When the thing that had been Cheryl came for her, she didn’t fight.

They met no one else on their way up and out of the crater, though both times Gabe paused to look back he saw silhouettes rushing through the dark, billowing clouds of smoke around the burning compound. He could still see snatches of the thing falling huge and awful from the sky, of the first tender bodies it had stolen to conceal itself. The white fire had burned deep into him, deeper than the drug trip, until it melted its way through the bedrock of his consciousness and dropped like a falling star into the mad pink void beneath, the place where skeletal women of pure light spun and danced in a tearing wind amid the sound of babies crying, where semen dripped from tubes of mashed and deformed lipstick and eyeliner ran down the cheeks of featureless faces veiled by rivers of dark hair and the plastic arms of Barbie dolls opened to receive him in a slender and jointless embrace.

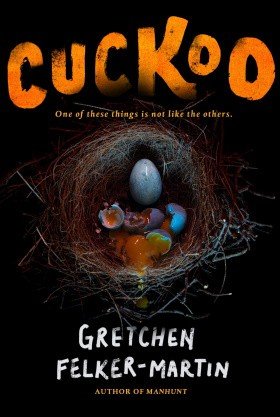

And then they’d come for him. His friends had dragged him out of that terrible room where the slimy, mewling newborn thing had made itself his double, kissing and licking his body, leaving slicks of mucus that dried into greenish crusts that now flaked away as he scratched at them. None of it seemed real. He’d helped Malcolm and John beat Garth, maybe kill him. The thing, the Cuckoo, boiling up the steps. Nadine.

He blinked rapidly to hold back his tears. He was dehydrated enough already. They’d drained the single canteen Jo had brought with her on her one-woman mission to blow the farmhouse to hell before they even reached the forest’s edge. Shelby had stopped screaming, at least. Now she trudged in silence beside John, eyes red and expression blank. Gabe tried again to think of something to say to her, but what could he say that would mean anything beside the awful fact that Nadine was dead, that the best and bravest and toughest of them was gone forever. If he closed his eyes he could still see the fire chewing at her thrashing outline. The blast had seared the image deep into his corneas, Nadine and the Cuckoo all one wild black tangle of convulsing meat.

It was getting toward afternoon, he thought. The sun was high and shadows were dwindling to murky little pools. His feet hurt. He’d had blisters his whole time at camp and it occurred to him that maybe he’d outgrown his sneakers, a thought that brought on a violent wave of disgust. Gabe imagined his feet stretching, growing, spreading wider as hair sprouted in wiry tufts from the knuckles of his toes. How long had it been since he’d shaved his legs? He could feel his leg hairs catching in the ventilated fabric of his shorts, but to look down would be to see his knobby knees, his ankles—ugly, undefined—and all the rest of it. So in silence he trooped after the others, scrambling up and down the banks of dry streambeds and crawling under fallen trees supported by their living fellows until at last, in the shade of a huge knotted pine somehow clinging to life, they collapsed by wordless mutual agreement to rest.

Gabe lay staring up through the pine’s branches, the sky just slits and pinholes of bright blue between the canopy of needles. When he closed his eyes he saw Nadine’s silhouette—the one he’d seen once through a gap in the fence around the shower, the one he’d coveted and felt so much inchoate rage toward—coming apart in the red tide of the explosion. Before the searing heat and light had forced his eyes tight shut, he’d seen part of her upper body strike the top of the door frame, the Cuckoo writhing in agony behind, withdrawing back into the basement as ton upon ton of wood and shingle plummeted down on its massive bulk.

Brady must have been down there, too. And Smith. It hurt to think of Candace, who had blushed so prettily when he’d smiled at her. He wondered when he’d be able to think of himself as a woman, when it would feel anything less than mortifying to think “she” instead of letting the leaden weight of “he” drop from his tongue. He thought of Courtney Love’s messy red lipstick and unwashed platinum hair, of her mint-green dress and Kurt’s hand on her pale, smooth shoulder.

After a while with only the sound of ragged breathing, John spoke. “How’d you do all that?” he asked hoarsely, looking at Jo. “The dynamite. Where did you even get any of it?”

“Malcolm’s bunker,” she said, leaning back against the tree’s thick trunk. Her face clouded. “Things … these things were chasing me, after the counselors took Brady. Like dogs. I was running. I was so tired, I’d been up a tree all night and my whole body was so stiff. I ran until I puked, and then somehow it was like my feet knew where to go, like someone was telling me the way. I think … whatever it was that thing was doing to us, the stuff it was putting in our heads, it must have opened us up to each other, because I knew exactly where that bunker was and how to get there. I got in just ahead of them. They couldn’t fit through the passage, the way in through the rocks.

