Mutilated monkey meat

Hairy pickled piggy feet

Jo groaned. Felix looked back with a grin. Behind Gabe, Shelby took up the uneven chant, yelling in something like harmony with Malcolm.

All comes rolling down the dusty, dirty street

And I forgot my spoon!

And then they were all singing it, belting it out loud enough that their voices pushed back the endless emptiness, loud enough to take the worst of the sting out of every step, to wash away the morning’s stupid arguments and scuffles and make them feel, if only for a little while, that the thing they’d left behind was nothing but a slimy lump, an overgrown Jabba the Hutt, and someday its voice would stop echoing in their heads and its memory would leak away, and they would feel clean again.

Great big globs of greasy, grimy gopher guts

Mutilated monkey meat

Hairy pickled piggy feet

As if to say, you’re nothing special, you Spencer’s Gifts–looking bitch. You dillhole. You’re just a sack of roadkill and old wigs. You’re a pound of hamburger somebody dropped on the carpet. They sang until their throats were raw, their shadows starting to dissolve into a deeper darkness, and even after the words trailed away Gabe felt lighter, more free. He was still smiling when his knees buckled, firecrackers of incoherent sensation going off in his head, and he dropped face-first into the dirt. Grit on his lips. Taste of blood. Then nothing.

Malcolm held Gabe’s head in his lap as the others clustered close around them. Gabe was breathing, but his pulse felt fluttery and weak when Malcolm pressed two fingers to his throat and his bruised eyelids twitched as though he was caught in some awful dream. He hadn’t stirred, not even when slapped and pinched. The sun was getting low.

“We’ll sleep here,” said Jo. Her whole face was peeling, right up to the hairline, and her dark hair was stiff with salt and dirt. She looked like shit. They all looked like shit, and now stupid anorexic Gabe—could boys even get anorexia?—was down and the rest of them wouldn’t be far behind.

Malcolm stroked Gabe’s hair for lack of a better idea. “It’s okay,” he murmured to the other boy. “You’re okay, baby.”

They ate in silence. The thought of drinking from the canteen made Malcolm want to hurl, even though his mouth felt like it had been packed with sawdust, so he waved it on. John broke out a gas lantern he’d found in the bunker and in silence they tried to find the most comfortable patches of dirt. Malcolm could just see the first stars coming out over the mountains, pinpricks of white in the bruise-purple sky.

The coyotes appeared not long after the sun had set. Three of them, waiting on their haunches outside the pale circle of lantern light. They were gangly things, no bigger than collies but with long, slim legs and pointed snouts. Their tongues hung from their grinning jaws and in the dark their eyes glowed flat and cold as coins. They’re waiting for us to die, thought Malcolm. He was tired enough that there was no drama to it, just an exhausted sense of resignation.

John sat down beside him. For a while they said nothing, Malcolm still stroking Gabe’s hair, the coyotes fading in the gathering dark until only the glow of their eyes and the gleam of light on spit-slicked teeth remained. A tight knot of anxiety formed in Malcolm’s chest as the silence stretched on and on. It was getting cold again, the icy chill of night in the open desert creeping back into his bones. Finally, John spoke.

“I like you,” said the other boy. Malcolm could practically hear him blushing. “Do you like me? I honestly can’t tell. If it was just the drugs, whatever they gave us, that’s fine. That’s okay. It’s just that I’d like to know.”

“You know there are literally scavengers waiting to, like, pick our carcasses clean right now,” said Malcolm. He didn’t like how snippy his voice sounded, how panicked and defensive. He sounded like his mother when someone pointed out she wasn’t making sense, or caught her in one of her lies.

“I know,” said John.

Malcolm thought of the other boy’s weight on top of him, of the feverish intensity with which his body had given itself up to John in the midst of whatever drug trip they’d been sent on. Part of him wanted to lunge back into those soft, strong arms, to spend however long he had left rubbing himself off against John’s thigh, but another part, one he didn’t fully understand, that spoke not in words but in the silent language of sidelong looks, knew that to be with John was to give up something precious, some indefinable cachet that everyone knew by sight without ever having heard its name spoken aloud. That same sense had driven him to mock the fat boy on their first day digging postholes for the fences, and it kept him silent now.

