As its dismantle theory becomes reality, Critical Resistance works with its coalition partners on change and build. The majority of the facilities they propose prioritizing for closure are in California’s Central Valley, towns populated by individuals as politically conservative as the Bay Area is politically liberal. Since CR’s California chapters are located in the more progressive cities of Los Angeles and Oakland, its staff collaborates with organizations that have daily contact with locals in the state’s central region. These local partners serve as conduits between the needs of the community and decisions being made by the coalition. In town hall settings, they will listen to residents’ concerns and promote community-oriented avenues of investment—using the cost of imprisonment to develop mental health services, increase wages for local workers, ameliorate education systems, and so on. This “common-sense resource allocation,” as organizers term it, rethinks public safety by focusing on community needs rather than punitive retaliation.

“We’re building power in coalitions, in our campaigns, to get material wins by taking power away from the PIC and putting that self-determination and agency back into the community,” Viju said. “We’re part of different local grassroots efforts to figure out what the needs of the community are, how we can help, and how we can plug in to make prison closure in that place a reality.”

Abolition by Default

You’ve read a little about the prison-industrial complex in chapter 2 and how all prisons have some form of penal labor, but the presence of a widescale profiting mechanism within the California prison system is especially acute. There are 70 factories in California’s 33 prisons. Between 2014 and 2015, these facilities earned $207 million in revenue, or $58 million in profit from the labor of incarcerated workers, either by offsetting costs for prison maintenance, selling prison-manufactured goods, or contracting with private companies.19 Some 7,000 incarcerated workers are overseen by the California Prison Industry Authority, a state agency, which uses prison labor to manufacture everything from US flags, license plates, and packaged candy to office furniture for various state buildings and schools.20

These “jobs” are not voluntary. Curtis Howard, a founding member of All of Us or None San Diego, said he rebelled against work assignments, haunted by his “ancestral lineage,” and was penalized with time added to his already lengthy sentence. The labor cannot even qualify as rehabilitation or reentry efforts because many equivalent positions on the outside require state licenses—licenses the state denies to individuals with conviction histories.

“In California alone, [economists Morris Kleiner and Evgeny Vorotnikov] estimate that licensure has eliminated almost 196,000 jobs, has resulted in $840.4 million in lost annual output, and has created a $22.1 billion annual misallocation of resources,” Matthew Mitchell, an economist and senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, told the California Senate Standing Committee on Business, Professions, and Economic Development in 2019. “By their estimates, California’s licensing regime is costlier than that of any other state in the nation.”21

Unsurprisingly, the Prison Industry Authority’s biggest customer is the prison system itself, accounting for about two-thirds of sales. All the furniture in Ivan Kilgore’s cell, for example, is stamped with “PIA.” And while the PIA does partner with the private sector (see p. 24), the majority of the prison “workforce”—about 95 percent—hold prison maintenance jobs, such as laundry, food prep, and janitorial duties. In buying materials produced by the cheap labor it forces upon its population, and by creating workforces around maintenance, the prison department offsets the majority of its operating costs, allowing administrators and staff to line their pockets with the remainder. Consequently, prison guards in California receive a higher base salary than their counterparts in any other jurisdiction, including the Federal Bureau of Prisons.

“Because of the extent to which prison building and operation began to attract vast amounts of capital—from the construction industry to food and health care provision—in a way that recalled the emergence of the military industrial complex, we began to refer to a ‘prison industrial complex,’” Angela Davis wrote in her 2003 book Are Prisons Obsolete?.22

For most of the twenty-first century, progressive politics has erred on the side of reform when it comes to combating the prison-industrial complex. Electronic monitoring, for example, was considered a preferable alternative to incarceration. Instead, electronic monitoring, like the anklet that bankrupted Ali, has allowed law enforcement to extend imprisonment beyond prisons and jails. The devices also serve to generate further profits for the prison-industrial complex, with large-scale use of monitors like “the Guardian” being sold by ViaPath Technologies (formerly Global Tel Link, or GTL), the sole provider of phone services to prisons and jails in the state. In this way, rather than curbing the continued growth of American incarceration, reform has allowed it to evolve; the prison-industrial complex continues to scale up and turn profits far beyond prison walls.

