They ate lukewarm scrambled eggs and flavorless wheat toast at a diner a few blocks down the road, and when they came back John was pulling into the motel lot in a rented hatchback. He heaved himself up out of the driver’s seat, waving at them. He was huge, big and solid in jeans and a bomber jacket, his brown hair grown out in waves. When he folded Shelby into a crushing embrace she could feel the thick cables of muscle shifting under his soft exterior. The three of them chatted for a while about his shitty adjunct job, about Jo’s girl trouble and Shelby’s latest grueling animation gig, which consisted mostly of drawing a single sword fight over and over until she wanted to rip the stupid katana out of the ninja-maiden’s hand and behead whoever’d done the storyboards. Light things. Small. They weren’t ready to touch it yet.

Lara was next, arriving by cab and stepping out neatly onto the sidewalk, her long salmon dress swishing around her slender ankles, her big, round sunglasses reflecting the motel’s unlit neon sign and the chain-link fence around the pool. She looked like a movie star with her little peach-colored rolling suitcase and broad-brimmed sun hat. Some of her smiles were fake and some of them were real and on the first finger of her right hand she wore a platinum band set with what looked like real diamonds. It was funny that out of all of them she was the only one who had money. Shelby assumed it was from escorting, because if it had been movies or singing or any of the other careers she’d tried on and discarded with such restless impatience in California, she’d never shut up about it.

Mal came just before dark, meeting the rest of them in the same sleepy diner where Shelby and Jo had eaten breakfast. Lara had told her a while back that Mal and John had broken up badly, and the look on John’s face as the door swung shut behind them agreed. It had been longer than that since Shelby had seen either of them. Mal looked good, but tired. Estrogen agreed with them and they’d finally put on a little weight. Their hips were padded, the shadow of a double chin under their pointy jaw. They wore tight black jeans and a graying hoodie over a thin, ragged tank top. They smiled and Shelby felt them lie about how good things were with their partner Charlie, a leaden, heavy lie straight from the gut, and then they were all ordering from a hard-faced waitress in an apron and a faded peach-colored uniform, the table filling up with wilted salads and burnt hamburgers. They had already started eating, Lara only picking listlessly at her greens, when the bell over the front door tinkled and Felix walked into the diner.

He looked so different from the last time Shelby had seen him, six or seven years ago at Lara’s going-away party, right before she moved out to the East Coast. His hair was thinning. His shoulders were a little hunched, and he had the beginnings of a potbelly. In his Wranglers and leather jacket, scuffed work boots with broken laces on his feet, he looked like someone’s contractor uncle who made book on the side. For a heart-twisting moment she almost thought Nadine might walk in after him, not the girl she’d known but a woman, tall and strong and beautiful with a throaty voice and waves of sandy hair that stank of cigarettes and grease.

It came to Shelby then just how insane this was, just how little sense it made for five broke queers straggling one by one out of their twenties—and one rich bitch, same—to drop everything and race to Reno fucking Nevada on the say-so of their disturbed foster sibling who lived in his car. Only Lara could really afford to travel like this. The rest of them were blowing rent money, or had blown it already. And for what? A story that had been true, once, until a thousand, thousand tellings and retellings rendered it a soup of resentment and grief and hormones. A thing that had seemed like the end of the world until life in its wake kept unfolding with its relentless, monotonous procession of bills and work and dates and oil changes, until years of dodging truant officers and landlords and the dead-eyed drones from California’s child and family services department left it lumped alongside the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the subprime mortgage crisis and the opioid epidemic and penal slavery and every other miserable thing you had to ram into the back of your mind to get out of bed in the morning and push yourself through another day emptying grease traps. Who were they to think they could take this thing on, much less beat it?

Felix pulled out the last chair at the little round table. It was dark outside and their reflections swam in the water-spotted glass of the diner’s storefront, haloed in light. They were silent. It stretched on until Mal leaned toward Felix, cleared their throat, and said gravely: “Freddie Mercury’s corpse called. It wants its mustache back.”

