Months into her work at the Studio, Marilyn was still occasionally met with frosty reserve. This skepticism always sprang from her movie star glamour. Despite the black polo coat and newsboy cap, her beauty was undeniable. “Even with no makeup Marilyn looked terrific,” said Ben Gazzara. “I’ll never forget, Marilyn was sitting next to me, you know, during a class, and there was a scene being played called The Cat by Colette, and it’s about a young couple waking up after their wedding night and rolling in bed naked and Marilyn turns to me and says, ‘Ben, would you like to do that scene with me?’ And I said, ‘I don’t think so, Marilyn.’ I did refuse; I was a gentleman. You see, she scared me.”

Her overwhelming sensuality intimidated many of the younger actors, men and women alike. Carroll Baker admitted to having been jealous and insecure in her presence. Baker wrote of their first meeting: “I was already hating her for flaunting her availability at Jack [Baker’s husband] when she turned to say hello to me—and presented me with that same seductive quality of ‘Come on’! I suddenly felt drawn to her and leaned in a bit closer than necessary to accept her outstretched hand. Her hand was lusciously warm and plump, and I found myself clinging to it that added moment. Maybe I imagined it, but I thought I smelled the fruity aroma of sex.”

No wonder she never stopped worrying about being seen as the dumb blonde. She saw her classmates as colleagues—they saw her as a vampy pinup girl. Marilyn could have been the valedictorian of Vassar, and she’d still be ditzy until proven deep, bimbo until proven bookish. Had she fled the slick sexism of Hollywood only to be mired in a subtler sort of misogyny?

The sexism wasn’t always subtle. Carroll Baker recalls playwright Paddy Chayefsky stomping around the Studio with a smirk: “Oh, boy, would I like to fuck that!” When he was formally introduced to Marilyn at a Fire Island party he stared mutely at her chest: “Gee, I thought you’d be much fuller.”

Even benign rejection tended to crush the hypersensitive Marilyn. She once phoned Louis Gossett Jr. and asked him if he wanted to do a love scene with her from The Rose Tattoo. Gossett turned down the opportunity, so starstruck by his classmate that he knew he’d be unable to utter a single line.

“She would walk into class with a man’s shirt tied at her waist, her feet in flip-flops, the clean musky smell of Lifebuoy soap wafting after her,” he remembered. “Her hair, pulled back with a rubber band, was always a little wet, as if she’d just stepped out of a shower. She took a liking to me. I’d come in the room and she’d be going, ‘Where’s Lou?’ I couldn’t do any scenes with her, she was just one of the sexiest, most wonderful women I’ve ever met. I almost had to quit class because of her. With that Lifebuoy soap and that woman sitting there in the flip-flops—I swear, I’ve never been affected so much by a woman in all my life.”

Of course, Marilyn felt alienated after events like these. She had reached out—she who was new to the Studio, still a bit of an outsider. How was she to know that on her, flip-flops, rubber bands, and the scent of cheap soap were more potent than a cocktail of stilettos, red lipstick, and Chanel No 5?

But Marilyn was determined to stick it out. She’d spent years working with jaded directors who screamed “Cut!,” stubbed out their cigarettes, then ran home to their air-conditioned penthouses and B-list models. The Actors Studio was her chance to cast off all that cheap sequined drudgery.

As she threw herself into her work, Marilyn found herself remarkably suited to Method acting. It matched her nature, exploratory and inward-focused. Years earlier, photographer Philippe Halsman would get her into character by inventing situations: terrorized by a monster, or kissed by a lover, or drinking the most delicious mai tai. Lee dug even deeper, pushing her to excavate her own heavy past. She had plenty of dark matter to draw upon—foster mothers muttering doomsday prayers over breakfast, the orphanage with its cardboard birthday cakes full of dust. A born student, Marilyn took this very seriously, fearlessly conjuring bolts of memory, electric and terrifying.

She stuck to a grueling schedule—private classes with Lee on Wednesdays and Fridays, more classes Wednesdays and Thursdays, Malin Studios Tuesdays and Fridays, and psychoanalysis five days a week. She started arriving to class on time, relying less and less on Delos. The one time she was late (Dr. Hohenberg’s session ran overtime), she ran into her classmate Fred Stewart on 44th Street near Fifth Avenue. The doors were locked, and Marilyn was distressed. “Can’t we sneak in some way? I don’t want to miss anything.” Fred led her up an iron spiral staircase to a tiny little alcove above the stage. They huddled, hidden in shadows, Marilyn rapt and reverent.

Gradually, her dedication became obvious even to the most skeptical. Word quickly spread through New York’s theater circles that Marilyn was “working like a Trojan,” staying late at the Actors Studio, and skipping her rounds on the social circuit. “Must make much much more more more effort,” she wrote in her journal. “Remember you can sit on top of the world … Remember there is nothing you lack—nothing to be self-conscious about—you have everything but the discipline and technique which you are learning and seeking on your own—after all nothing was or is being given to you—you have had none of this work thrown your way—you sought it—it didn’t seek you.”

