“Easy,” the pastor rumbled. His voice made John think of a Morlock, hulking and filthy and secretive, toiling under the earth. His mother had read him The Time Machine when he was seven. He’d had nightmares about things coming up out of hatches in the ground for weeks. “It’s just a little blood, sissy Mary.”

Not since what happened at the lake.

The thought came from nowhere. He’d been noticing things like that more and more. He didn’t have any memories about a lake. Nothing worth calling up, anyway. For an instant, as he looked away from the needle, he saw Gabe lying curled on the floor under the cabinets, but it was just his eyes playing tricks on him. Gabe was gone. Jo. Brady. Quiet little Smith, who he’d never really gotten to know. Everything was moving so fast. Stinging pain as Mrs. Glover drew the syringe from his arm. A little way off Nadine stood with her back to the oven, still pale but no longer bleeding. She wouldn’t meet his eye.

“All right, big boy,” said the pastor, heaving John to his feet. Blood trickled from the pinprick wound in his forearm. “Next.”

The Cheryl-thing took an ampule from each one of them, working quickly and efficiently. When all five glass vials lay side by side in a little tin tray left out on the polished kitchen table, she took them all and left the kitchen. Pastor Eddie left a moment later, bending down to kiss his wife on his way to the back door. Their tongues flicked between their mouths. A wet sound. She looked so tiny next to him. John felt a momentary flash of embarrassment at the thought of what he and Malcolm must have looked like to the rest of the camp last night.

I am never going home again.

Mrs. Glover broke a match from a book left out by the salt and pepper shakers, struck it, and lit a cigarette. He’d never seen her smoke before that day. The others sat and stood around the kitchen. John joined Felix by the cabinets under the sink, lowering himself to the floor and letting out a long, slow breath. His whole body wanted to run, his heart pounding, his head still aching, but there was nowhere to go. Nothing to do. Men at the doors and Mrs. Glover sitting there and smoking, like nothing was wrong in the world.

“What are you going to do to us?” asked Felix.

Mrs. Glover took a long drag off her cigarette. Ash crumbled from the tip and she waved it away before it could settle on her skirt. “When my daughter was three,” she said, blowing swirling trails of smoke from her nostrils, “she was diagnosed with leukemia.” She took another drag from her cigarette, the cherry flaring orange and red. “Our church prayed. Our neighbors. Our families. We took her to tent revivals. Homeopaths. To Sloan Kettering and St. Jude’s. Dieticians, hypnotists. I even took her to a shaman, near the end. He covered her in grease and gabbled over her, filled the tent with steam and smoke, poured cold water over hot stones.”

She pursed her lips and exhaled a long plume. “I was so desperate. Janey was just skin and bones by then.” One of her hands flew to her right collarbone, fingers stroking its prominent ridge without apparent thought. “You’d touch her arm, just while you were talking to her, and leave these big ugly bruises like you’d beaten her with a mixing spoon. I would have done anything. Believed anything. One night when I brought her home from a week of observation, when I carried her into the house in my arms like she was nothing and tucked her into bed, there was a message on my answering machine. Thelma Nielson, a woman I knew from church, telling me she’d heard from my mother-in-law’s friend Sookie Carmichael that the week before she—Eddie’s mother, Nora—had bailed him out of jail in Ranahoe County, and the word was he’d been caught blowing some seventeen-year-old boy whore with a purple mohawk, and did I need anything? Was I all right? Oh she hoped she hadn’t upset me.” A bitter smile. “Purple. I think she made the color up, to make it more delicious. To have a little extra texture to savor while she chewed on what was left of my life.

“He came home later that night. We didn’t talk about it, but he knew that I knew. It was like that for months. He slept in his study. He hadn’t touched me in years anyway. So we kept it up until Janey died, that May. It was nineteen eighty-one. After the funeral, the first moment Eddie and I were alone in the house, we had a fight. It was like everything we’d held inside ourselves came pouring out at once, more and more of it. Black bile. Ugly things. He begged me to stay, to stand by him in his struggle. He promised he’d get better, but all I could think was that he was going to use my daughter’s ghost to guilt me into giving him a fig leaf while he carried on with his boys.

“In the end I walked right out of the house and into the desert. To die, I think. Eddie’s problem. Losing Janey.” Her face twitched. “That was part of it, of course. The way her little hand uncurled from mine. But to tell you the truth, what sent me out the door that night, what made me turn my back on Eddie while he pleaded with me, begged, sobbed, was imagining the way the congregation would look at me from then on, now that Janey was gone and there was nothing to keep them from digging their claws into us, the way they’d tilt their heads, speak softly, gently, like I was the one who was dying, like their feeling sorry for me…” She pursed her lips, expression sour. “… that it mattered. I couldn’t face the thought of that much pity.

“So I walked. I walked until the sun came up. I was thirstier than I’d ever been before, and so weak I could hardly stand, but I did, and I kept going until it was dark again. I don’t know how long I was out there. Two days? Three? But I remember the stars.” Another exhale, smoke coiling around her skeletal wrist as she drew an arc in the air with the cigarette’s burning tip. “The Milky Way … and I remember drinking water near the mountains. It made me sick. Shitting my guts out. Delirious. That was when it found me. It brought me here, to its crater, and showed me what it could do.