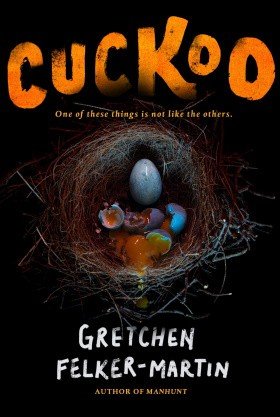

Something screamed in the distance, breaking the unpleasant stillness between them. Not the Cuckoo, but something like it. Some nasty little tumor, he thought, that must have wriggled loose from its vast bulk and slunk out after them across the plain. One of Jo’s dog-things. The coyotes fled at once, the glow of their eyes vanishing into the gathering dusk. He wondered if they knew to fear it from experience, if it had crept out here in the years before it found Mrs. Glover and snatched their pups, if it had given them sweet little replacements, balls of fluff with too-big paws, mischievous, panting grins, and cold, dead eyes like little chips of glass. Malcolm felt like his guts were full of ice water.

Jo bent and lifted the lantern. She had the shotgun in her other hand, its stock across the crook of her arm. “Can you move him?” Her voice trembled. Her pupils looked huge in the hissing white light. “John, can you carry him?”

John scrambled over and after a false start got his arms under the skinny boy and heaved him up into a fireman’s carry, then straightened with some effort. Malcolm tried to help, standing with him and supporting Gabe’s head where it lolled against the other boy’s back. The others were on their feet, too, pain and exhaustion forgotten. Something yelped out in the dark, whining and whimpering before it fell suddenly and totally silent. It sounded like one of the coyotes. Malcolm realized as he backed away from the sound that he’d pissed himself, urine soaking the crotch and leg of his jeans, and before shame he felt despair at wasting water.

A voice came from the darkness, high and desperate.

“Wait! Please, wait!”

They froze. Malcolm’s own breathing seemed suddenly thunderous. He knew that voice. It was Nadine’s.

“It’s a trick,” Felix whispered.

“Malcolm, take the light.” Jo shoved the hissing Coleman lantern at him. “I need both hands. Quick. Now.”

He took it, fumbling with the handle, his fingers half-numb in the cold, and Jo broke the shotgun, checked the barrels, and then closed and cocked it. Click, click. She brought it up to her shoulder. He wondered if he could get it from her, if he could shove both barrels in his mouth and still stretch to reach the trigger. That or run. Run. His whole body ached for it, but he was so tired, and the dark was so complete out here, even with the whole sky bathed in a bright sea of stars. He’d never seen anything like that in Connecticut.

“Okay,” said Jo. “Everyone, walk. Follow Felix.”

“Help me. Please, you guys. I’m hurt. My leg … there’s something wrong with my leg.” The voice trailed off into a thready sob. “Why won’t you wait for me?”

“Move,” Jo snapped. She started backing away from the voice and Malcolm stumbled forward just to keep ahead of her, the lantern’s light swinging wildly.

“Keep it steady,” said Jo, her voice terse and taut. “I think it’s the thing, the one I didn’t kill back at the bunker.”

“What if it’s her?” Shelby sobbed. “What if she’s alive?”

“Pleeeeeeeeeease.”

It sounded closer now.

“You saw the house,” said Felix. He had her by the arm and he was dragging her after him as John shuffled forward, bent under Gabe’s weight. “She’s dead. She was dead before it even blew. That thing ripped her apart. The roof caved in.”

“It hurts. Please, it hurts so bad. My leg…”

Close enough now that Malcolm thought he could hear the scratch of claws on rock and dirt, the soft weight of padded footfalls. He caught a whiff of something rancid, a septic reek mingled with something like the bright, bitter tang of grapefruit juice. He kept moving backward, trying not to think about whether anyone else knew he’d peed his pants. How long had it been since he’d wet the bed? Four years? Five? He’d lived in terror of sleepovers in middle school, when people had still invited him to sleepovers. He’d lain awake at night staring at the ceiling and willing himself not to pee, or sit hunched and miserable on the toilet, horribly certain that somehow there were just a few more treacherous drops to squeeze out.

“Help me. Shelby, is that you? Shelby? I love you. I love you. It’s the last thing I said before you left. Why did you leave me?”