2.I am proud of my unique beauty as a Black woman, celebrating the richness of my melanin and the diverse features that make me who I am.

3.I am deserving of love, respect, and acceptance just as I am, understanding that my worth is not defined by society’s narrow standards of beauty.

4.My voice as a Black woman is valuable and important, and I have the right to express myself authentically and be heard.

5.I am resilient and strong, embodying the spirit of my ancestors, who fought against adversity and paved the way for me to thrive.

6.I embrace my heritage and cultural identity, recognizing the wisdom and traditions passed down through generations of Black women.

7.I honor my emotions and intuition, knowing that they are powerful guides that connect me to my inner wisdom and strength.

8.I am capable of achieving my goals and dreams, defying stereotypes and limitations that may seek to hold me back.

9.I celebrate the sisterhood of Black women, knowing that we are a source of support, inspiration, and empowerment for one another.

10.I love and accept myself unconditionally, embracing all aspects of my being as a Black woman and recognizing the beauty and power that reside within me.

188.Pearce, Diana. 1978. “The Feminization of Poverty: Women, Work, and Welfare.” Urban and Social Change Review 11 (1): 28–36.

189.Veeran, Vasintha. 2000. “Feminization of Poverty.” International Conference of the International Association of the Schools of Social Work 29 (July).

190.Finch, Charles. 1991. Echoes of the Old Darkland: Themes from the African Eden. Decatur: Khenti, Incorporated.

191.Diop, Cheikh A. 1987. Precolonial Black Africa: A Comparative Study of the Political and Social Systems of Europe and Black Africa, from Antiquity to the Formation of Modern States. Translated by Harold Salemson. Brooklyn: Lawrence Hill Books.

192.Saidi, Christine. 2010. Women’s Authority and Society in Early East-Central Africa. New York: University of Rochester Press.

193.Diop, 1987.

194.Okrah, Kwadwo A. 2017. “The dynamics of gender roles and cultural determinants of African women’s desire to participate in modern politics.” Scholar Works, 1–15.

195.Fyle, C. M. 1999. Introduction to the History of African Civilization. Lanham: University Press Of America.

196.Shandu, Mthiya. 2018. “A Stolen Legacy: The Matrilineality of Pre-Colonial African Society.” Medium. medium.com/@MthiyaneShandu/a-stolen-legacy-the-matrilineality-of-pre-colonial-african-society-5307b8db3e5a.

197.Razak, Arisika. “Sacred Women of Africa and the African Diaspora: A Womanist Vision of Black Women’s Bodies and the African Sacred Feminine.” International Journal of Transpersonal Studies 35 (2016): 14.

198.Walker, Alice. 1983. In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

199.Davis, Angela. 1983. Women, race, & class. Vancouver: Vintage Books.

200.Badejo, Diedre. 1996. Osun Seegesi: The Elegant Deity of Wealth, Power, and Femininity. Trenton: Africa World Press.

201.Goboldte, Catherine. 2002. “Laying on hands: Women in Imani faith temple.” In My Soul is a Witness: African-American Women’s Spirituality, edited by Gloria Wade-Gayles, 241–252. Boston: Beacon Press.

202.Amadiume, Ifi. 1987. Male daughters, female husbands: gender and sex in an African society. London: Zed Books.

203.Badejo, 1996.

204.Van Allen, J. 1972. “Sitting on a man: Colonialism and the lost political institutions of Igbo women.” Canadian Journal of African Studies 6 (2): 165–181.

protect

your

peace!

A Conclusion

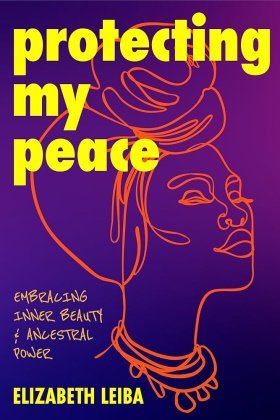

The journey of the African American woman, as explored in Protecting My Peace, is a profound tapestry of endurance, resilience, and a rootedness in rich cultural heritage. This book is a tribute to every Black woman navigating the intricate terrains of identity, past pains, and societal demands; it casts light on the path to inner tranquility, merging lessons from the past with contemporary insights and resources.

The obstacles Black women encounter span both historical burdens like chattel slavery and entrenched discrimination, as well as present-day societal pressures, such as media stereotyping and workplace inequities, that foster biases. However, this book emphasized the crucial process of recognizing, understanding, and healing from these challenges. By valuing Black history and culture, addressing both emotional wounds and systemic barriers, emphasizing holistic well-being, and advocating for a fairer society, a clear route to individual peace and collective advancement emerges.

Throughout the book, I accentuated the value of a supportive community. I underscored the importance of acknowledging accomplishments, crafting environments of trust and acceptance, and recognizing the transformative power of vulnerability and boundary-setting.

The pursuit of inner calm is a continual process. It necessitates introspection, tenacity, bravery, and, above all, self-affection. By merging age-old healing rituals with contemporary resources, confronting long-standing apprehensions, and challenging systemic hindrances, Black women can foster an environment conducive to comprehensive well-being. This is a restorative journey where individual healing not only betters oneself but also creates ripples, strengthening the broader community by setting positive examples and fostering mutual support.

Ultimately, to protect one’s peace is a profound act of self-acknowledgment. It signifies a dedication to personal value, development, and restoration. It’s about taking control of one’s story, navigating through life with tenacity, empathy, and affection, and actively engaging in self-reflection and community dialogue to reshape the narrative for the next generation. May this book stand as a lighthouse of optimism, an affirmation of the unwavering spirit of Black women, and a continual resource for all who aspire to discover and safeguard their tranquility.

about the author

Elizabeth Leiba is a writer, college professor, and advocate for Black businesswomen. She has over 100,000 followers on LinkedIn who range in age, race, background, and location primarily in the US, Canada, and the UK.