female protagonist, the coming of age, the experience of first love, the intensely beautiful descriptions of the natural world and its impact on the human spirit—but set in a post-apocalyptic London. There are even some lasers.

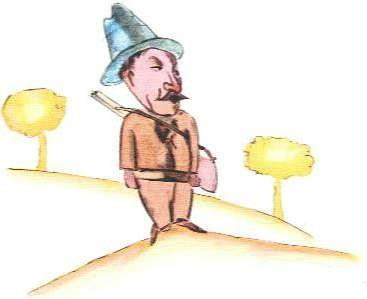

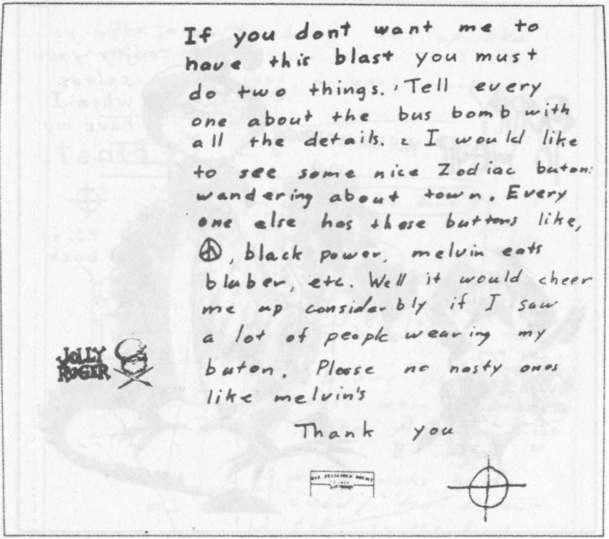

So what is it about? Don’t be confused by the title. Gay Hunter is the name of the protagonist: a young American archaeologist, visiting London for an academic conference. At the start of the story, by the roadside, she encounters a very unpleasant Fascist man, Major Ledyard Houghton, and offers him a lift in her car. That evening, Gay despairs to find that they are checked into the same hotel, and they end up being seated together at dinner. After quarrelling over their respective ideologies, and the Earth’s future fate, Gay challenges him to try an experiment taught to her by her father, to peer into the future. This experiment is based on a real life theory of time and the power of the sleeping mind to enable time-travel, by J.W. Dunne in his book An Experiment with Time, published in 1927. Gay and Houghton make a pact to try the experiment that night.

Gay did not expect it to work. She is horrified to find that she has not only glimpsed at the future in her dreams, but has travelled bodily through time. She wakes up, naked and alone in a world given back to nature so completely that it seems like the ancient, primitive past. Gay is alarmed to find herself in an era far into the future, long beyond the aftermath of a nuclear war that tore the world to pieces.

She is not alone in her travels. Shortly after she awakes, she encounters Major Houghton, who had apparently also kept to his promise that he would try the neo-Dunne experiment. But unbeknownst to Gay, Houghton had been on the telephone that night with a Lady Jane Easterling, the spoiled patroness of his Fascist group, and told her about their experiment. She too tries it, and so wakes up in the same time as Gay and Houghton, in the same predicament—naked and completely and utterly lost. It is not long before the unsteady alliance of convenience between Gay and the two Fascists begins to break down, and fundamental ideological tensions begin to seethe. Especially when they encounter the Folk. Human society did survive, but at first sight seems to have regressed to a more primitive state. Nomadic hunter-gatherers travel together with tame wolves in a society very different to the twentieth century. Among them, there are some who speak English, learned from what is known as the Place of the Voices amidst the ruined buildings of their ancient past. This ancient past is still in the future for Gay’s timeline, so she hasn’t a clue what has happened to the world in the interim.

Befriending the Folk, especially a young singer called Rem, she tries to find traces of her lost world, the old London, and what happened to society to destroy it so completely. She also seeks a way home to the twentieth century. As Gay gets to know the hunters and their ways of life, she learns more and more about their society, and about herself. A recurring theme in a lot of Mitchell’s work is the discovery of the ‘essential self’, the wild and deep part of everyone that civilisation stops us from expressing. In his novels, Gay Hunter, The Lost Trumpet and Sunset Song alike, the discovery of this part of the self is unfailingly beautiful, always twinned with sumptuous descriptions of the natural world, and makes for a lot of ruminating long after you’ve finished the book.

Gay, Major Houghton and Lady Jane go their separate ways. Being so detached from nature, their essential selves, and possessing such extreme Fascist views, Lady Jane and Houghton look on the Folk with a very different attitude to Gay, and their influence on the peaceful native society could have disastrous consequences on this golden age.

Gay Hunter is exciting, thrilling, often funny, and has the effortless, insightful beauty of Sunset Song. True to what you’d expect from Lewis Grassic Gibbon, it is absorbingly written, vividly depicted, full of striking commentary on civilisation and the self, and populated with engaging characters you really care for.

James Leslie Mitchell

James Leslie Mitchell was born in Hillhead of Segget, a croft in Auchterless, north Aberdeenshire, to a farming family. The Mitchells moved south of Aberdeen when he was eight years old to a region called the Mearns, where he spent the rest of his childhood. Both his birth name and his pen name are hosts of his heritage: the names Mitchell, Leslie, Gibbon and Grassic are all family names from both his mother and father’s sides and can be traced back in the north-east for around three hundred years. His background was strongly agricultural, but when it came time for Mitchell to enter the world of work, he had a very ambivalent relationship with farming life, and decided to work in Aberdeen as a journalist. In 1917, however, he returned to his family in the Mearns and took up farming once again. Desperate for an alternative career, he joined up for the army in 1919, like many young men his age, and later enlisted in the RAF and was sent to fight in Egypt. He hated the army, but as they say, nothing is wasted on a writer, and his travels provided him with plenty of fuel for his craft, particularly in books such as The Lost Trumpet, another of his SF novels and set in Egypt.