CR makes an argument for abolition by default, highlighting the fact that prisons were originally established as a more humane punishment than death. Not only do we continue to perform state-sponsored executions, a method even Jonas Hanway and his contemporaries three centuries ago considered to be archaic, but innovations such as indefinite solitary confinement and twenty-three-hour lockdowns have served to make the system more expansive and more oppressive.

“What was once regarded as progressive and even revolutionary represents today the marriage of technological superiority and political backwardness,” Angela Davis writes. “No one—not even the most ardent defenders of the supermax—would try to argue today that absolute segregation, including sensory deprivation, is restorative and healing.”23

Critical Resistance’s founders have looked at the various evolutions and reforms of the prison system, including the rise of the prison-industrial complex, and have implemented organizing techniques that fight the beast without setting off a rash of snakeheads. Part of the political education that new organizers receive, for example, is a word of caution about carve-outs—caveats that preclude prisoners of certain offenses from various legislative reforms—and exception clauses. After all, it is the exception clause in the 13th Amendment that allows the prison-industrial complex to generate profits off slave labor. This means moving away from propositions that focus on “nonviolent offenders” and toward more-inclusive demands.

“We’re not going to divide who we’re calling for freedom for,” Isa explained. “We know that when you only call for the freedom of people with certain types of offenses, you’re actually building a brick wall that makes it that much harder for us to be able to dismantle when we go back for the rest of our folks.”

Stuff in the Margins

In Defund Fear, Zach Norris uses his own experience of having his home broken into to examine alternatives to punishment and possible alternatives to crime prevention. At the beginning of the book, he unpacks the moment he came home to find the windows of his daughters’ room shattered.

“The true threat in this story was not the would-be burglary, but the stuff in the margins—a fragmented healthcare system with a racial bias, the radical wealth inequality that causes widespread poverty. Both are the calculated outcomes of a system that prioritizes profit over humanity, for the benefit of a powerful few.”24

Organizers do not think of abolition as a destructive practice. Rather, prison dismantlement is a means to opening up space—both physical space and in states’ budgets—to build something new. Instead of prioritizing profits over humanity, it reallocates prison-industrial profits into those “stuff in the margins.”

“Even with the warm shutdown [of Deuel Vocational Institution], there’s a savings of $110,000,” Viju explained. “That’s $110,000 for public schools in Tracy.”

At the time of this writing, California is on the brink of closing its second prison, the California Correctional Center in Susanville, which was profiled by the New York Times. A February 2023 report from the Legislative Analyst’s Office said the state can close up to nine additional prisons while still complying with a federal court order that dictates each facility’s maximum capacity.25 With the three prisons already slated for closure, the coalition may exceed its goal, as twelve prisons are now identified for closure by the state’s own analysis.

This analysis, of course, is based purely on numbers: The state prison population had dropped from its peak in 2006 of 165,000 to 95,000 in 2023. There are also budgetary numbers: The state’s operating cost for its prisons is $18 billion annually.26

“Difficult decisions have to be made,” said Caitlin O’Neil, one of the report’s authors. “But if we don’t make those decisions, the alternative is paying hundreds of millions for prison beds we don’t need to be paying for.”27

This viewpoint is, of course, strategically sound: If anything can sway more conservative members of the state legislature—and the general public, for that matter—it would be fiscal responsibility. But there’s a more community-based element that can appeal to voters.

“The way we get [to abolition] is by changing the narrative and changing people’s understanding of what we need to keep us safe,” said Viju. “We don’t actually need more cops or more prisons in the community. What we need is housing, healthcare, education, and things like that. As we shift away from the PIC, we’re putting those funds or those resources toward those institutions.”

In September 2022, Lassen County Judge Robert F. Moody ruled against a preliminary injunction to stall shutdown efforts in Susanville, citing the fiscal imprudence of the state’s prison maintenance.28 A few months later, the corrections department announced it would not renew its lease with CoreCivic for California City Correctional Facility, terminating the contract in March 2024 and adding a fourth facility to its list of confirmed closures.29 In Tracy the warm shutdown provoked CURB to draw up a Prison Closure Roadmap. Published in February 2023, it details how the state can safely shut down prisons completely, without repurposing them or having them continue to drain resources.30

With town halls and community meetings underway in prison towns across the state, the opportunities for what comes next are vast. And while there is an urge to demand an immediate solution, abolitionists such as Mariame Kaba believe the urge to at least imagine beyond incarceration is far greater.

