The amount of inventions and concepts are staggering. I simply will not be able to list them all, but here are my favourite few: mankind has worked out how to control the weather and adjusts it to suit; energy is harvested from volcanoes; there are armies of tamed animals trained to undertake tasks of burden; birds are trained to sing in choirs; and humans each have a pair of metal wings that enable them to fly, and it has become common that people enjoy courting in the sky. A few of Blair’s other flights of fancy happen to be uncannily far-seeing and bear remarkable resemblance to the inventions of the digital age: there are microscopic books, enabling the ease of transport of thousands of volumes of literature; there’s a system of pneumatic tubes which enable audio broadcasts and objects such as newspapers to be sent immediately to anywhere in the planet, meaning the whole world gets the same news at the same time (completely normal to us in the internet age, but a marvel to Blair in 1874); and there are powerful telescopes that allow someone to see across the world to anywhere they choose, which sounds more or less exactly like satellite imagery.

Blair predicts infinitely optimistic things for mankind, declaring poetically that “Science has confiscated the contents of Pandora’s box”. He bravely attempts an explanation about how the world’s evils have been eradicated by science, but occasionally it is brushed aside so carelessly it becomes rather self-parodying - especially when the narrator casually adds that murder is a thing of the past. Although the President Diogenes Milton presents a very positive picture of the world’s progress, it reminded me of, in our own world, the way history often relayed to us—the ways in which often a country’s national narrative, the stories it tells itself about its own history—are often distorted in order to maintain systems of power and oppression. With a report as positive as this from the President of the World Republic, I couldn’t help but wonder what he is smothering beneath the mask of a shining utopia—about who is being repressed and the lies the World Republic is telling itself about its society and the state of the planet in order to convince itself and the people that they are doing the right thing.

It is not a huge leap of the imagination to make these suggestions: there are some elements of the book that hinted to me that not all is as good in the world as Milton suggests. For example, it is decided in the World’s Parliament that the mountains of the world are to be levelled to the ground for aesthetic purposes, because they are “scabs on the face of fair nature”. Blair often writes poetically, and sometimes poignantly and he does so at this moment, “Thus, amid universal acclimation, it was decreed that the everlasting hills should be everlasting no longer.”

Not only are the mountains to be destroyed, but vast swathes of the world seem to have merged into one. There is a moment where Edinburgh is described as “a beautiful district in the city of Britain”. To me this picture sounds like a nightmare! A world where Man has so entirely consumed the natural world that there is no countryside left, no mountains left to climb or gaze at, it sounds too scarily like the future we may run headlong into if we’re not careful. On top of all that, globalisation has gone to the extremes that there is one centralised government, one religion that everyone follows, zero diversity or nationality. That sounds more like the basis of a dystopia, or a daydream for the small-minded.

In what world could murder no longer exist? Is the justice system so strict that fear keeps the people in check? Or have they cracked their own version of Precrime as in Minority Report? Such details don’t stand a great deal of digging—unless of course, you are a writer and like to ask yourself what if as a spring-board for inspiration, in which case this book is a gold mine.

I realised, while reading this book, that I was a little harsh in judging it. For a modern-day author to include important world-building details with such shaky foundations like this, critics would go right through them—but for a someone writing in the 1870s, someone whose whole life seems to have been contained within a seventy mile radius, it is really rather impressive. When compared to other SF authors we’ve met in this series, such as James Leslie Mitchell and George MacDonald, writers whose travels to foreign lands must have broadened their horizons and therefore their imaginations, Andrew Blair is not known to have travelled much further afield than his home region of Fife and neighbouring Angus. Considering not only the time period in which he lived, but his exposure to the world on the short time he lived on this planet, he had an incredible imagination. Also, it must be acknowledged that he was only 25 years old when Annals of the Twenty-Ninth Century was published. It is not to say that Blair never travelled outwith his home counties, just that his life is not well-documented. Most of the information I managed to scrape together came from the aforementioned article in the Dundee Evening Telegraph, announcing the death of a well-known and well-liked young doctor in Tayport.

Blair was born in Dunfermline in 1849, studied Medicine at the University of Edinburgh and from there he went on to become a doctor. He practiced in Coupar-Angus, Ceres and Strathkinnes and finally in Tayport, where he died after eight or nine years of service to the community there. Tragically, he was only 35 years old when he died, leaving behind a wife and one daughter. The Dundee Evening Telegraph reports that he caught a severe cold that meant he was confined to his house for months, which ultimately badly affected his lungs and ended his life in the January of 1885.