James Leslie Mitchell was born in Hillhead of Segget, a croft in Auchterless, north Aberdeenshire, to a farming family. The Mitchells moved south of Aberdeen when he was eight years old to a region called the Mearns, where he spent the rest of his childhood. Both his birth name and his pen name are hosts of his heritage: the names Mitchell, Leslie, Gibbon and Grassic are all family names from both his mother and father’s sides and can be traced back in the north-east for around three hundred years. His background was strongly agricultural, but when it came time for Mitchell to enter the world of work, he had a very ambivalent relationship with farming life, and decided to work in Aberdeen as a journalist. In 1917, however, he returned to his family in the Mearns and took up farming once again. Desperate for an alternative career, he joined up for the army in 1919, like many young men his age, and later enlisted in the RAF and was sent to fight in Egypt. He hated the army, but as they say, nothing is wasted on a writer, and his travels provided him with plenty of fuel for his craft, particularly in books such as The Lost Trumpet, another of his SF novels and set in Egypt.

Mitchell was finally was able to devote his life to his writing at the age of twenty-seven, but he was dead by thirty-four. He died from a perforated stomach ulcer. Although the literary world was grieved to lose him so soon, those final seven years of Mitchell’s life were extremely productive. In that time he wrote 17 books; fiction, non-fiction, biography, academic texts and short stories.

Dying so young, he didn’t live to see WWII, but the themes in Gay Hunter are spookily far-seeing with its Fascist characters, nuclear warfare, society divided into Hierarchies, the degradation and exploitation of the ‘Sub-Men’ by a ruling class. Ideas like these have echoes of Hitler’s visions, although the war had not yet happened. The signs were all there in current affairs for Mitchell to read: fascism and communism were on the rise, and the stage was being set for the war and its atrocities to begin. In Gay Hunter, there is a brief mention of Hitler and Mussolini—chilling for the modern reader, knowing what Mitchell did not.

Mitchell’s influences were not only political and scientific. There were exciting social and literary events happening around him that doubtless made an impact on his work. At the time in Scotland the Scottish Literary Renaissance was in full swing, headlined by the likes of Hugh MacDairmid and Edwin Morgan (and Sunset Song is considered one of the movement’s defining works), and 1928, only six years before Gay Hunter’s publication, the suffragists had succeeded in getting women the right to vote in the UK. Like A Scots Quair’s famous heroine, Chris Guthrie, Mitchell’s female protagonist, Gay, is such a well-rendered character that it is almost hard to believe she was written by an early twentieth-century man.

Gay Hunter is generally agreed to be James Leslie Mitchell’s best and most developed science fiction story, and unfortunately it was his last. He intended it as a ‘companion book’ to his 1932 novel, Three Go Back, using a lot of similar ideas of time travel and exploring primitivism to comment on contemporary society.

In a letter to his friend Christopher Morley, introducing Gay Hunter to him, Mitchell writes that “this book has no serious intent whatsoever. It is neither prophecy nor propaganda. It is written for the glory of sun and wind and rain, dreams by smoking camp-fires, and the glimpsed immortality of men”. But, as Edwin Morgan claims in his introduction to an edition of Gay Hunter, this book “affords a good example of trusting the tale rather than the teller”, for Mitchell has more to offer in this story than just a fun, science fiction romance.

There’s a Lewis Grassic Gibbon Centre in Arbuthnott, Aberdeenshire, near Laurencekirk, if you want to know more about him.

Gay Hunter

James Leslie Mitchell (Lewis Grassic Gibbon)

Art: Monica Burns

She looked round the room and its sham antique oak, all solemn lines of fiddley curlicues. A great sloped mirror showed herself. Being still very young, she looked at that self with attention, but not too much. The room was deserted but for the waiter bringing the soup. Then she saw Houghton enter.

He had changed from hiking-dress—perhaps he had carried that lounge suit in the rucksack. It certainly looked a trifle crumpled. And as certainly it improved his appearance. Gay drank soup and looked at him with a faint interest—he had good shoulders and a straight back, and the cool hauteur and rangy straightness of the English Army officer of myth and rumour. As good almost as meeting an ancient Mayan in the flesh.

Funny how much better the lounge suit was than the hiking-shirt and shorts. But she’d thought that often of the feeble attempts at rationalisation in clothes that men and women made. The scantier the garments, the more feeble and ridiculous and lewd the wearers looked. The Victorians were perfectly right and logical, bless their padded bottoms. Either you clothed yourself or you went naked. To sling shorts or the various pieces of a bathing suit over this and that portion of your anatomy was to make those portions suspect and taboo....

Houghton was standing beside her. He was stiff. “I understand the waiter would like us to share a table and save him work. Lazy old devil. Do you mind?”

Gay shook her head, eating tepid fish. “I don’t think so. “She turned away her eyes from another fasces badge, in the lapel of the lounge suit collar this time. “How’s the headache?”

He sat down, half in profile. It was a stern, good, absurd profile. “Gone for the time being; but no doubt it’ll come back. ...No, damn you, I told you I didn’t want soup. A chop, man.”

This was to the waiter. He shook a little, old and servile. Gay gently restrained herself from flinging the remains of the tepid fish at the correct, absurd profile. She had often to restrain herself over bodily assault in matters like that. The damned horror of any animal addressing another like that! Then she saw the twist of Houghton’s face. Poor idiot.