Around this time, Marilyn revealed to Shelley Winters that all of this—New York, the Studio, the psychoanalysis, and MMP—was a crusade. “That’s how she put it,” Shelley remembered, “a crusade to find the meaning of her own life that would give her the strength to succeed in being a ‘true actress.’ She said that—‘true actress.’ It was like she wanted to trade in who she had been and become something else.”

For the first time, Marilyn began to believe in her own talent. She had dared to provoke the studio system; now all eyes were on her. “She wanted what she deserved,” recalled her friend Ralph Roberts. “She was smart to refuse to do any more of their bidding. And if they fired her, she said they’d want her back but she’d only agree under her own terms.”

Marilyn was right: In ten months, Fox would be begging for her. She was about to bring Hollywood to its knees.

Eight

The Strasbergs

“Being a most serious actress is not something God has removed from my destiny.… It’s therefore my prerogative to make the dream of creative fulfillment come true for me. That is what I believe God is saying to me and is the answer to my prayers.”

MARILYN MONROE

Lee Strasberg became Marilyn’s guru and god—prowling the classroom in horn-rimmed glasses and rumpled-up garments that vaguely resembled hospital scrubs. “Speak up!” he’d bellow. “Try harder!” She’d watch, lips parted, smoke curling up from her cigarette, light streaming on her face like a da Vinci Madonna. Very quickly, it became obvious that she was Lee’s favorite.

This student-teacher bond extended far beyond class. Marilyn began dining at his home, often staying late into the evening. Lee and Paula took in actors as if they were stray kittens. Marilyn would soon become their favorite kitten.

A retired stage actress and Tallulah Bankhead’s best friend, Paula Strasberg was steeped in old theater lore—stage makeup, hot lights, and heavy red curtains. In her youth she’d played the sloe-eyed coquette. Paula loved anything trimmed, beribboned, feathered, or sequined, and in those days she looked like she’d stepped straight out of the Moulin Rouge. She’d given that up to be den mother of the theater tribe, and while black snoods and kerchiefs replaced modish little veils, there was still something lushly sensual about her. She was easy to picture as an overripe Colette, with her rich throaty laughs, lace handkerchiefs, and Japanese fans scattered round the floor along with smelling salts, tarot cards, and Bally dance slippers.

By the time she met Marilyn, Paula had become the official Jewish Mother of New York’s theater crowd. Her kitchen was legendary—the tiled floor in black and white checks, the fridge stocked with champagne, ice cream, and apple pies. Actors flocked to the kitchen every Sunday for brunch, piling their plates with bialys, lox, and cream cheese. Clifford Odets would be looming over the counter, drunkenly reciting poetry. Franchot Tone would barrel in bloodied up from a bar fight or howling over his latest girlfriend. At the Strasbergs’ you were permitted—even encouraged—to be different. You didn’t need to censor yourself, and “normal” was a four-letter word. EVERY EMOTION IS VALID said a sign Paula had pasted onto the kitchen wall. No wonder Marilyn felt so at home.

Paula was the perfect surrogate mother—always ready to coddle you with hugs or horoscopes or ice cream from Serendipity. Marilyn loved being mothered, especially by Paula, but she had much more in common with the prickly, cerebral Lee. She worshipped Lee’s passion, his focus, even his bristly intellectualism. True, he could be pedantic (he loved both Bach and Beethoven, but Bach was better—no matter what). This could grate on people—especially his family—but Marilyn loved rigid, uncompromising men. She could listen to Lee for hours, kneeling by his feet in the library as he smoked his pipe and rhapsodized on German philosophy or Kabuki theater.

The Strasbergs ensconced Marilyn as one of their own—even more than did the charming, affable Greenes, with their gorgeous family and white Christmases in Connecticut. For a changeling like Marilyn, even the warmest nuclear families could feel chilly and insular. The Strasbergs were expansive, sprawling, and delightfully imperfect. Their sense of family expanded to include anyone like-minded—the only prerequisite was talent. For Lee and Paula, art ran thicker than blood. They weren’t the kind of parents who’d blow you off for their daughter Susie’s ballet recital or their son Johnny’s rugby match.

This was fabulous for Marilyn, but Susie and Johnny found their father cold. Family closeness was entirely wrapped up in theater—the work. If Susie cried over a boy or a mishap at school, Lee would brush her off: “Darling, I’m really only concerned as this pertains to the work.” Johnny had it even worse: He wanted to drive a convertible, hammer houses for the summer, and eventually study medicine. He had little interest in theater, and at the Strasbergs’, theater was everything.

“Our door was open to many artists, but Marilyn was special,” remembered Susie, who at sixteen was preparing to appear on Broadway in The Diary of Anne Frank. It was obvious to Susie that Marilyn and Lee shared some strange affinity. Lee had always been surrounded by striking, talented women—Carroll Baker, Julie Newmar, Anne Bancroft—but Marilyn was different. What was it about this strange, floaty woman that had her flinty father so enthralled?