The article praised his character, his conduct as a doctor and his writing: “In Tayport he was highly esteemed. He was a public-spirited man, and took much interest in all the affairs of the village. [...] He was a most genial and entertaining companion - his conversation being full of jokes, anecdotes, and apt quotations - and as a friend he was generous to a fault.” They went on to say he was “a singularly well-informed man of refined literary tastes. He was widely read on many subjects, and being possessed of a powerful memory, he could use his information with telling effect both in conversation and in writing. He was indeed a writer of unusual ability.”

Now since moving to Dundee myself, and seeing the modern Tay Bridge every day, with the remains of its predecessor standing as stumps beside it (the original bridge famously collapsed in 1879 during a storm), I can’t help but wonder about Andrew Blair. Living in Tayport during this decade, a town under ten miles away and within sight of the bridge, he would have living memories of both its construction and its tragic fall. He was practising in Tayport while its foundations were being laid. I wonder how much this inspired his book—the optimism and excitement surrounding the construction of a new feat of engineering, a record-breaking structure, the longest bridge in the world at the time.

Annals of the Twenty-Ninth Century was published just four or five years before the Tay Bridge Disaster—I would love to know what Blair thought, whether or not it shook his soaring optimism for progress. It seems the anxiety about great disaster accompanying great achievement wasn’t absent from his mind, as one of the chapters in Annals is titled ‘The Great Accident of the Age’ and describes how a rogue boulder, during a dismantling of a mountain tumbled down the side of the mountain and crushed a town.

The extract I have chosen reminded me so much of the 1902 silent film by Georges Méliès Le Voyage Dans la Lun (A Trip to the Moon). Yet Blair was voyaging to the moon almost thirty years before this groundbreaking fantasy film.

Just before this extract, Diogenes Milton and his friends (who are, like many of the book’s characters, brazenly named for eminent individuals) Shakespeare Socrates and Stephenson Watt have returned from their first botched attempt at reaching the moon. I like this passage for its sense of realism. Blair has put a great deal of thought into imagining what it would be like to travel into space. He is realistic in the limits of the technology and the characters learn from their mistakes and improve the technology for the next venture. Then he describes the enormity of the task, the sublimity of outer-space and the anxieties of space-travellers. Blair has a powerful imagination that doesn’t only imagine the spectacle and the fantasy, but ruminates on the physical and psychological implications of in space travel.

It is easy as modern readers to grow bored of scenes that look down on earth from space, but remember Andrew Blair was writing in a time where that view was still 87 years away, and even with his wild imagination he didn’t expect it to be possible until the 29th century.

Annals of the Century Twenty-Ninth

CHAPTER XVII

Between Heaven and Earth

Andrew Blair

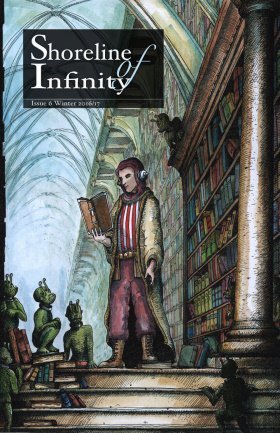

Art: Monica Burns

The idea of a journey to the moon was now rescued from the dungeons of scepticism. The hitherto untrodden cantons of ultra-aerial dynamics were soon overrun by the feet of research. Improved altimeters, non-aerial barometers, and thousands of trans-atmospheric apparatus were invented weekly. The mountain tops of success are ever invested by pathless glaciers and precipices. Determined to storm these redoubts, we advanced with hearts garrisoned with the ammunition of courage and perseverance. Accordingly, we prepared to make another expedition into the firmament. We commenced by facturing a more complete ultra-mundane locomotive, which comprised such an amazing concentration of ingenuity and such an aggregation of inventions, such an embodiment of skill, and such an incorporation of volatility and strength, that it took two years to focus these wondrous properties into its workmanship. It was a mechanical marvel. The same size as the last, it was a hundred times more powerful, and it possessed the additional advantage of requiring a crew of only half the number.

