"And your new Orpheum?"

"The Fine Arts Committee will carry on the work. The chairman

is Lady Skellane Laverty; I have known her many years and she is devoted to the cause. She has brought me this book, long one of my favorites. Is it known to you?"

"You have not shown me its tide."

"The Lyrics of Mad Navarth. His songs hang in the mind forever."

"I am familiar with some of them."

"Hmm! I am surprised! You seem a--well, I will not call you a dull dog--let us say, a rather somber fellow."

"I don't think that of myself. The fact is that I am worried about my father."

"Let us talk about Navarth instead. Here is a particularly delicious segment. He glimpses a face for a single instant, but before he can look around it is gone. Navarth is haunted for days, and at last he pours his imaginings into a dozen wonderful quatrains, wild and fateful, surging with rhythm, and each tagged with the refrain:

""So shall she live and so shall she die And so shall the winds of the world blow by.""

"Very nice," said Glawen.

"Do you intend only to recite poetry to me?"

Floreste haughtily raised his eyebrows.

"You are privileged!"

"I want to know what has happened to my father. It seems that you know. I can't understand why you won't tell me."

"Do not try to understand me," said Floreste.

"I myself make no effort in those directions. I use the plural form advisedly."

"Tell me at least if, for a fact, you know what has happened. Which is it: yes or no?"

Floreste rubbed his chin.

"Knowledge is a complex commodity," he said at last.

"It must not be flung here and there tike a farmer scattering manure. Knowledge is power!

That is an aphorism worth committing to memory."

"You still have given me no answer. Do you intend to tell me anything whatever?"

Floreste spoke weightedly:'"I will say this, and you should listen closely. Clearly our universe is subtle and, one might say, palpitant. Nothing moves without jostling something else. Change is immanent to the structure of the cosmos; not even Cadwal of the Charter can evade change. Ah, beautiful Cadwal, with its fine lands and noble provinces!

The meadows are verdant in die sunlight; they invite the general habitancy wherein all creatures may take their special pleasures.

Animals may' browse and birds may fly, while men sing their songs and dance their dances, in peace and harmony. So it should be, with each consuming his share and each performing the work he finds needful. This is the vision of many noble folk, both here and elsewhere."

"So it may be. But what of my father?"

Floreste scowled and made an impatient gesture.

"Are you so dense? Must everything be shouted into your ear? Do you subscribe to those ideals I have just cited?"

"No."

"What of Bodwyn Wook?"

"Not Bodwyn Wook, either."

"What of your father?"

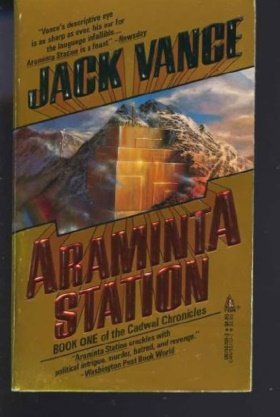

"Nor my father. In fact, almost no one at Araminta Station."

"Others elsewhere have more advanced views. But I have said enough and now you must go."

"Certainly," said Glawen.

"Just as you wish."

Glawen departed the jail and went off about his affairs, which kept him busy the rest of the day and the following morning as well. At noon, Bodwyn Wook found him taking his lunch in the Old Arbor.

"Where have you been hiding?" demanded Bodwyn Wook.

"We have searched everywhere for you!"