XVII CAPGRAS DELUSION

Boston, Massachusetts

Lara lit another cigarette from the glowing butt of her last, then sucked in a final drag and flicked the nub under the tires of the cars whooshing through the rain past the departures gate at Logan. The overhang kept the worst of it off but the air was still damp and cold, clinging clammily to her skin. She hunched deeper into her coat, shivering as she exhaled and drew the coils of heavy blue smoke up into her nostrils, savoring the earthy burn before blowing it out again. The coat was Michael Kors, a gift from a longtime client, and it was absolute shit for Boston in late fall. The wind cut right through the marled sheepskin and its dark silk lining. She took another deep drag.

Lung cancer, here we come, she thought as she watched rainwater hiss through a sewer grate a few feet from where she stood. The butt, caught in the gutter’s current, swirled through the corroded iron and was lost to sight, borne down into the dark and out to—where? Boston Harbor? The Charles? Some scenic reservoir or wetland? Or maybe, some hateful corner of her brain suggested, it was Boston’s version of the farmhouse basement. Maybe it lurked just out of sight, sifting the rainwater that fell through the grate, searching for anything edible, for anything it could hollow out and imitate.

New England always made her think like this. It was the cold, the rain, the ceaseless fucking humidity. Akira dying didn’t help. He’d been kind to her, put up with her shit without so much as a raised voice, cooked for her night after night even knowing she’d just puke it up afterward. She closed her eyes and tapped her silver cigarette case against her hip. A gift from a client, a silver-haired old man named Rudy with a tan like a Ritz cracker and a dazzling white smile. He was waiting for her in Palm Springs, would be there to pick her up from the airport in his big silver Corvette, the top down and the light flashing in his sunglasses and from the band of his Rolex. They’d kiss, his cologne enveloping her in a cloud of heady musk, and she’d blow him while they did ninety on the highway, the Stones or Jefferson Airplane blasting from the Corvette’s speaker system loud enough that she could feel it in her bones. She’d straighten up after, fixing her lipstick as the wind blew through her hair, and he’d say something like “You’re a hell of a girl, Bunny,” before dropping her off at her hotel with an envelope and a promise to call her sometime that week.

It would be warm there. She’d have a room overlooking the lagoon. She’d lay out by the hotel pool, feeling like a movie star, watching men and women check her out in passing, feeling the outer edges of their lust the way she had since the summer of her fifteenth year. A trace of the wild power that had danced in her that summer, that had woken her screaming so many nights with fragments of the others’ dreams replaying on an endless loop lodged in her mind and made the psych ward such a deafening hell of overlapping want and misery and hatred. She always knew when someone wanted her.

“Think I could get one of those?” asked a man in a Red Sox sweatshirt and blue jeans. He’d sidled up on her left while she was lost in thought. He looked like money in spite of his getup. His nails were manicured, his haircut the kind of effortlessly rumpled waves only a three-hundred-dollar trip to the barber could produce. Finance bro, she decided. Probably dressed down for a long flight. She dug out a cigarette for him and handed him her lighter, which he flipped open and shut with expert precision before exhaling a stream of smoke.

“Thanks,” he said, smiling. He had a hungry look in his eyes. She could feel it pouring off him, that familiar impatient yearning. It always reminded her of a little dog yapping to be let out. Men like him didn’t really understand their money yet. They didn’t have Rudy’s comfortable largesse, or the cold, sharklike affect of a real executive who knew exactly what he wanted and how to take it. They were nervous, resentful, impulsive. Stupid.

Lara pocketed her lighter. “No problem.”

They smoked side by side for a while in silence, his scrutiny uncomfortable but bearable, but when she flicked her butt away in a shower of sparks and ashes, he raised a hand and touched two fingers to her forearm, like she was a waiter who’d ignored his signal.

“You’re Bunny Vixen.”

God, not again.

“No, sorry, you have me confused with someone else.”

“Come on, you don’t have to do that.” He flashed her a wide, bright grin that didn’t reach his eyes. “I’m a fan.”

She stepped smoothly away, shrugging off his hand. “I’m not working right now.” She turned to leave.

“Five thousand.”

He was smirking when she looked back at him. It made her want to kick a heel off and put the spike through his eye socket. “Excuse me?”

“Come back to my hotel room for half an hour. Have a little party with me. Five thousand dollars.”

“How about we go back to your car instead?” She stepped back toward him, resting a hand on his chest. She could feel the heat of his erection even in the chill. The musky funk of how badly he wanted her to do something little and mean and boring to him, something he thought was the apex of perversion. “I can jerk you off, wipe your cum on the upholstery, and then next week I’ll find you out at brunch, and I’ll come up to you and your wife and your kids while you’re eating eggs Benedict and say, ‘Fancy running into you here, Bill. What are the odds? Remember me, the tranny who gave you that handy in an airport parking garage?’”

He stared at her, his mouth hanging open, then seemed to find himself. His face went hard and tight. “Fuck you, cunt.”

“Yeah,” she sneered. “Fuck me.”

It felt good to leave him standing there, though her stomach roiled at turning her back on him. Men had hit her for less. Her only defense now was an affect she’d spent years cultivating from one of breathy vulnerability to a sort of steel-clad cuntiness with a spine of fuck-you money. She’d probably made more than the little shit last fiscal year anyway. Let him hit her; she’d take his beach house and slice off his balls in court.

Her phone started vibrating as she stepped through the sliding glass doors and into the echoing clamor of check-in. She took her sleek little iPhone out of her coat pocket, pushing her fogged-over glasses up onto her forehead to read the caller ID. She answered, but somehow her voice had dried up in her throat.

“Lara? Are you there?”