The trial trips in this engine extended over six months, during which time we greatly increased its velocity, and introduced into it a large budget of little comforts. The grand but abortive attempt was then made to invade the moon. Our trans-aerial ship was not only stocked with the most nutritive food, but a new idea was adopted, in supplying each of its mariners with physiological antitriptic apparatus. Such was their excellence, that a few grammes of food and a table-spoonful of water daily were rendered quite sufficient for the maintenance of life. The other arrangements were so consummately ingenious, that we verily believed we would be enabled to cross the mundo-lunar gulf. Our effort was sublime in its boldness. Perhaps our band might never again see earth. Sacrifices on the altar of scientific research, we might be wafted like meteoric stones upon some other world. Our bones might not return to the dust whence they came, but be revolved for an infinity of time in an infinity of space. The thought could not but make us turn our eyes to our Father in heaven, bold in the assurance that though our remains might be waifs in the universe for thousands of ages, we would still be supported by His gracious hand. Even if martyrs, we were dying for the greatest cause of this great age. When, in the past, men went to the field of slaughter to murder or be murdered, merely on account of the silly squabbles of kings as to what kind of flag should flutter over a certain piece of ground, could we grudge to risk our lives for the noblest of projects in this the era of cosmopolitanism, the epoch of the millennium?

Our crew, consisting of Copernicus Galileo, Stephenson Watt, Caxton Arkwright, Shakespeare Socrates, and myself, left our terrestrial home amid the benedictions of our fellow-men. Millions had come from every quarter of the world to view the great ascension, and the scene and services merited their assemblage. The very circumstance that it was Mount Ararat from which our Hegira to the moon took place, lent a sacredness to the solemnities. Where the ark had first rested we were now about to embark in another ark, in which we were to seek another Ararat in another world. Henry Bunyan, who conducted the services, spoke with an inspiration which have endowed his words into the classics. Millions on the Mount and in the air, by means of their auroscopes, heard his molten language; and never did ears listen to a more impressive discourse, or eyes witness such an impressive sight. At length our balloon weighed anchor. A procession of ten hundred thousand aerial mariners escorted us to the suburbs of the atmosphere, anthems being played the while with such beauty, as swathed our souls in a halo of heavenly joy. Arrived at the shores of the air, we left the great sight and the triumphant sounds behind us, and launched into the dark gloomy trans-aerial ocean. For a while our eyes and hearts wandered back to our friends, but our duty soon urged us to direct our eyes upwards, and centre our resolutions in winning the moon. Our speed was equally pleasing to ourselves and our brethren on the earth. With natural delight we saw terrestial objects exact a small and still smaller dividend of our retinae. Every incident omened well. The non-aerial breathing machine, the acoustical devices, and the log-lines, worked with success, while our spirits were buoyed up with the most cheerful expectations. At mid-day we had our first meal, according to the antitriptic system. Two and a half kilogrammes of food sufficed us all, yet each of us had enough to satisfy his requirements. Not since the multitudes had fed on the loaves and fishes did ever any company have their appetites slaked with so small a proportion of viands. Chameleon-like, we might have almost have been said to have lived on air. But the mere skeleton of a summary must suffice for the log-book of the trans-terrestrial voyage. In the first week we journeyed 1,100 kilometres daily on an average, during which time we observed four undiscovered moonules. In the second week, in consequence of being nearer the moon, and having a greater share of its gravitation and less of that of the world, we averaged 1,300 kilometres daily. In the third week we increased this to 1,600, in the fifth to 2,000, in the sixth to 2,600, and in the seventh to the amazing velocity of 3,500 kilometres daily. Up to this point we surmounted every difficulty, though all the while deeply alive to the peril of our position and the wildness of our adventure. Now we had collisions with meteors, anon we were drifted out of our course by a constellation of moonules. Nestled in mid-air, 80,000 miles from a world, we lived in regions in which there was no air to breathe, no food to eat, and no water to drink. Though the physiological plans which enabled us to breathe where there was no atmosphere, and to fast without suffering starvation, were akin to perfection, our eyes longed to view the fair face of our mother earth —our mouths watered to taste its fruits, and even our souls thirsted to feel the enjoyments of home. Coffined within a small car, we felt as if we lived without feeling life. Beyond the scenes and influences of humanity, our very senses were famished. The appetites of sight, smell, touch, taste, and hearing, each suffered a dearth. While our mind’s machinery was in full play, our physical feelings seemed exiled from their true spheres. A small balloon was our world, wherein our ears only heard the sound of our own voices, and our eyes viewed the awful sight of a double firmament with its zenith and nadir. Heaven to us was not a canopy, but a great rotund vault, of which we were the centre—a vault marvellously bespangled with star brilliants, and a vault whose milky way was a silverway, and zodiacal light an aurora. Half the day we looked down upon the sun. Day and night a firmament with myriads of stars lay beneath our feet. Alone in the trackless tracts of immensity we saw our native world dwindled into a moon. We were in regions concurrently cheered by sun-light, moon-light, world-light, and star-light. What appearances could have been more reverence-inspiring than those we viewed? Could the wildest of Dantes, Miltons, or Coleridges, have supposed anything more wonder-fraught than a miniature world of a few metres in diameter, with a population of only five inhabitants, and in possession of a firmament containing two moons to which in size ours was a dwarf and in lambency a rush-light—a firmament not of 190°, but 380°, in which a sun, two moons, the milky way, the zodiacal light, and a complete muster of the stellar hosts, shone simultaneously, undimmed by the medium of any atmosphere ? Yet truth, which so out-fictions fiction, rendered these wonders realities. Above our small entity of worlddom was the earth-like moon, below was the moon-like earth, and all around the glorious unclouded stellorama of infinity. What conditions could arouse more intense feelings or excite more sublime ideas ? Even the writings we composed in those vacuous realms breathe a religious fervour, nobility of sentiment, and earnest glowing eloquence, equalled in none of our earthly works. Could any circumstances so estrange us from the sordidness of the world as the possibility that we might never return to it in the body ? Never was such a sermon vouchsafed us on the littleness of man, and his utter dependence upon Providence. Those who have never left the fire-side of the earth cannot appreciate the numberless bounties which rain unconsciously upon them during every throb of their pulse; but we who were removed from its scenes were enabled to see them by the powerful telescope of their absence.