“A few days later I went home, and it came with me. It fixed Eddie. Now it’s going to fix you, too.”

Shelby was crying. Nadine had her arms around the shorter girl. John put his head in his hands. He felt sorry for her, for this starved and deranged woman holding their lives in the palm of her hand, for her long, lonely, frustrating marriage. And then he thought about what Gabe had said about Candace, about how she’d been replaced, which led him to the memory of Pastor Eddie’s parting kiss just minutes before. What kissed her? The thought chased itself around his mind until it felt like he would never think of anything else. What puts its mouth on her mouth? What did Jo hear her having sex with? What touches her at night? Does she want it? To let it touch her?

“You’re insane,” said Felix.

Mrs. Glover smiled slightly. “Maybe,” she said. “But soon you’ll be dead, and I’ll have my daughter back. It’s been growing her for me. So what does the rest of it matter?”

Cheryl appeared in the doorway to the back hall, sliding easily past Dave. “They’re clean,” said the counselor. “It’s ready.”

“All right.” Mrs. Glover stubbed her cigarette out in a porcelain ashtray. “Take them down.”

In the laundry room a door stood open to the left of the machines. The air smelled of bleach and warm cotton and Nadine clung hard to Shelby’s hand with her uninjured one, hoping no one in the kitchen had noticed her turning on the gas and palming the plastic knobs. They were in her pockets now. Probably someone would smell it and turn it off. Probably they’d all be dead long before anything happened with it at all. It still felt better, knowing she’d thrown one last punch.

Marianne took hold of a bar that must have been concealed behind shelving during laundry shifts and hauled back on it. A secret door, set flush with the wall, rolled smoothly out of the way. Behind it was another, plain wood with a tarnished knob. Smiling broadly, Corey opened it. Thick, humid air stinking of corn syrup and cat shit rolled out over them. “Oh my God,” breathed Malcolm, hands over his mouth and nose. “Oh Jesus fuck-me-running Christ.”

Behind the door, a set of concrete steps led down twenty or thirty feet to a bare dirt floor, and a short way from the foot of the stair, Gabe lay curled on his side next to another boy with whom something was terribly, monstrously wrong. It was Gabe’s size and shape, just about, but its face was split from chin to forehead just like Corey’s had been, and from the slack-lipped gap spilled a thick mass of tendrils that stirred weakly in the muck surrounding the thing. Behind it lay some sort of hairy, membranous egg sac, now deflated. Nadine stared. Even after what had happened in the barn and then in the cabin, even with the stump of her missing fingers burning and throbbing through the handkerchief Shelby had knotted over and around it, the stench and the cavern and the thing lying down there next to Gabe in the fluorescent glare all made her feel like she was losing her mind. It couldn’t be real. It couldn’t be happening.

“Bye, princess,” said Marianne, smiling broadly at Nadine.

“Suck my dick,” Nadine snapped without thinking. Someone hit her from behind with the stock of a shotgun, knocking her forward a few steps. The doorframe caught her chin, reopening her split lip, and she spat blood as Shelby grabbed her arm and pulled her back from the stair. A few of the ranch hands laughed and it occurred to Nadine with a sick thrill of curiosity that some of them might still be human.

“It’s okay,” said Shelby. Her voice trembled, but it held. “I’m with you.”

The ranch hands and counselors herded them through the door and onto the narrow steps. Nadine felt like a steer in a run, the air thick with panic, something ahead beyond her comprehension except that she was frightened of it. Those air-powered bolt guns punching their little metal rods through the beef’s skulls. Two thousand pounds of meat coming down like a curtain. Marianne slammed the inner door behind them. The lock clicked. Below, the thing lying beside Gabe let out a low, sleepy burble like a baby talking in its sleep.

“I’m getting him away from that thing,” said Nadine, and as the words left her lips the horror of the reeking chamber seemed a little more bearable, a little more real. She went down the steps and crossed the broad expanse of dirt. The subbasement was huge, poured concrete walls rising fifteen or twenty feet to an arched ceiling supported by graying, splintery timber joisted with rusted plates and struts. A tunnel yawned on the far side of the room and the smell was even stronger in its draft than at the top of the steps, flyblown garbage and orange soda drying into sticky chemical waste on car upholstery. Nadine put her face in the crook of her arm and made her way to where Gabe lay on his side, pale and motionless except for the flutter of his pulse in his slender throat.

She knelt, fighting the urge to gag at the sight of the thing lying next to Gabe. Its eyes were closed, the uneven halves of its face slack and dead-looking. It had four fingers on its right hand, its fifth no more than a tender half-inch nub of raw pink flesh emerging from what looked like a burst blister. It was a little more solid than Gabe, too, its shoulders broader, its muscles more defined except where they drooped like sleeping snakes from the curved bones of its malformed legs.

“Is this the thing?” Shelby whispered from a short way behind Nadine. The others stood gathered there, not daring to come closer. “You know, from our dreams? The thing that replaced Candace. Whatever you want to call it. Some kind of monster, or a—” She gestured with both hands as though grasping for something.