“I found the dynamite and blew them up while they were trying to get through the tunnel. They were too big for it. I thought I was going to bring the whole thing down, or blow myself up too, but it worked. I think one of them got away, maybe. They were all tangled together; it was hard to tell. Anyway, my plan was just to blow the whole farm apart, and then while I was coming down into the crater I saw them pull in and take you into the house. I figured I had to get them to come running.”

“I told you all I wasn’t fuckin’ lying,” said Malcolm, sitting up and glaring indignantly at the rest of them. For a minute it seemed as though things would somehow snap back to normality, as though Nadine and Smith and Brady might come stumbling and giggling out from behind a nearby tree and they’d all cry together and feel somber about the kids who hadn’t made it, but they didn’t, of course. Gabe was starting to understand that nothing would ever feel normal again. He ran a fingertip along one of the scabbed-over cuts he’d gotten when the farmhouse’s windows exploded, a thin, clean line just above his right collarbone.

“What now?” asked Felix. His voice broke. “What the fuck are we going to do now?”

Shelby kept losing time. She would walk for a while, following Jo between and over the dead pines, down gullies and up the far embankments, and the ground would change like a reel switching in an old-fashioned movie theater. She heard something about a phone call and an atlas and a feed store in a place called Resolution, but that was just noise. It came and went. In between, in the moments when the world dissolved into a kind of black and rushing static, there was Nadine.

I love you, she had said, but what was there worth loving? She’d let herself be drawn out through the door, had left Nadine behind and stood there helpless while she died. Who could love something so weak and slow and stupid? That smile, almost a smirk. The freckles across that crooked nose, broken and badly set. The raccoon bruises under her eyes. Sometimes, when her thoughts wandered, she heard Nadine speak in the voice of the thing under the farmhouse, the thing that had whispered to Shelby in her dreams and in the room under the earth.

Why don’t you come and stay with me, Andrew? Why don’t you come back to the house and crawl down through the charred and splintered beams, the loose wiring, the sheafs of scorched and smoking insulation? Most of her pelvis is still in one piece down here. You could fuck it, Andy. You could shove that fat little worm in your pants right up into it, to keep her close. Hair in a locket. Did you love her or were you just jealous of her cunt? I can make it go away. I can kiss it better, Andy.

Come and kiss me. I’ve almost got her lips right.

They went single file down a narrow canyon, the walls closing in until it became a tunnel and Shelby had to shuffle along sideways. Loose earth rained down on her head. She heard John cursing behind her and couldn’t find it in her heart to look back or to help him. The thought of seeing his fat body wedged between the rocks made her insides curdle with self-loathing rage. If she’d been thin and strong, Nadine wouldn’t have needed to help her on the stairs, wouldn’t have been held up waiting for her, wouldn’t have trailed behind while the rest of them ran out the door.

There was blood on the canyon floor and walls and loose rock everywhere at the juncture where Jo must have killed the dog-things she’d told them about, but no sign of the bodies themselves. Maybe a surviving thing had dragged its packmates away to mourn them in private. Maybe it was crying over them right now, gnashing its mismatched teeth and shedding cloudy tears as conjunctival buildup gummed the folds and wrinkles of its muzzle. Would the Cuckoo cry for its dead offshoots, for its procurers and caretakers who had burned alive in the farmhouse? She knew it wasn’t dead. She didn’t know why she felt so certain, but she did. It had survived.

I hope Nadine hurt you, you fuckin’ wad of bubblegum and pubes. I hope you’re screaming right now, for yourself and all your little jellyfish-face babies.

Shelby came out into a little courtyard in front of the bunker’s open door. Roots crawled over the rock walls and the ceiling of the cave above. A thin humus of dry soil, fraying plastic bags, and fragrant pine needles lay underfoot. She followed Jo into the darkness of the entry tunnel. The back of her neck prickled at knowing she stood under who knew how many tons of earth and rock, but it was a distant fear. Little white moths fluttered through the air as fluorescent lights crackled to life in the great room past the tunnel and the airlock entrance, both its pressure doors long since rusted open. A strange sense of déjà vu as she looked around the common area. Pantry, bathroom, bedroom, she thought, marking each exit in turn. Like her certainty about the Cuckoo’s fate, the knowledge came from nowhere, but after everything was it really so strange? Maybe they were telepathic now, their minds frozen open like the bunker’s doors after weeks of that thing’s dreams and the drugs and their bizarre conditioning in Ms. Armitage’s lessons. She couldn’t make herself care.