But I am brought to the straits to which we were driven after having lived eight weeks upon the unnatural method essential for territories without food, air, land, or water. Our strength began to fail and our courage to be damped, so that we were outflanked, and forced back to the conviction that science was still unable to cope with the multitudes of exigencies which such a journey as ours entailed. Nevertheless, we held out for another week, feeding our fortitude on our moonward ambition. Our speed during this time was four times that at our outset. On this account we stood exactly half-way between the earth and its consort on the sixtieth day of our extraterrestrial exile. Each day had seen these two visually great, but astronomically small, orbs changing, the moon growing larger and larger, the earth smaller and smaller, both merging from their gradations, of new to full moon and full to new moon, new to full earth and full to new earth. Having proceeded so far, we again tried to blow up the embers of our determination. Our hearts being magnetic towards moonland, we strove on three days longer, when, to our unutterable grief, Galileo took seriously ill. The rest of us being far from well, we were forced amid heart-rending regrets to behold the death of our cherished hopes, and to take a longing look at the moon, after having journeyed towards it more than half-way. We then relaxed our dietetic system, halted our aerial chariot, and made a few final investigations before sounding our retreat. Applying our scales, we found the force of gravitation so small that our balloon only weighed a few pounds and ourselves a few ounces. We next threw a few small articles out of our bark, and found they only fell a few inches in a minute. Interested in a tenet which science had so long held, but which the senses had never before witnessed, I boldly jumped out of the balloon into the great abyss of Vacuity. Unnatural though it seemed, I fell not, but then I was standing on nothing. Like Peter, my faith led me to walk on an unwonted element, but, like him, my valiantness soon melted. Though at first delighted with the singular sensation of being suspended in a vacuum, I became terrified when I looked down, and still more when, in my absence of mind, trying to advance towards my aerial vessel, I saw all my exertions brought me not nearer it one iota. I had forgotten, indeed, in leaping out, that the element in which I had ventured was not one in which I could swim. My friends laughed heartily at my needless anxiety, and to comfort me Stephenson Watt leaped out and bore me company, while he, at the same time, handed me a rope with which we were enabled to re-enter our craft. After a few further experiments and investigations, night came on, and night though it was, we at once shaped our course to the earth. We erringly thought we should not err by trusting only to our instruments. The action of the engines, joined to the increased force of gravitation, made us dart down with a velocity at which speed itself might have been startled. Every moment our momentum increased, but as there was no atmosphere to clog our inertia or to make us feel that when falling we were falling, we had only the sensation of being stationary, while the world was a huge ball advancing upward, and the moon another in full retreat. Such was our composure, that we failed to take the precautions which were so necessary—we failed to note how quickly the world was becoming world-like and the moon moon-like. Shakespeare Socrates and Stephenson Watt were busily engaged in completing some investigations; Caxton Arkwright was studying the action of our bark’s machinery; while I was employed in nursing our sick brother Copernicus Galileo. Our speed, moreover, was so much beyond our calculation, that we were startled when daylight dawned four hours afterwards, and showed us the earth at a distance of only a few hundred miles. It was now too late to reverse our engines, and apply the ultra-aerial drag to impede our impetuous impetus. With the energy of despair, however, we strove to lessen our danger, but, short of a miracle, nothing could enable us to escape, and a miracle not being forthcoming, we crashed against the atmosphere with such suddenness and violence, as kindly bathed us in the sweet waters of insensibility. Happily, those on earth had noticed our Icarus-like fall, and had prepared a suitable arrangement to save us from serious injury. Despite this, the concussion was so great, that each of us, Vulcan-like, had our legs broken. Such was the suddenness of the accident, and such the wild overthrow of our senses, that our ship was wrecked ere we had time to realise we were near the world. Our ultra-aerial equipments were undoffed, for, in our stupor, we knew not the moment when we had entered the atmosphere. As for our wounds, it was only the case of Galileo that gave us any concern, on account of his previous indisposition. Happily he, as well as the remainder of us, rallied so quickly that our misfortunes did not vex us so much as the damage to our balloon and our instruments. A few days’ hygiene repaired our tabernacles, but it took weeks to refit our mutilated locomotive. The accident, as being the only one which had happened in the world since the Matterhorn catastrophe, was deeply deplored; but it could not daunt the irrepressible energies of man to make renewed sorties to the moon. Our mission, notwithstanding its failure, had reaped a rich harvest of scientific discoveries, and glowed with the omens of future success. The composition of the trans-aerial ether, its electrical peculiarities, the countless shoals of meteoric with which it abounded, its peculiarities at different altitudes and under diverse conditions, had not only been investigated, but their phenomena completely unveiled. We had likewise proved the possibility of man living for weeks and even months by artificial physiological adaptations in the regions of vacuity.

