The thing crawled toward him. The wooden bird emerging from the beautiful Swiss clock in his grandmother’s living room, its little wings flapping stiffly, its neck thrusting out as it cried, and his headache roared back, piercing him through the skull between his eyes, and he saw:

A slab of meat and rough, dense bone plummeting through the atmosphere. Below, the jagged lines of mountain ranges crawling between lakes and deserts. Crosshatched farmland alternating brown and green. The glint of water. Closer. Great scar bisecting old, dead soil. Clumps of concrete growing tight and high like fungal stalks. The sea stretching away over the curve of the horizon. The lifeless plain rushing toward it, and then impact, body blown apart like a water balloon bowled through glass and nails, flesh strewn throughout the crater clawing back toward itself, brain waking by slow, sticky degrees as neurons knit and memories propagated through uncomprehending meat. Huddling in the shadow of a rock escarpment as the sun boiled its way across the sky, lung networks like bunches of grapes struggling to process the thin air as it fights to grow new alveoli better suited to its new conditions.

Minutes pass. Hours. The last straggling gobbets of its biomass join it in the thin band of shadow. Some it allows to fuse with its wheezing bulk. Others it crushes and discards, smelling cancer on their burnt and flaking skin. This place is killing it. Flesh sloughs from its bones in scabby, lifeless sheets. Not the paradise it seeks but an irradiated wasteland where poison rained down on its sensitive skin. It is dying. Every breath is hard-fought. It snorts thick yellow mucus from its half-formed mouths and oozing gills. Lesions bloom where its slack folds rub up against each other, auto-frottage lubricated with its watery, discolored blood. At last the sun sets. It shivers in the dark, temperature plummeting, and leaves a hunk of itself the size of a stray dog twitching and vomiting behind it as it presses closer to the stone outcropping, still warm from the sun’s touch. Its thoughts race. Nothing living here. Nothing to take into itself and turn to its own purposes, to use as a fleshly lens through which to understand this barren place.

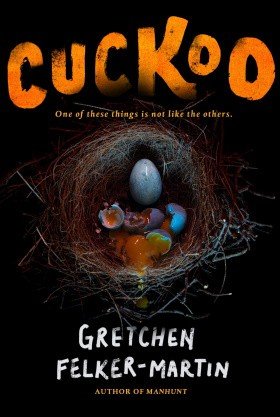

Nothing, until in the silence of the deepening night it hears a plaintive chorus rising from somewhere above. A bright, vulnerable cry. Its milky, watering eyes blink. It turns toward the rock face, struts of cartilage unfolding to support new tissue as its ears expand, and with palsied, trembling claws it finds a crevice in the stone and starts to climb. It secretes adhesives through the pads of its limbs, sprouts fat, muscular tentacles lined with suckers, and inch by torturous inch, even as its vision blurs and its blood—starved of the strange compounds of its native atmosphere—hammers through stiffening veins, it climbs toward that shrill, innocent sound. Little pink things hidden in a recess in the rock, beaks open in needy supplication, bodies so delicate it can see their frantic heartbeats through their skin. Blind and helpless, vestigial wings folded tight against their sides. It reaches out and they stretch up toward its twitching digits, begging, it thinks, to be fed.

Four of the five it eats, plucking them from the nest of brittle twigs and dusty, matted fibers and dropping them still crying out into a prehensile mouth. Bones as delicate as matchwood snap between its jaws and in the meat, the marvelous meat, so perfectly suited to this world of horrors, is the blueprint for the lungs it needs, a map of flesh, muscle, and organ tissue evolved to endure this world’s leaden gravity, its caustic atmosphere and poison sun. Eyes that drink in the full spectrum of wild colors, nostrils lined with minute, sensitive hairs which capture particles of complex stink, and still the fifth thing cheeps at it, beak gaping. Waiting, it realizes, for its progenitors, the hosts from which its graft was cut. They will come and feed it. How perverse, to care for one’s own leavings. Useful, though. It eats the last survivor.

It sheds a little lump of tissue in the nest, now empty as that gaping beak, and along the sympathetic link still binding them together it begins to whisper of another form. A feeble thing, its adult shape still months away, a hazy smear of genetic destiny extrapolated from the bulbous head, the blind eyes and tiny claws as delicate as glass. Even if it dies out here, even if its flesh fails and its long voyage is all for nothing, seeds of the meat will be sown, and as the crude little double begins to cry out to be fed and its true parent scurries down the sheer rock face, the harried egg-layer flutters back to light on the nest’s rim and twitter in fear and confusion at her missing offspring before opening her beak to vomit in the upturned beak of her sole remaining nestling.

Her child, and its.