Jo came back from the pantry with an armful of black plastic packets as the others sank down to the floor. Shelby took hers without enthusiasm. The thought of spooning food into her mouth made her want to vomit, and the water Jo brought them in a little tin pail with a dipper tasted like rotten leaves and metal. It felt good on her cracked lips, but what was the point? What was the point of any of it? While the others pored over a flaking and yellowed survey map, she slipped away into the bedroom and lay down on the frayed and rotting sheets of the old double bed, not much more than a moth-eaten mattress on a slab of concrete jutting from the wall. There was no light in the bedroom, only a sliver of pale blue cast by the common room’s fluorescents, and as she closed her aching eyes, the coarse texture of the sheets and the smell of dust and mold began to fade, crumbling away into sleep where something hot and soft and wet was waiting for her, strong hands on her shoulders, guiding her mouth down to taste the salt. The sea. The blood.

What’s your name? Nadine’s voice whispered in her ear. The close heat of a bathroom stall. Golden light pouring in through the high, narrow windows.

Shelby.

Jo dozed in Felix’s arms. They lay together on a folded wool blanket he’d found in the linen closet, a few ragged sheets pulled over them. They’d kissed for a while after the lights went down, but exhaustion had been stronger than desire. She kept thinking about Pastor Eddie’s face unfolding, about his huge frame thrashing in the grass after John had shot him. She’d felt nothing looking at the body. No, it was Celine who haunted her. Celine with her bulbous eyes and crooked buck teeth, who she’d watched hesitate, sick with guilt, before kicking Nadine, who’d stumbled across Jo while she was planting dynamite up on the crater’s second tier behind some rhubarb leaves and trying to figure out how long to cut the fuse. It had all happened so fast. Rolling through the rhubarb, the stalks crunching wetly under them, her hand clamped over Celine’s mouth as they wrestled over the clippers the other girl was carrying.

It had ended so quickly. She wasn’t quite sure how. The long scissor blades buried in the other girl’s throat and Jo kneeling astride her, hands over her mouth, until the jerking stopped. Had she cried then, as Celine’s last breath husked against her spit-slicked palms? She couldn’t remember. She’d almost forgotten to light the fuse before creeping away, low to the ground and moving fast but part of her wanting to run back and throw herself onto the dynamite where she’d left it half-buried in the rich black earth. The shock of detonation—not the sticks in the rhubarb patch, but two she’d left at the northeast corner of the barn—had slapped her to the ground like a giant’s hand and for a moment, rolling over to her back, she’d seen the plume of brown and red expanding to fill the whole sky, burning fragments of the barn borne up spinning with it, and thought that she was staring into Hell. Scraps of wood raining to the ground around her, trailing arcs of smoke across the sky.

Celine’s dead, flat eyes among the rustling leaves.

Shelby woke all at once. For a moment, before the day came rushing back, she had no idea where she was or why it was so dark, the air so dry and close. Her throat was parched. It hurt to breathe. Slowly, feeling her way through the blackness, she slipped out of bed and found the doorway to the common room. A cold wind slithered low around her ankles, blowing in through the open airlock. A line of moonlight lay aslant the room. Someone’s leg. A hand. By the door, stars swimming on its surface, the water pail. She picked her way with painstaking care across the forest of sleepers and knelt down to drink, savoring the stagnant water even though it numbed her teeth. Her clothes felt grimy, the tender skin under her belly rashy and inflamed. She drank another cupful and then turned, mouth aching with cold, to find John sitting up in the moonlight.

“What’s going on?” he asked, voice bleary. He looked beautiful half-lit in silver, his pale skin smooth, his soft, round shoulder and the spill of his belly somehow delicate. His stretch marks shone like rivers and she wondered how it was that she could hate her own so much when they were so tender and so otherworldly on him. She went to him slowly, on her hands and knees, and laid her palm against that quivering slope as he stared at her, not speaking. His big, dark eyes. She could feel things where she touched his skin, feel them the same way she’d heard the Cuckoo’s voice or seen the dreams the others stumbled through alongside her own, as though through a fluttering tear in the world. Nights spent starving in bed. Calories and supplements and the guilty hum of the refrigerator after midnight, the whole house dark and poised to pounce at the first creak of a floorboard, the first sticky hiss of an ice cream carton’s lid pulled up.

How many hours spent pulling the skin of his face taut over the bones beneath, imagining his features hard and definite, the cream and butter of him all sliced bloodlessly away in one ecstatic pass of the knife—the same knife she’d imagined kissing her own flesh so many nights as she lay staring at her ceiling, begging the universe that tomorrow she might wake up right, that it had all been just one long, sick joke and now she could leap free of the body in which they’d caged her, surplus flesh abandoned in a shapeless steaming heap—and they were kissing, his hands recreating the generous curve of her hip, the crease at her waist, the velvety heft of her tit.