Susie remembers the first day she met Marilyn—both chilly and warm, it was just barely spring. The scent of pot roast and onions mixed with smoke from Lee’s pipe while Mozart’s concertos played softly in the background. Paula flailed her arms to signal “Quiet upon entry—Daddy’s coaching someone!” Lee never coached one on one—that was Paula’s job. Even more surprising was the sound of gentle laughter. Suddenly, Lee flung open the doors of his study and stepped into the dining room with Marilyn Monroe.

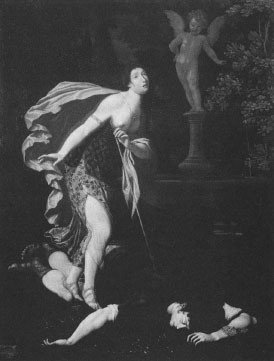

This was Susie’s vision of Marilyn—a sunbeam on her father’s arm, cottony hair, eyes huge and blue and skin as bare and vaporous as a Fragonard milkmaid’s. The hall was narrow and poky, and at dusk the light flickered against the red-flocked wallpaper, creating the chiaroscuro effect of smoky oil paintings. Marilyn stood out in powder pastels surrounded by a halo of light.

Susie watched, shocked. Her father—who never could stand being touched—cradled Marilyn’s arm in his own.

“Hi, I’m Marilyn Monroe,” she said. “You might not remember me, but we met in California.”

As if she possibly could have forgotten meeting Marilyn Monroe.

Visiting LA the year before, Susie had been crashing the Fox lot with her friend Steffi Skolsky, when she’d stumbled on Cukor’s Show Business set. She’d watched in awe as Marilyn danced and sang, “We’re having a heat wave, a tropical heat wave.…” And it was hot, crushingly hot, no breeze, palm fronds sticky and unmoving—or, as Paul Newman might put it, “just another lousy day in paradise.” Dozens of cameramen crowded the humid room. DiMaggio stood stone-faced, wiping his brow with a spotless starched handkerchief. In her limp brown hair and sickly dull skin, Susie felt self-conscious and puny. Then Marilyn slipped on the slick floor. She looked embarrassed and lost—almost desperate. And though Marilyn was a megawatt star, Susie felt sorry for her.

Later, she wandered upstairs in a trance, straight into Marilyn’s dressing room. “Come on, face, give me a break,” Marilyn sang to herself in the mirror, wiping off lipstick and flesh-toned pancake. She glanced up at Susie. “Sorry, I look like shit,” she said with a sigh, not at all angry at her little intruder. When she realized Susie was only a girl, she gasped, “Oops, sorry,” covering her mouth with a manicured hand.

In platform heels and a Carmen Miranda headdress, Marilyn towered over little Susie, who was barely five-one. In full makeup, she seemed larger than life. But now she was touchable, smaller, and far more beautiful.

“It didn’t seem possible,” Susie recalled. “Was this vibrant, shimmering mermaid who somehow managed to undulate on her high heel—this clear-eyed, normal-size girl—the same overblown, sexy, exotic creature I’d met a little over a year ago in Hollywood?” It’s as if this were the real Marilyn in her natural habitat, unleashed from Hollywood’s gaudy zoo.

After dinner, Lee lit his pipe and put on a Vivaldi record. Paula started the dishes, Johnny slinked off to his room, and Susie joined Marilyn in the huge study, which looked out onto Central Park. She watched Marilyn browse the bookshelves in awe—books on science, psychology, art, anthropology, politics, music, dance, costume, customs. Books in French, German, and Italian (Lee taught himself all three as a child). He even had books in languages he couldn’t read—such as Japanese—and translators who made house calls when he felt like learning them. “God, has he actually read all these?” Marilyn exclaimed, visibly impressed. “These damned books,” Paula grimaced. “We’ll have the greatest library in the world, and starve to death!”

Marilyn nestled on the floor next to the mirrored fireplace wall as Lee bombarded her with questions: Who was the actress she most admired? (Eleonora Duse.) Which poets did she love most? (Whitman, Dickinson.) Was she interested in psychology? (Yes!) He wanted to get to the white hot core of things, just like Marilyn did.

Susie followed Marilyn into the kitchen and found her scanning Paula’s little shelf of books on tarot, diet, astrology, and Catholic metaphysics. Much to Susie’s surprise, Marilyn asked about her acting career—what parts had she done since they’d met in California? Oh, and did Susie know they were both Geminis? Paula beamed from her station at the sink, silently plunging dishes into soapy water.

Just then, Susie remembered something Marilyn had told her the previous year in California. “I really admire your father,” Marilyn whispered, her lips hot and close to Susie’s ear. “I’m going to come to New York and study acting with him. It’s what I want to do more than anything.”