“When you say, ‘What would we do without prisons?’ what you are really saying is: ‘What would we do without civil death, exploitation, and state-sanctioned violence?’” Kaba said in her bestselling book We Do This ‘Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice. “That is an old question and the answer remains the same: whatever it takes to build a society that does not continuously rearrange the trappings of annihilation and bondage while calling itself ‘free.’”31

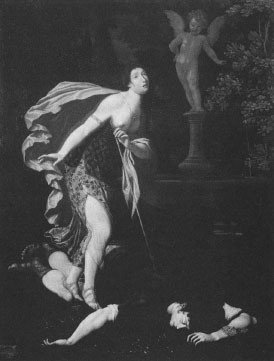

Bigger than Life by Scotty Scott aka Scott W. Smith

5

Reimagining Capitalism:

Greenwood

On a brisk December morning in 2022, Democratic Senate candidate Raphael G. Warnock walked into the SWAG Shop, a barbershop in Atlanta’s west side. He casually sat down on one of the red, cushioned chairs and sank in.

Warnock was not at the SWAG Shop for a shave or a cut. He was there to make one final appeal to voters who would be heading to the polls the following day for the Georgia Senate runoff election. Seated beside him was the shop’s owner, Mike Render, a rapper better known as Killer Mike.

“The barbershop is . . . a social center, especially in African American communities, where you find out who did what,” Mike told the crowd of constituents and media personnel. “I’ve been terribly impressed by this man as a human being, as a member of the clergy, and as a politician. I am here today to give a shot to him so that we may all give an ear to him. We should get out to the polls.”1

The fact that Warnock’s final day of campaigning began at the SWAG Shop speaks to Killer Mike’s influence on the culture beyond his artistic endeavors. Known primarily for his role in the rap duo Run the Jewels, Mike has used his success in the music business to fund several enterprises in Atlanta. He opened the SWAG Shop in 2011 with his wife, Shana, adorning it with black, red, and yellow decor. The storefront illuminates the sidewalk on Edgewood Avenue, with an all-red finish, black tinted windows, and a yellow stamp logo featuring the shop’s name. A black shingle hangs above the entrance with The SWAG Shop written in yellow type. On a day when the shop is filled with patrons, not politicians, the soft hum of electric trimmers radiates from the cushioned chairs. Black floors. Yellow letters. Red chairs.

The color scheme has become something of a trademark of Mike’s various businesses. In 2018 he bought Bankhead Seafood, a fifty-five-year-old restaurant he had frequented as a child, with rapper T. I. and developer Noel Khalil.2 While the brick-and-mortar restaurant is still under redevelopment, a Bankhead food truck draws in crowds. Block yellow letters spelling out Bankhead Seafood encircle a silhouette of a red, scaly fish standing in stark contrast to the all-black truck body. Black truck. Yellow letters. Red fish.

The colors suit him: Black and red are staples of the city he adores, with three professional sports teams—the Falcons (NFL), Atlanta United (MLS), and the Hawks (NBA)—all represented by black and red logos. But they are also “power colors,” demanding attention, as Mike himself often does when it comes to the issues impacting his community locally as a Black man in Atlanta and nationally as a Black man in America.

“I don’t give a shit about liking you or you liking me,” he told GQ magazine in the summer of 2020. “What I give a shit about is if your policies are going to benefit me and my community in a way that will help us get a leg up in America.”3

Atlanta is a city bursting with color, with street art serving as a trademark of the city walls. Not too far from the SWAG Shop is the heavily trafficked tapestry of the Beltline, the city’s main railway. The dim lighting of lamp posts creates an angelic hue around the depiction of a young girl in a blue dress imprinted on the walls. The child, a representation of Carrie Steele, who founded the city’s first orphanage for children of color, stands among waves of orange and blue, peppered with small, black symbols that look like miniature parachutes. Nearby a neon-green frog seemingly pops out of the wall, with wide, fiery eyes and reddish-orange webbing. Aquamarine silhouettes and yellow graffiti tags add to the cacophony of color emanating from the cavernous underbelly of the mass transit system. Red storefronts. Neon frogs. Orange waves.

But, according to the local #BankBlack movement, one color trumps them all: Green.