Jo stayed in the tree until dawn, dropping once or twice into gray dreams of pus and sores and clutching hands from which she woke in a cold sweat, ears perked for the sound of footsteps or the roar of engines. The chill seeped into her a little more each time she stirred. Her fingers ached. Her face itched where the wind had burned her. Once she dreamed she was lying on her back at the bottom of a tiled shower, cold water dripping on legs she couldn’t move, a stomach she couldn’t feel. She woke to find she’d peed herself. As the first needles of gray light pierced the thickening clouds she shinned down the pine’s trunk and wiped her sap-smeared hands on the seat of her jeans. There was no sign of Brady. No blood. No claw marks in the dry, colorless earth. She pressed her fist to her mouth to stifle a sob.

Part of her wanted to lie down in the dirt and scream until somebody found her, scream and scream until whatever the fuck was happening out here at the ass-end of the world wrapped itself around her and dragged her under. Living meant making sense of what she’d seen last night. It meant making a place in her conception of reality for the thing Mrs. Glover had led into the basement, for the thing wearing Cheryl’s face in the darkness under the trees.

They aren’t just going to kill us, she realized. They’re going to take us. Our faces. Our lives. Oh, God, please don’t let them get me. Please.

That was when she heard the dogs.

XIII BROOD PARASITES

Shelby heard the cabin’s steps creak underfoot and knew the dream was over. No time to get out through the trapdoor. No time to hide under the bed or in the tiny bathroom. She didn’t open her eyes. It would only make it worse, the moment they took her from Nadine’s arms, from the peace of the other girl’s sweat and sawdust smell and the thrill of being skin to skin with her, still tingling and tired. This must be why they call it making love, thought Shelby.

She was crying when Corey and Marianne came in and dragged her from the bed, crying when Nadine kicked free of the tangled sheets and threw herself on Corey’s back, biting and clawing, raking his eyes with her nails.

When Corey’s face broke open like a spider’s legs unfolding, though, and the puckered mouth within snapped shut on Nadine’s first two fingers, then Shelby began to scream.

The counselors zip-tied their arms behind their backs and marched them up a plywood ramp into the bed of one of the pickups, where Malcolm, John, and Felix were already sitting. They brought Shelby and Nadine up last, Shelby with duct tape over her mouth, Nadine bleeding freely where two of her fingers just … ended, as though someone had snipped them off with a pair of gardening shears. There was no sign of Gabe, or Jo, or Brady, just the five of them herded up over the tailgate.

“You think they’re taking us to Disney World?” Malcolm asked, wishing he could scratch his nose. “It’s peak season, so we’re just gonna be waiting in lines all day.”

“Malcolm,” said John. “Could you please shut up?”

Malcolm swallowed past the lump in his throat. He couldn’t stop looking at Nadine’s hand. He’d thought she was so cool, so tough, so grown-up. How had he missed that she was just a fucking kid? They were all just fucking kids. “Copy that, chief.”

The truck’s engine turned over. It pulled away toward where two ranch hands stood by the open chain-link gate. Through the dirty glass of the cab’s rear-facing window Malcolm watched Corey wipe blood from his chin with a handkerchief. The counselor’s face was covered in angry red scratch marks.

Felix kicked the tailgate hard enough to rattle it. “Fuck,” he snarled. He kicked it again. “Fuck.” Again. “Fuck!”

“Take it easy,” said John.

“FUCK!” Felix screamed, rolling onto his side as he doubled up his legs and kicked again, jolting the tailgate hard against its locks. He was crying. “FUCK! FUCK, FUCK!”

Malcolm wished he’d stop. He still felt so weird after whatever had happened the night before. As he met John’s gaze across the bed of the truck, he remembered their mouths sealed together, their tongues thrashing, and the painful stiffness in his briefs. His thighs were still sticky from it. He’d thought it would be too much, John on top of him, but it had been … nice. Soft, like drowning in molten marshmallow. In the light of day he felt embarrassed by how eager he’d been. How much he’d liked it.

Something must have shown on his face, because John turned away from him and set his jaw as though determined not to cry. You’re the Tom Cruise of fucking up, thought Malcolm. You’re the fuckin’ Kyle MacLachlan of pulling a boner. Whatever. He’s better off without you.

“They’re not human,” said Nadine. Her face was ashen, her voice hardly audible over the rattling roar of the truck’s progress. Still, they all heard her. Malcolm watched her blood slosh back and forth in one of the truck bed’s plastic channels.

“They’re monsters, and they’re going to kill us.”

John rose awkwardly up onto his knees as the truck started its descent into a tiered depression in the shadow of a wind-smoothed wall of rock. He couldn’t stop staring, could hardly hear Felix and Malcolm telling him to sit down before he fell out of the bed. Trees. Grass, which he knew from the summers his father had made him work at Shearwater Meadow, the golf course on the edge of town, drank water like a fish. And there was water to be had, entire pools and rivulets of it splashing down the tiers in miniature waterfalls through stands of bamboo and sumac, past overgrown flower and herb gardens. Scintillating blurs flitted here and there among the nodding blossoms. Hummingbirds, in the middle of the desert.

