Occasionally, Marigold was caught doing things she shouldn’t. Once, while she eavesdropped on the royal steward explaining to King Godfrey that the kingdom of Hartswood had hired a wizard to levitate every pair of shoes in the village twenty feet in the air, she sneezed loudly three times in a row. She hoped no one had heard, but the steward himself — a man in a trim blue suit who was often unimpressed by Marigold — marched across the Green Gallery, pushed aside the loose wall panel, and looked down at her, more unimpressed than ever.

Marigold glowered back at the steward, mostly because she was too ashamed to look at her father. King Godfrey was probably scratching his beard just below the left ear, as he always did when he felt uncomfortable. “Marigold, my love,” said the king, “please come out of there.”

Marigold crawled out of her hiding space and brushed the cobwebs from her dress. “Hello, Papa,” she said. “I’m sorry.”

King Godfrey sighed. “I don’t suppose,” he said, “that you happened to end up inside the wall by accident?”

Marigold shook her head. She wished it had been an accident; then her father wouldn’t have sounded so disappointed. “I wanted to hear about the shoes,” she admitted. “Why did Hartswood make them all float in the air?”

“Because Hartswood,” said King Godfrey, pulling Marigold onto his lap, “is a place where no one has ever learned to act with decency. The queen herself hires wizards to curse those of us who’ve done nothing wrong!” He seemed much happier to be scolding Hartswood than he had been scolding Marigold. “And the other eight kingdoms are just as bad — always causing some kind of uproar, always bending the rules as far as they’ll stretch. That sort of behavior might be all right in the wildwood and the wastes, but it shouldn’t be allowed in any respectable kingdom. We certainly don’t allow it in Imbervale.” He turned Marigold’s face toward his own. “Especially not from a princess of Imbervale. Do you understand?”

Marigold thought she did. “I’ll be good,” she promised.

King Godfrey kissed her on the forehead. “Good,” he pronounced, as if she already were.

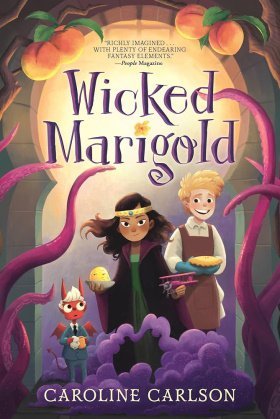

Marigold did try to be good. She learned algebra and history and seventeen polite ways to greet a stranger, and she played table tennis with Collin on his evenings off from the kitchens. She didn’t go anywhere she wasn’t allowed — except for the palace roof when no one was looking; or the Green Gallery when she felt sure she wouldn’t sneeze; or the carpentry shed, which turned out to be an extremely interesting place to sneak inside because it was full of wood and glue, wires and string, and all sorts of other things that could be turned and twisted and joined together in various ways. When the royal carpenter caught Marigold rummaging around under a workbench, Marigold expected her to scold or shout, but she just smiled a little, gave Marigold a box full of cast-off scraps, and shooed her back toward the palace. After that, Marigold spent long, happy hours in her bedroom fashioning contraptions out of the scraps — mostly kites at first, because they were simplest to make, but later a small bell that rang when you pulled an even smaller string, and a boat with sails that really moved up and down. She loved snapping the final pieces of a complicated device into place, holding her breath, and then watching as each gear and cord performed its own particular job to make the whole contraption work.

Some of her contraptions were useful, too. When Queen Amelia complained that the writing on many of the palace documents was too small to read, Marigold built her a magnifying frame out of old window glass and wire. And when Collin mentioned that it was hard to hear Cook’s instructions over the din in the kitchens, Marigold used some pulley wheels and a long rope to build a messaging system the kitchen staff could use to send notes across the room. She still couldn’t carry a tune well enough to soothe a dragon’s temper, and not even weeds grew beneath her feet no matter how many times she ran barefoot across the lawn, but at least she could be some help around the palace. She wasn’t perfectly good, but she hoped she was good enough.

When Marigold was eleven, she started working on a particularly tricky contraption, one she hadn’t yet dared to show her parents. “It’s a biplane,” she told Collin one evening, holding it out for him to see. It wasn’t much larger than Marigold’s hands, but she’d already spent weeks on it, fashioning its two broad wings and a bent-wire propeller that spun when Collin nudged it with a finger.

His eyes went as wide as Marigold had hoped they would. “Have you tried it yet?” he asked. “Does it really fly?”

Marigold grinned. “Let’s find out.”

Together they ran through the back passageways and up the long-forgotten staircases. “You be the lookout,” Marigold told Collin as she pushed open the window that led out to the roof of the east tower.

Collin groaned. “The lookout? Again?”

“I’m sorry,” said Marigold. She knew he wanted to climb out the window right along with her, but she refused to let him do anything that would get him in trouble with Cook, and he was sure to be noticed on the palace roof. He was six impossible inches taller than Marigold — despite being a full year younger — with a puff of light-colored hair that made him look, Marigold thought privately, like a towering dandelion. “I promise I’ll fly the plane where you can see it.”

“All right,” said Collin reluctantly.

With the biplane in one hand, Marigold crouched down on the roof tiles and edged toward the top of the tower. The evening light was golden, and the breeze seemed perfect for flying. Marigold hoped the contraption would sail at least to the edge of the palace grounds, even though she hadn’t entirely fixed the propeller, which had a tendency to stick. She stood up as straight as she dared, wobbled a little, reached back with one arm, and aimed the biplane toward the wildwood.