John looked at the pictures Felix had given him, a folder full of four-by-six glossies, a few blown-up printouts of digital photographs—all of a compound not too different from the one he remembered, except that the cabins all had shitty vinyl siding and the main house—if that’s what it was—stood much closer to the camp, just outside the chain-link fence on a rocky ridge maybe fifteen or twenty feet high. Even in the grainy image John could see greenery pushing its way through lifeless soil and between piled stones. It had bothered him ever since that summer. What made it grow like that in the middle of a desert? Whenever he thought about it he would always come back to a single awful thought: it must be bodies. All those little corpses, their copies already cleaned and pressed and sent marching off into the world, mulched and buried, nutrients seeping into the earth.

There were people in some of the pictures. Mostly kids, but he recognized Dave, new lines at the corners of his mouth and eyes, hair a little thinner, maybe, leading a line of boys across open ground into the desert. A few other counselors looked familiar. He’d had dreams about Garth for years after Camp Resolution, sometimes that the older man was chasing him through the burning maze of the farmhouse, sometimes that they were twined together, sweating and grunting, Garth whispering something in his ear in a language he couldn’t understand, but there was no sign of him in Felix’s pictures. It had happened. John and the others had killed him. There was Marianne, the woman Nadine had bitten, looking older and a little heavier.

Mal’s phone kept buzzing. John had been trying not to look at them, not to notice when they looked at him in turn. It had been so bad between them, at the end. He recognized the way they were looking at that glowing screen, the desperate, twitching hunger etched into their face as their thumbs danced over the keypad. Someone back at home was tugging on the umbilical cord they’d never quite managed to shed, even without their mother hanging on its other end.

That’s not your problem anymore. They can be fucked up with whoever they want.

He wondered, as he thumbed through a second sheaf of pictures, noting sticky, hairy pellets and stands of something like bamboo pushing their way up through the rocky soil, what Louise was doing now. She hadn’t called. She hadn’t texted. He’d left her half a dozen messages but by now she was probably with her parents telling them he’d had a breakdown, that he’d fled the apartment after babbling about his alien abduction. He’d gotten Steph—a friend of theirs—to agree to feed the cats for a few days until he and Louise could figure something out.

It’s over.

It had been a kind of joke, really. One of those long, pointless, rambling jokes Mal used to love to tell, fifteen minutes of setup for the corniest punchline imaginable. Some pun that made them all groan and throw things at him. A fat little faggot, some transsexuals, and a couple of other gays get sent to a conversion camp—stop me if you’ve heard this one. Fifteen years of borrowed time spinning their wheels in dead-end jobs, flaming out one by one, over and over, and now it was pulling them back in. They’d never left that basement. Nadine was still burning.

Felix was talking, answering a question Lara had asked. “You remember how they drew our blood right after they brought us to the house?” he said. “How they kept us waiting before bringing us down to it? I think they were worried we might get it sick, or that one of us might be on something that could fuck it up if it got into its system. They drugged us, then gave us a drug test. It doesn’t make a lot of sense, right?”

Pictures of red curtains in the windows of another sleepy desert town. Armed guards in scuffed denim on the wraparound porch of a half-built farmhouse. Men on horseback leading kids through the wasteland. He could almost feel his blisters reopening. Mal’s phone buzzed again. They looked so tired in the screen’s blue light.

“They’re testing for club drugs. Ecstasy, ketamine, molly.” He smoothed a sheaf of stained and crumpled papers that looked to have been shredded and then taped together out among the plates and coffee mugs, flattening the crinkling mess with his palm. “I found these in their garbage. Whatever it is, I don’t think it likes getting high, at least not in a very particular way.”

Lara looked skeptical. “Then why did they drug us? That night, with the mushrooms or whatever they were.”

“I only have guesses,” said Felix, “but I think it was to get us ready to be copied. To soften us up, open our minds.”

Jo broke the silence. “So your plan is what, we lure it onto Willie Nelson’s tour bus and hotbox it?”

“No. My plan is we hook up with a dealer I know in Vegas and we buy him out of all the ketamine he’s got, then we find that fucking thing and send it on the trip of a lifetime.”

