Distantly, I can feel fingertips following the angles of my face, stroking my hair, the line of my lips. “I’m sorry. I’m sorry I never told you, Yoltzin. But until I did what needed to be done, we could not speak the plan aloud. I know you believed. But She... The count of days is wrong. We are not the sixth age. We are but the death throes of the fifth. We are part of the catastrophe of the age’s end. We are not living in a new and glorious age, we are merely the last of a dying one, needlessly dragging out the pain of our people. I am just ending what needs to be ended. I am just saving you.”

Every word of his is heresy. I try to force open my eyes, but I do not have the strength. I breathe in shallow, swift gasps. I manage a low whimper of pain, but not words. The journey has been more taxing than either of us anticipated.

“The others will build a new world without the need for endless sacrifice. There will be no part in it for a priest old before his time, a priest with this much blood on his hands. There will be no part in it for an old sacrifice either, an old sacrifice who still believes. But I had to. I had to save you. I just...

“I killed the Goddess. I won’t be able to tell you when you wake, but I need to say this now. I killed Her. I slipped a knife into Her heart when I stapled shut Her chest. She will bleed.”

At the mention of blood, my mind turns to the red flowers and the blossoming bruises on the Goddess. In more ancient times, they called such human sacrifice a flowery death. It was said to be the most noble way to die. I remember the pictures we were shown as children, the men and women sprawled out in bright blossoms of blood, each splatter uncurling like a petal from their heart.

“She will bleed under Her skin,” whispers Itztli. “The blood will clog the parts that are inside Her. She will lose too much. She will die before they notice.”

“She...” The immensity of the realisation pushes me to form words. I croak them out despite the pain. “She wanted you to...”

Itztli recoils.

“She wanted you to. I saw Her. She showed me.” I keep my eyes closed, but I fumble a hand towards Itztli. I stroke a finger down his jaw. His skin is cold, too cold. Instead of the suncoils and the skyrail, my mind returns to the smile I saw in my dream of light. It dawns on me, colours unravelling endlessly in my mind like all the sunrises I have only ever imagined, pressing grubby fingers on yellowing picbook pages. “She hears everything. She hears everyone. Even those who fight against her priests and her enforcers. She can only bear our sorrows and suffering for so long. She wanted you to end it. She wanted a new age.”

“No.” His voice is thick and warm against my ear. “This is not yours to forgive.”

“There is nothing to forgive.”

He does not believe me, but he holds me tighter, probably too tight. It barely matters through the drugs and the pain.

I try to focus on the way he and I fit together: my head on his shoulder, the tangle of his hands, the twinning hold of his legs. I want to think only on the way his cold skin and the knot of his scars feel against me. I want desperately for this to be the only thing that matters. He has torn out most of his augments and he smells of old blood and sweat. I wonder if he sought to flay off his skin this way, in a penance of sorts. He does not carry his crime lightly.

Pain cuts through these thoughts and the erratic beat of the mechanical heart consumes me; I hear it echo in my ears.

I cannot forget.

•

Look above, child.

The sun you see today is not the sun that shone above the first people. Five ages and five tyrant suns have risen and fallen. Ours will one day fall as well.

The first was the Lord of Near and Nigh. But his brother, the Feathered Serpent, was envious of how the once crippled god shone, so he knocked him from of the firmament with a stone club. Without the sun, the people were lost to darkness and in that darkness they turned on one another. They consumed each other and in their barbarism, they became jaguars.

The next age was ruled by the Feathered Serpent. He died in wind and rage, with its people clinging to trees and becoming monkeys.

He Who Is Made of Earth ascended as the next sun but his wife was kidnapped and thus he wallowed in narcissistic grief. Besieged by prayers, he destroyed the world in a rain of fire. To escape, the people became birds, soaring above the flaming sea.

The fourth age ended with its people becoming fish as the goddess had a heart too soft, too kind and too broken. She flooded the world with her black tears. A man and woman survived, hiding in a hollow tree, but found themselves being turned into dogs by the gods. We do not live in a time of just gods.

The fifth sun, Left-Handed Hummingbird, demanded unending sacrifice of hearts upon his altars of blood and bone. But the moon, She whose Face is Painted with Bells, knew this to be unjust, so she made war upon him night after night. But war was a stalemate and unable to witness the suffering of the people, she poisoned her own brother.

Then came the time of blood and burning. We have lived in the shadow of the fifth age, in its final breaths. As with the end of every age, the trials made us into beasts as we cling to survival. The Goddess with the Human Heart could not bear the suffering any longer and the Last Priest killed her in an act of mercy, ending the time of sacrifice.

And so dawned a sixth age. There is a new sun and a new people, but tyrants do not live forever. I hear the Last Priest and the Girl with the Divine Heart wander the wastes. I hear they are near.

The wheel of the heavens will turn again.

Jeannette Ng was born in Hong Kong and now lives in Durham. She designs and plays live roleplaying games, makes costumes and writes speculative fiction. Her debut novel Under The Pendulum Sun is published in October 2017 by Angry Robot.

These Are the Ways

Premee Mohamed

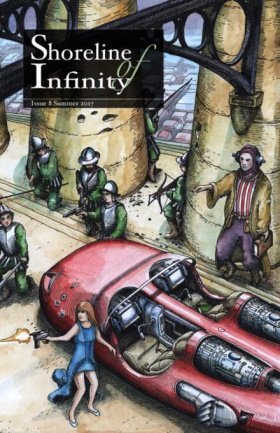

Art: Mark Toner

These are the ways I wished for you to die:

Fighting, to assure your family of honour.

With courage, for the comfort of your immortal soul.

Swiftly, that you might not suffer at the end.

And at my side.

The plasma arc hit low, scorching calf and flank, and at first we thought it was not fatal, not even serious; we’d all seen burns like that in training, same shape, same size. You joked as we pulled off your melted boot and snipped away the damaged remains of your uniform trousers. “Hey guys, do I need to shave this week?”

“Smooth as a baby’s butt,” Kara said, setting aside the scissors and cracking open her damaged first-aid box. Medics and their black humour. As a sniper, I was useless except as extra hands for the hurried field dressing. I held your ankle on my shoulder, encircling the knobbly warmth with my entire hand, your eyes meeting mine accusingly between frantic blinks that barely cleared the pain-sweat. I should not even have been there, your eyes told me. That was the rule. Useful personnel: continue the assault. The wounded (“We do not say ‘hurt’,” the major had snapped): repaired and sent back into action if possible; gathered and guarded if not, to prevent the Akhjians from taking POWs. As a last resort, gassed.

Kara worked quickly – anaesthetic aerosol, antibiotic gel, a lint-free paper sleeve, pressure dressing, a blast of UV to harden the resin enough to bear weight. Someone had sent one of the privates, big Gilmour, to fetch you a new boot. Wounded himself, he gamely zigzagged across the battlefield between pops of green and violet light, looking for a size 7.

“This is bad,” murmured the other medic, stiffly rising and shutting his kit. “Maybe we should—”