Become a Friend of Shoreline

If you want to join the Friends of Shoreline, please support the magazine by subscribing via our website

www.shorelineofinfinity.com

Our ambition is to pay our writers and artists the full rate for their efforts, and this can be achieved with the support of our readers.

Remember, subscribe to Shoreline of Infinity or our friend on the cover won’t be able to make his next visit to the magazine.

Interview: Stephen Palmer

Interview: Stephen Palmer

From his debut 20 years ago with Memory Seed, Stephen Palmer has become one of the most individual voices in British science fiction and fantasy.

Here he talks to Gary Dalkin about his recent work, including his new Young Adult Factory Girl trilogy.

Gary Dalkin: Your new trilogy, which I haven’t had an opportunity to read yet, is YA. Before that, your most recent books, Beautiful Intelligence and its sequel No Grave For A Fox are near-future hard science fiction set in same universe as Muezzinland. They are particularly appealing in that they strive to present as much as possible a global vision, spanning different cultures and continents, and all levels of society, from homeless street musicians in Fez to the five star world of the super rich. Is this kind of hard SF something you plan to write more of? Will there be further additions to the Beautiful Intelligence series?

Stephen Palmer: I think it’s unlikely that I will return to the Beautiful Intelligence world; events in genre fiction would have to spin out of control for that to happen. I’m the sort of author who follows his muse, which usually means artistic satisfaction and relatively little commercial success. Not that I’m in this for the money, you understand! As for the inclusion of what might be termed the ‘lower levels’ of society into my work, I’ve always been drawn to ‘outsider’ characters and issues, being myself very much a fish out of water in British, conservative, technophilic, capitalist society. Alas, ‘ordinary’ people in modern Britain really are outsiders, since the ruling elite serves only itself, including through the ballot box. Though I can come across sometimes as a rabid Lefty, I’m really much more of a Green Liberal—the ultimate political outsiders in Britain.

Then there’s the whole Africa thing. That started out as a love of the music, but it’s broadened to a fascination with the land and its cultures, especially North and West Africa. I bought a kora last year (the West African twenty-one string harp) which I’m hoping to learn to play. A beautiful musical instrument. My sympathies lie very much with ‘ordinary’ people who have ‘ordinary’ lives being shafted by the semi-insane men who rule them. I’m anti-Tory, anti-religion, anti-royal, anti-patriarchy; in other words, pro-human. I was recently described by one reviewer as having a tendency to didacticism, but I think that comes more from having a social conscience than anything else.