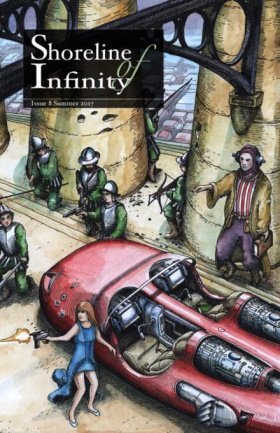

Targets

Eric Brown

Art: Jessica Good

I was watching the three-dee with Kelly when the programme was interrupted.

“Uh-oh,” she said.

I gripped her hand. “Don’t worry.”

She turned and stared at me, the hologram pulsing on her forehead.

I stared at the three-dee in the corner. The frame was empty; then a tall man in a black suit appeared.

Kelly began to weep.

The suit said, “Citizens, your son, Edward, has been selected by LAPD for immediate targeting. Please make an appointment at your closest LAPD clinic within the next five days. I will now return you to Sunny Days in Idaho...”

Kelly jumped up and crossed to the bedroom door. I joined her, staring in at our sleeping son. He was curled up, warm and dreaming. Innocent.

“Was I a fool, Joe, for thinking…?”

I scratched my forehead where the hologram was. “We both hoped, Kelly. We dreamed.”

I wondered at the chances of the child of two targets being selected. A statistical anomaly, I told myself.

We killed the three-dee and went to bed.

I couldn’t sleep. At two, with Kelly sound asleep beside me, I rolled out of bed, dressed quietly and left the apartment.

It was a risk. Venturing out after dark was always a gamble for people like me and Kelly – and for Edward, now. But I needed a drink; more, I needed to talk.

I kept to the shadows, skulking like a rat. I knew where the night cops usually patrolled, but you could never be sure. Sometimes they liked to ring the changes, to keep people like me on their toes.

The bar wasn’t signed. It was underground, literally. I crept down the steps, entered the code on the door and slipped inside.

It was like coming home.

A dozen people like Kelly and me, holograms glowing in the semi-darkness, sat quietly drinking.

I ordered a beer and drank. Thirty minutes later, I ordered another. I felt a little better then. At three, Al came in, fresh off his night shift.

“Hey, my friend.” He clapped me on the shoulder. “Whatcha doin’ here?”

I told him about Ed’s selection.

He pulled a face. “Hey, that’s tough. I’m sorry. How’s Kelly?”

I shrugged. “Cut up. What do you expect?”

“That’s life, Joe. We gotta learn ta live with it.”

“Yeah,” I said, and bought a couple of drinks. “Shit.”

A few beers later, I staggered home. I kept to the shadows, but I wasn’t afraid now. Dutch courage. Let the cops shoot me. Only tomorrow, when I’d sobered up, would I regret my foolishness, regret potentially making Kelly a widow at twenty-three.

So we took Ed to the LAPD clinic, and a blank-faced nurse zapped our son with the laser and a neat, round hologram target implanted itself in the centre of his forehead.

Our life changed, after that. No more risks. With Ed’s welfare to think of, we imposed a curfew on ourselves. Never go out after sunset, only during the day; keep to busy areas. Avoid patrol cars, and don’t ever go anywhere near police stations.

We got by.

Ed was bullied at school, of course. I remember the time I’d been singled out for the hologram on my forehead, and I felt powerless to help him. Words were useless. He had to learn to look after himself, just as Kelly and I, and all the others had done.

He grew into a great kid.

One day – he was around seven, eight – he came in after school and said, “Dad, I want to be a teacher when I grow up.”

I could have wept. “That’s great, Ed.”

I glanced into the kitchen to see if Kelly had heard. She was facing the sink, her back tensed.

He’ll forget the ambition in time, I told myself, move on to something else.

That night, in bed, Kelly said, “You gonna tell him he can’t be a teacher?”