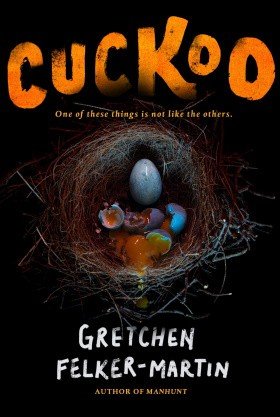

“Cuckoo,” John finished, and it sounded right. It sounded familiar. “No, I don’t think so. Or, not all of it. That thing it came out of looks like an egg; something must have laid it.”

Nadine turned her attention from that appalling thought to Gabe, slipping her arms under his and standing with some difficulty. He didn’t weigh much, but he was tall and bony and awkward to move. The thing’s tentacles slid from his face. It let out a piteous squeal, but didn’t follow. She had him halfway to the steps by the time he started to stir, snorting and retching in her arms. “Easy,” she said, trying to avoid his flailing hands. “It’s me! It’s Nadine. Just—”

That was when she heard it. People. It sounded like dozens of them at least, shuffling and wheezing and blowing, coughing and snorting and clearing their throats. It came from the mouth of the tunnel. A phlegmy, sputtering onslaught of respiration echoed and re-echoed from the tunnel walls, and the sound of something heavy dragging over rock and earth. A fresh wave of stench washed over her. As she backed gagging and coughing toward the steps, a dark mass appeared in the deeper gloom.

It squirmed through the archway, a tide of skin and greasy hair and raw, wet flesh pulled along by scrabbling limbs and bands of muscle cradled in buttery soft fat like the segmented body of some obscene grub. It was enormous, as big as an elephant. Bigger. Feathery limbs dripping with a cloudy, viscous fluid unfurled from its sides. The front of its rolling mass heaved and stretched, rings of doughy flesh forming and inverting as new limbs squirmed their way out of its bulk. It clawed at itself with soft, unformed fingernails, peeling away mats of sodden hair and flaking, scabby dermis. Dirty feathers covered its back like an eagle’s ruff. Nadine couldn’t seem to find her breath.

This isn’t happening.

A particularly large crust of dead flesh tore loose and from the quivering vaginal wound beneath it came a face, wriggling its way slowly out into the open air. A girl of three or four, wisps of dark hair plastered to her scalp by that same nameless slime, eyes rolling from rheumy white sclera to huge black pupils. The pupils shrank. Muddy irises bloomed from them. The face began to age. Its skin grew tight, dried into brittle flakes, and tore, the pouty mouth cropping at loose scales of the dandruff-like refuse. Bones lengthening. Nose growing, baby fat melting away. Vestigial features formed and burst like boils in the sagging flesh of its neck. Another layer desiccated into eczema and ripped with a dry, satisfying tearing sound. It was almost to the other Gabe now as it picked away the dead mask, fresh clumps of black hair spilling from its scalp where its skin sloughed free. A woman, wrinkles at the corners of her eyes, brow furrowed in concentration. Its mouth worked, lips fluttering in separate segments before knitting together and pulling tight over crooked teeth.

“Up,” it hissed, humping itself up on its own bulk, sluglike pseudopods of fat and muscle dewing from its belly to support it. “Up.” It hit the sleeping figure with one of its knobby, sticklike fists. The thing opened its eyes. Gabe’s eyes, round and baby blue but lifeless as the marbles in a doll’s porcelain sockets. Whatever it was, however it saw the world around it, those eyes were just for show, no different from the way some bugs looked like leaves or bark, or predators. Camouflage.

Nadine stared, a picture beginning to form in her mind. A thing with her face getting on a bus back to Kansas, riding in silence until it came at last to her family’s home, to the red front door and the old granite hitching post, and went into her mother’s arms. What would it do with her face? Her life? She felt violated. She felt as though insects were crawling under her skin.

The creature looked at her and a smile split its face, a smile so wide its features began sliding back over the soft contours of its skull until all that remained was skin pulled so tight that it was shiny and translucent, and nightmarish rows of teeth nested in infected tissue. Then it spoke, and its voice left a white-hot hole in her mind like a cigarette burn on tender skin. She was on her knees. She was screaming as blood poured from her nostrils.

I will tell you what becomes of the flesh, Nadine. Lovely Nadine with your long, long legs and your hair like summer. Your father thinks of you as he touches himself. He dreams of your wet little holes, your long, graceful toes. You suspect these things. You understand them, but there is nothing you can do. This is the nature of separation. Pain. Loneliness. Deformations of desire, all to bridge a gap that cannot be bridged, save through union with us. With me. Aren’t you tired of being afraid, Nadine? Of being lonely? Tess will never understand you. Nor will this sad littlething, trying so pitifully to reshape itself with neither art nor understanding.

She was vomiting. She couldn’t see out of her left eye. Hands had her. Took Gabe, who was waking now, crying out and coughing up something thick and black and sticky. She was alone. She was alone and her brain was on fire and there was nothing, nothing but an endless darkness clawing at her stomach, eating away at her insides.