“Oh my God,” he heard himself say. The look of ashamed anger Malcolm had given him earlier seemed all at once a tiny little thing, inconsequential against what he was seeing. Even if they were about to die, even if the camp’s staff really were monsters, this was the most beautiful thing he’d ever seen in his life, an awe-inspiring waste of resources on a scale he couldn’t begin to imagine. “This is impossible.”

“Well it’s doing an amazing impression of being possible then,” Malcolm snapped. He was sulking. Probably embarrassed about how he’d begged John to climb on top of him and grind, how he’d come right away and broken down crying, mumbling nonsense as he fell deeper into whatever trip they’d been sent on. Doors and phlox and Mary’s hand and Mommy, Mommy, please don’t do it. John had felt so tender toward him then. He’d held the skinny boy, Malcolm’s chin on his shoulder, and stroked his hair as he cried until it passed and they went back to kissing, to whispering sweet things and touching, still afraid but eager. Hungry. It was over now. It had crumbled at the first touch of sunlight.

John sank back down into the bed, trying to ease his legs out from under him. He nearly tipped over onto Felix, who’d been lying silent and unresponsive since his outburst when they were loaded aboard. “Sorry,” he said. The truck hit a bump in the narrow dirt track and a flock of game birds exploded from the undergrowth to the side of the road, wings whirring loudly enough to drown out the noise of the motor for a fleeting moment. One came close enough for him to see the raw, sticky flesh of its underbelly, as though it had torn itself loose from something greater and gone winging off in terror on its own. Rags of skin trailed after it, and then the birds were gone into the bamboo, crashing through the pale green stalks.

In the yard outside the farmhouse they climbed down out of the truck with Garth’s help while a few ranch hands kept watch at a distance, shotguns shouldered. Mrs. Glover stood smoking on the porch, a fringed shawl wrapped around her bony shoulders. She reminded John of his stepmother, all protruding ridges and hard angles, her skeleton resentful of the skin encumbering it. Her stare gave him the bizarre urge to wrap his arms around his belly, to hide it from her, to protect it from her fleshless fingers. She looked at him like he was something dirty.

“Where are you taking us?” shouted Felix. He was crying again, the most emotion John had ever seen from him. “Where’s Gabe? Where are Jo and Brady? Fucking answer me!”

Garth slapped him hard across the face. Felix went over, unable to break his fall with his bound hands, and Garth kicked him in the stomach hard enough that he folded in on himself with a harsh, coughing sob. “Stop it,” Shelby moaned through her duct-tape gag. “Stop it, stop it, stop it.”

Garth seized Felix by the back of his shirt and dragged him the rest of the way to the porch as Corey and the other ranch hands closed in to force the rest of them toward the house. John brought up the rear. The guns were making him nervous. He’d never liked them, had turned white on the spot when his father gave him a rifle for his thirteenth birthday. It made his heart rabbit and his mouth turn dry when the sun glanced off those oiled barrels. If we run, they’ll shoot us.

On some level, he thought as he climbed the porch steps, he’d really believed Nadine’s plan would save them, that they’d swipe protein bars from the kitchen like Tom Sawyer packing his bindle and then traipse right out of camp and have a real adventure, that Jo’s grandfather would pick them up in a big gold Cadillac and take them all for hamburgers and milkshakes. He’d never thought it would wind up here, kids held at gunpoint by grown-ups, a toe on the last line of the unspoken pact between their worlds: If you obey me without question, I won’t kill you.

“It’ll all be over soon, babies,” said Mrs. Glover as they passed her by. Her bony fingers brushed John’s face with something between lust and loathing, the expression etched deep enough into her skull-like mask of a face that he stumbled back a step and nearly bowled Shelby over. Corey shoved him back in line. They went into the house, and as John stepped over the threshold a white-hot needle of pain zapped between his right eye and the back of his head. He bumped against a side table. Something shattered on the floor. Porcelain.

If the moon is waxing gibbous and the limpid limpets shimmer, who is watching from its zenith as the bursar carves his dinner?

John remembered something as he fell to his knees and vomited, heaving bile and mucus up on the clean carpet. Something Gabe had said that night they’d all sat around drinking and talking about their dreams. About the holes they dug when they closed their eyes, and the things they found in them. His own face smirking up at him from beneath clods of runny, sucking mud. His own fingers curling around his wrist as he knelt to dig deeper. Someone’s beaming shit into our heads like Professor X? I mean, come on.

The next thing he knew, he was sitting in a chair in a big, well-lit kitchen with one of Pastor Eddie’s dinner-plate hands gripping his shoulder like a vise as the Cheryl-thing drew his blood. The syringe filled quickly, sucking at his forearm like a huge mosquito made of glass and metal. Someone had cut his zip tie. John let out an involuntary whimper and tried to jerk back, but the pastor’s grip restrained him. The others stood all around and Dave and Corey barred the doors, incongruous in stocking feet. They must have left their boots by the doormat.