Her palms felt damp and clammy. She licked her lips. “Yes,” she said, her voice a strangled croak.

“I found it,” Felix said, and she knew what he meant, had never been able to bury the knowing of it even when it had eaten through her twenties like a cancer, had put her in a psych ward in Rhode Island and then, a few years later, another in upstate New York. The line crackled. “I’m just outside Reno. The Star Motel.”

She thought of Palm Springs, of lying poolside like a lizard in the sun, a mimosa close at hand and clients cuing up to smell her dirty panties, to suck her toes and drink her piss and beg her to step on their faces and put her cigarettes out on their nipples. Clamps and spankings and ball gags. It was the best job she’d ever had. The only thing she’d ever been good at.

“I’ll be there tomorrow.”

Clearlake, California

That first night, all of them crammed into a motel room in a Podunk town just across the Idaho border, Jo had told Oji what happened at Camp Resolution, switching back and forth between English and her broken Japanese until she was pretty sure she’d gotten it all out, had vomited the entire nightmare onto the dirty carpet. He took her hands and said, “I believe you.” She saw how it hurt him to mean it, how badly he wanted to tell her she must have hallucinated, must have misunderstood something while out of her mind on whatever the administrators had given them—probably mushrooms—but he hadn’t. He’d believed her, believed the whole insane mess of it.

For seven years he’d worked his fingers to the bone however and wherever he could to keep a roof over their heads. Technical drafting, night shifts at convenience stores, stocking shelves at Walmart, telemarketing for a company that sold steel wool and industrial solvents in bulk to factories. He’d done it all without complaint, just like he’d worked through the tantrums, the depressive episodes, the fights and breakups and suicide attempts, the anorexia and petty theft until one by one the others went off on their own. Until it was just the two of them.

For eight years after that he’d lived with her in her little third-floor apartment on Gate Street. It was during that time he’d told her about his marriage to her grandmother, about the matchmaker in Hokkaido who’d known the signs and led them to an understanding. He told her about the men he’d loved, showing her letters full of poetry by someone named Yoshi who he said had been the most beautiful man he ever saw, long black hair and a little mustache. Like Clark Gable. A few weeks after that, Oji had gotten his diagnosis. Cancer, hospice, and pneumonia, bam, bam, bam. Three months start to finish, and now, in the back of a cab, all that was left of him was the little copper urn in her lap, no bigger than a potted plant.

“… another tragic entry in what psychiatrists have termed an unprecedented case of mass hysteria. A Ventura County mother murders her teenage daughter in cold blood before turning her gun on herself. Friends and family say the deceased, forty-one, struggled with a rare disorder known as Capgras delusion, the persistent belief that a loved one has been replaced by an identical or near-identical copy. Police have thus far been unable to locate—”

The driver changed the station. “That’s all there is on the news these days,” he groused. “Mamas killing babies. They oughta do something about it.”

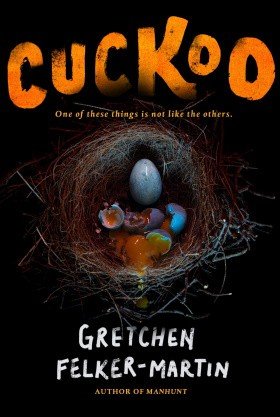

“They should,” Jo agreed. She always agreed with cab drivers, just like she always looked down when she passed by a cop. There was no way to know how far the Cuckoo’s work had spread. There was no way to know who was safe and who was just a glove of skin around a knot of alien muscle. Mostly she managed not to think about it. Mostly. The cabbie pulled up to the curb outside her building. “Thanks,” said Jo. She dug in her coat pocket for cash and handed it over without counting. Oji had always said it was bad character to count money in front of someone you were paying. She slipped out of the cab and shut the door, the urn cradled like a baby against her breast.

When she turned, the car pulling away, she found Shelby sitting on the steps of her walkup. For a moment the old fear seized her, the hair on the back of her neck standing on end, but if Shelby had been a copy she would surely have called ahead. She would have taken pains to make sure Jo felt comfortable. The fear passed. Shelby’s round face was flushed in the unseasonable chill. She flashed a sad smile. “Lara told me,” she said. “I tried to get here for the funeral, but you know what LAX is like. I’m so sorry, Jo.”

A cold gust blew down Gate Street, past the little pizza parlor—which was terrible, but the best you could reasonably hope to find this far from Jersey—and the head shop where Jo’s ex, Fiona, worked most days. It had been years since she’d seen Shelby. Christmas of 2009, she thought, when Lara had come out from Boston with that awful boyfriend, Max or Mack or something, who wouldn’t shut up about how Facebook was going to change the world. She took Shelby’s hand and pulled the other woman up and into a tight hug, and before she knew what was happening she was crying at her kitchen table while Shelby made coffee and rifled through the cupboards, making an unholy mess that would, Jo knew from experience, result in the best chocolate chip cookies she’d ever tasted.

“He was such an awful cook,” said Shelby, cracking an egg on the lip of one of Jo’s metal mixing bowls. “You remember his pancakes?”

Jo made a sound, half laughter and half sob, and rested her head in her hands. “Raw in the middle, burnt around the edges.”

It was strange, being together again. All through the end of high school they’d been caught in each other’s hair, trapped in a succession of tiny apartments and unable to stop seeing what had happened to them that one summer every time they caught sight of each other. She still felt it, even fifteen years later. Just a glimpse of the old scars on Shelby’s forearms and she was back in their blood-spattered bathroom keeping pressure on the wound and wishing she was anywhere else, even back home in the airless tomb of her parents’ house. It wasn’t that they hadn’t been close, it was that they’d never been able not to be. They were her family, and seeing them made her feel like she was drowning.