John cleared his throat. “How are we gonna buy this guy of yours out, exactly? I teach fiction writing at a community college; I’m going to be paying off my plane ticket for like four months as it is. I probably have about a hundred and seventy dollars in my checking account.”

“Lara has money,” said Felix.

“Oh, help yourself,” Lara snapped.

We could tell the governor, thought John. We could tell the police. We could tell child services. They weren’t real thoughts. They’d had each one of those conversations a thousand times in their youth. No one cared about a little reform farm for faggots. No one gave a shit what good, honest ranchers did to the sissies and dykes and the rest of the freaks. Fix them or fuck them, kill them or cure them—as long as it was quiet, who cared? And beneath that, a darker thought: that it might already be entrenched in those same institutions. They had no way of knowing how many it had infected, how far its influence spread.

“You’re the only one of us who can afford it.”

“So? Who says I’m going to bankroll you? Why the fuck is this my responsibility?”

“Lower your voice. The waitress is looking at us.”

“Oh, I’m so sorry, snake. Think you can salvage the op?”

“None of this matters,” said Shelby. The rest of them shut up. They’d always liked her best, back when they’d lived together. She had a kind of indefinable mommy-ness to her, a sense that if you cried in front of her she’d rest your head on her breasts and stroke your hair. Maybe it was just that she was pretty and fat and patient and had big, sad eyes, or that after Nadine they’d all made a point of loving her a little more than they loved one another. Whatever the reason, they listened.

“How are we going to get close to that thing?”

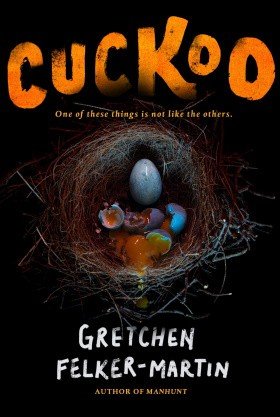

The first time Lara had been sectioned it was for telling her therapist about waking up beside her half-formed twin in the basement of that farmhouse, and the things she dreamed as she slept beside it. The meteor of flesh and bone. The false bird chirping in its nest. The Cuckoo, stealer of faces and skin.

Reciting that little stream-of-consciousness epic to one Dr. Bethany Weaver had earned her a night on a locked ward which became, after she spat on a nurse for refusing to use her real name, two weeks of isolated observation. The funny thing was that she’d seen it coming, had felt the tide of Dr. Weaver’s confidence in her recede like the ocean did before a tsunami. She’d kept talking anyway. That had been her first time hooked on Klonopin, skin crawling, fried and anxious, desperate to drag that soothing benzo blanket over her thoughts, to deaden things enough that she could make it through another night. Looking into the trunk of Felix’s Impala, she felt the old itch again for the first time in years.

The upholstered floor of the trunk was covered with guns, all secured with strips of Velcro. A hunting rifle, three holstered revolvers and a pair of plain black automatics, a shotgun with its stock and barrels filed short like in a mob movie, and a long, mean-looking thing with a wooden stock Jo thought might be a Kalashnikov or AK-47 or whatever they were called. There was ammunition, too. Boxes of it, and metal cases fastened with heavy clasps. Walkie-talkies and a first aid kit. Road flares. Grenades. It reminded Lara of that sad, lonely bunker in the desert, and the man lying dead in its shower.

“Jesus, Felix,” said John. He sounded faint.

Felix shut the trunk and locked it.

“And what if the drugs don’t work?” asked Mal. They sounded a little hysterical, their voice tight and frantic. “What if it just gets sick or wigged out and then shakes it off?”

“We’re going to need to test it,” said Felix, scratching his chin. The parking lot lights buzzed dully overhead, moths and other insects circling around their glow. “I thought we could use one of the replacements. The doubles.”

Lara spoke without thinking, her voice coming as though from a long way away as she thought of a house on the edge of the woods and a hide-a-key under a rotten old porch and a little boy who had played there in the years when his dog was his only friend.

“I know where to find one.”

XIX LAYLA