I was unused to praise. Who wants haunting, wrenching, and honest in the middle of a war?

Those who know it.

But I didn’t. I didn’t know any of it beyond what I saw in the corridors of the hospital. Those soldiers brought a memory of the trenches home with them, to carry around always.

Clare, I know a gallery, in Paris. The owner is an old friend. May I send one to him?

I thought and, with a hesitant pen, wrote, Yes.

The first one we sent, it sold right away. “A soldier, recently returned from the Front,” said Monsieur Santi, the gallery owner. The next two sold just as quickly. “You have an admirer,” he said, and asked me to send more.

Checks came to me in Glasgow, checks I held in disbelieving fists, then tucked away in the bottom of my washstand drawer. Share them with the world, Finlay had said. I hadn’t expected compensation for that.

I wrote to my grandfather at Fairbridge. I’ve done it. Like Grandmother, I’m an artist now.

When a letter came for me, it wasn’t from Perthshire. This envelope came from Paris. The stationery bore the insignia of the American Red Cross.

Studio for Portrait Masks

70 bis Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs

Paris

January 1918

Dear Miss Ross,

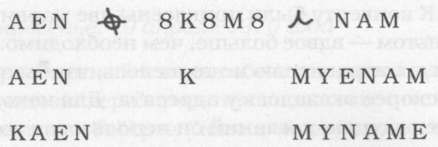

My name is Anna Coleman Ladd and, under the auspices of the American Red Cross, I am attempting to set up a studio in Paris modeled after Lieutenant Francis Derwent Wood’s Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department at the Third London General Hospital, Wandsworth. I am not sure if you’ve read about Lt. Wood’s work with mutilated English soldiers, though you may have heard of his department, popularly called the “Tin Noses Shop.” Like yourself, Lt. Wood is an artist, and he has lectured at the Glasgow School of Art, so you may be familiar with him. He has pioneered a new and quite astonishing technique of casting thin metal masks that are light, comfortable, and quite lifelike. Not medicine, but rather art.

These masks can cover the whole face, depending on the degree of injury, or can cover only part of the face. Glass eyes can be added with durable lashes made of thin strips of painted metal. For masks that cover one’s mouth, an opening can be left for a cigarette. These masks are seamless. It is quite an impressive feat, to make masks delicate and thinner than a lady’s visiting card, yet conveying so much humanity in those few ounces of metal.

I have learned his technique and, with the Red Cross, am setting up a studio here in Paris to help French soldiers in similar circumstances (called here mutilés). I’ve made some adjustments to the process—enamel paint offers more lifelike tones of color—but follow Lt. Wood’s general method in sketching, casting, sculpting, hammering, and finally electroplating the copper mask.

I have been looking for artists who pay great attention to life detail and who have the compassion to work amongst disfigured soldiers. I have seen your pencil drawings in La Galerie Porte d’Or and, Miss Ross, I believe you have both qualities.

I will be in London next Tuesday. Would you do me the honor of meeting with me? I would like to speak to you more about the opportunity to assist me in my work. Helping these soldiers is such a small thing for us to do, but for them, it is anything but small.

Sincerely, etc.

These days it was hard to feel like art mattered. When men were giving themselves, giving their youth, giving their life, when women were waiting and praying, I was painting. I was sculpting and drawing and creating, as though there wasn’t a war, as though my creation could counter all of that destruction. None of what I was doing signified outside of the art school. Anna Coleman Ladd was doing something that did.

I remembered the soldier I used to see waiting in the hospital, self-conscious with his ill-fitting rubber nose. If he’d had the chance to instead wear a work of art, would it change things for him? Would his world seem a fraction less dim?

“You’re meant to do this, Clare,” Finlay said. “You’re more than an artist. You’re a warrior.”

“You’re the one who’s been to battle,” I pointed out.

“And you’re the one who’s saved me.” He kissed me on the forehead. “Now, go. Go bring another man back to himself.”

The soldier stood in the threshold of the Studio for Portrait Masks. The room was bright, but he kept to the shadows.

Mrs. Ladd tried to keep the soldiers at ease and the studio cheerful. The phonograph in the corner, the sun-streaked windows and skylights, the little vases of peonies tucked here and there, warmed the room. Posters and flags were tacked between the windows—a large American flag, for her, and smaller British and French flags, for the rest of us working in the studio. It was a bright spot in an otherwise somber city. Three months after the war ended, Paris was still recovering.

Usually, the soldiers sat in little groups, laughing, smoking, playing checkers and drinking wine. Some were waiting for appointments. Others had nowhere else to go. Since being demobilized, too many lived on the streets. They begged for food, drink, a place to warm up. Here, at least for part of the day, they had all three. But, more than that, here they found people who understood. They found other soldiers just as broken.

This new one, though, he came alone, lurking in the shadows of the hall, not quite stepping into the room. They all did on their first visit. Once fearless in the face of a trench wall, they were now afraid to even step in the light. Light revealed what had become of their dreams of glory.

“May I help you?” I asked in French. Not Parisian French, but the French I’d learned in Africa, tinged with the warm, open sounds of Arabic.

He didn’t answer. The way he kept tugging on the brim of his calot, keeping a hand near his face, the way he kept his head down—he was a man used to shadows.

I couldn’t see his face, but it had to be shattered. Here, they all were. These soldiers who came to the studio, they were missing ears, eyes, parts of their faces. More than that, they were missing parts of their souls.

“Are you here for a mask?” Behind me, sculptors bustled about with plasticine and brushes and tins of enamel paint. A soldier lay back with his head resting on a table as Mrs. Ladd carefully coated his face with white plaster. Another stood in front of the mirror, looking, for the first time, at the copper mask covering the ruined half of his face. “Let me show you our work.” The phonograph played “La Madelon.”

He shook his head. One hand still hovered near his face, but the other, pressed against his leg, had relaxed. In the room behind me, someone had begun singing.

Through the shadows, nothing but horizon blue and the pale oval of a face. So many of the soldiers who came in had worn their injuries for so long they had the old uniforms, those dark blue tunics and bright garance red trousers. France was still trying to live down that mistake. After losing hundreds of thousands of troops in the first months of the war, they thankfully replaced the garance with horizon blue. This soldier, though, he wasn’t in red. He’d been in the war longer than many.

On his left arm, three chevrons bore that up, indicating three years’ service, and on his right, another for each occasion he was wounded. Only one on that arm. Three years faithfully served and then, in return, one injury for him to carry the rest of his days.

“You don’t have to stay, but won’t you please come in? At least for a few moments?” I tightened my shawl, dark and swirling like smoke. I’d traded it for a still-damp watercolor in Algiers. “Warm up with a cup of tea. I can show you my sketches of the other guests we’ve had.”

He cleared his throat. “You sketch?” His eyes shone in the dimness. “Ah, there’s charcoal on your fingertips.”