Down in the courtyard, there was a terrible shriek.

Marigold lost her balance. Her feet flew out from under her, the biplane flew out of her hand, and she slid a good ten feet downward. The plane plummeted toward the ground, and Marigold might have, too, if she hadn’t managed to stop herself by grabbing onto the edge of the roof and sticking her feet into the gutter below. She sat there for a moment, trembling.

“Marigold!” That was Collin, leaning out the palace window. “Are you hurt?”

Marigold looked down at her arms, which were badly scraped, and her legs, which were even worse. The leafy glop in the gutter was seeping into her shoes. She wiggled her toes experimentally; they squelched. “I’m all right,” she called back to Collin, “but I don’t think the plane is. Did you hear somebody shriek?”

As Collin nodded, there was another shriek from the courtyard below. This time, Marigold recognized the voice. “Mama!” she cried. She scrambled up the roof tiles, climbed through the tower window, and broke into a run, never mind the squelching.

Collin hurried close behind her. “Could you see anything from up there?” he asked as they sped down four flights of stairs. “Are you sure that was the queen?”

“I’m sure,” Marigold said. She couldn’t imagine what in all ten kingdoms might have caused her mother to break her usual decorum. An assassin’s arrow? A curse from a wizard who’d managed to slip through the palace’s protective spells? “Mama!” she called again as she and Collin raced out into the courtyard. “What’s happened?”

They weren’t the only ones who’d come running. It seemed as if half the palace staff was gathered there, murmuring to one another and craning their necks for a better view. Marigold ignored them all and pushed her way through the crowd.

There was her mother, and her father, too, with their arms wrapped around each other — and around a third person whom Marigold had never seen before in her life. Her parents were crying and laughing at once. So was the third person. That person was as tall as Marigold’s father and as dignified as Marigold’s mother, although the stranger’s gown was damp and extremely muddy. When she smiled at the king and queen, all the birds around the courtyard began to sing, and a nearby rosebush burst into bloom.

“Who is that?” Collin whispered.

Something in Marigold’s stomach began to twist. She knew exactly who it must be.

“Marigold!” Queen Amelia had finally looked up for long enough to notice her. “Come here, my darling, and meet your sister!”

Princess Rosalind had a lot of hair. It was even more golden than Marigold had heard, it flowed all the way down to her ankles, and when Rosalind wrapped Marigold in an embrace, it hung around them both in a heavy curtain. “My sister!” said Rosalind. “How wonderful! I’ve always dreamed of having a sister.”

Marigold took a step back, away from all the hair, where it was easier to breathe. She tried to remember one of the seventeen polite ways to greet a stranger but couldn’t come up with any of them. “Hello,” she said at last, because at least that was more polite than saying nothing at all.

“Rosalind escaped from Wizard Torville,” Queen Amelia said, beaming at them both. “Can you believe it? I’m afraid I shrieked loudly enough to rouse the whole palace when she came through the gate.”

“I thought you were hurt, Mama,” Marigold admitted. She remembered her own injuries then and hid her scraped-up arms behind her back.

But no one was paying attention to Marigold. King Godfrey put a hand on his elder daughter’s shoulder. “Are you willing, my dear,” he said, “to tell us how you made your escape?”

Rosalind nodded. “Of course,” she said. She sat down on the low courtyard wall, the crowd pressed closer, and Rosalind told them about Wizard Torville and the dank and dismal fortress where he lived at the far edge of the wildwood. She told them how, after fifteen years of making the wizard’s morning porridge and mending his tattered old robes, she’d opened her bedroom window one day to find a curious rope dangling all the way to the ground below. And she explained how, once the wizard had gone to sleep that night, she’d climbed down the rope and slipped into the trees, scrambling through the wildwood with the help of kindhearted squirrels who showed her the route back to Imbervale and fireflies who lit her way home.

Marigold had heard so many tales about Rosalind over the years that it was as if one of the characters from her storybooks had sprung off the page and come to life in front of her, sitting where Marigold often sat, with her arms around Marigold’s parents. And it seemed the tales had been true, even the most impossible ones: at this very moment, Marigold could see a pale-blue flower sprouting under Rosalind’s left heel. There were dozens of things she longed to ask Rosalind — what the wildwood had been like, and what sorts of spells she’d seen Torville cast, and who in all the kingdoms might have dared to tie a rope to the side of an evil wizard’s fortress, for a start — but whenever Marigold tried to speak up, the royal magician would ask a question instead, or the second undercook would push in front of her for a better view, or the steward would step on her toes. After a while, she gave up trying. She excused herself, although her parents were still so busy with Rosalind that she wasn’t sure they noticed, and went to look for her biplane.

It had crashed nose down beneath the east tower. Its wings were torn, its propeller was badly bent, and it looked more like the pile of scraps it had once been than a magnificent flying contraption. Marigold groaned and started collecting all the bits and pieces she could find, which wasn’t an easy task in the twilight. She could still hear laughter and cheers coming from the courtyard. Everyone sounded so happy — and why shouldn’t they be, when the kingdom’s long-lost princess had finally come home? Marigold was glad that Rosalind was back, too.