If I’d never gotten fat, she thought, kissing his throat, I wouldn’t even have them.

Someone touched her leg and she was watching Aimee Mann sing “Stupid Thing” on Late Night, her hand down the front of her striped pajamas, while her friends dozed all around her in the living room. A voice murmured not far from her ear and she was listening to the slap of flesh on flesh as her parents made love in the next room over, her mother crying, “Oh, Stan, put a baby in me. Please, Stan. God. God!”

Someone peeled off her underwear, working them over her thighs and out from under her weight. She was on her back now, shredding tulle and taffeta with hands and scissors, the sink and the tile floor all covered in locks of her long, dark hair. Their memories flowed through her like tributaries into a river, the rush of smells and fractured images growing louder with each passing moment. A dog lying broken on hot pavement. Wind turning the green and silver leaves of a great willow. Something dark and spicy simmering in a pot on the stove, the smell of it blooming out in a translucent cloud as her mother helped her lift the lid. A little hand gripping the edge of a doorframe and phlox nodding in the sunlight and the feeling of dark mud, fine sand, red clay between her toes and here and there the visions overlapping, spliced together awkwardly so that the images formed ghosts of one another twisting in the particolored daydream haze. Exhaling weed smoke as the world dilated around her. Stealing into a laundry room to paw through leggings, skirts, and panties, to let another boy dress her as though the pilfered scraps were finery and she was Marie Antoinette. She was Nadine, stepping from the fire into her open arms.

Tawny hair spilling soft over Shelby’s shoulders. It felt like Nadine was with them, or she was, or would be again someday. Shelby kissed her. She pulled the other girl’s grinning face up to her own and made a seal between their mouths, sucking and licking hungrily as hot tears ran down her cheeks to salt her lips. There was a finger in her, spit-slick and tentative, and someone was licking her hip where it met the curve of her belly, and someone was kissing her, someone’s mouth was at her little breast, someone’s hand held her jaw gently cupped. There were hands that feared her, hands that held desire and disgust in equal measure, hands that wanted her with a deep, burning heat, and all of the hands were Nadine’s and none of them ever would be again. She had never come with someone else before, but she came then, not once but twice, first in an emptying rush that left her gasping at the center of their human knot, fireworks in her ears, and then in a long, slow shudder which seemed to cover all the world’s sounds in a thick drapery of silk.

Shelby fell asleep still tangled with the others, still seeing what they saw, and dreamed of swimming somewhere warm and blue and trackless. In the morning they lay for a while in the pale light of dawn. It felt strangely grown-up, that hour in that empty place, chatting in hushed voices as one by one they rose and drank and started to prepare to leave. It felt to Shelby as though she were peering into her own future, into a world of bills and paperwork and answering phones with a big fake smile in her voice in which nonetheless there would be moments like this, moments of clarity and love when everyone around her would understand the things she’d been through in her life, when they could be together in the arms of something greater than themselves. In the bathroom, the dead man’s skeleton curled in the shower, she cried for Nadine until no more tears would come.

They left the bunker not long after.

XV THE DESERT

Jo led the way down through the foothills, following the path of a dry stream. The others walked strung out behind her, no one talking about what had happened last night in the bunker’s soft, enfolding dark, that pale stripe of moonlight falling across their backs and limbs and open mouths. Her legs and pelvis still thrummed with the power of it, like static building in her veins, but it no longer felt completely real. Shame and exhaustion crept back in the farther they walked and the more the world became about wet socks and blisters and the crackle of dry air in thirsty throats. Felix’s best guess was that they had a two-day walk ahead of them, maybe more.

They had just passed beyond the forest’s edge and out into the flat country when the noises began. Jo turned at the first distant blast of wood exploding under pressure. The treetops swayed far back along the slope. That’s close to the bunker, she thought, her heart hammering. She still had the shotgun, for all the good it would do. Wood splintered. Groaned. Cracked with gunshot reports as forty-foot ancients toppled to the forest floor some miles behind them, the thunderous boom of impact presaged by the rippling crackle and snap of branches breaking. They stood in silence as the giants fell.

The squeal and clatter of stone against stone soon joined the cacophony. Dust rose up from among the trees and plumed from rockslides which grew and spread, gouging vee-shaped wounds in the dead forest. A scream came from the midst of all of it, not the strangled choral wail that had risen from the burning house but a sound like dogs at hunt in an old movie, a layered baying interspersed with a shrill screech of rage. It echoed in the hot, dead air until another cry, smaller and more distant, came up from the fading sound to meet it.

“We need to go,” said Jo, finding her tongue.