“We have to go,” said Jo.

They ran.

XII AND YOUR ASS WILL FOLLOW

They were halfway to the crater’s lip when they heard it: a high, horrible gobbling that rose up and up until it seemed to fill the air, to come from all directions at once. Jo could hardly think. She stumbled and staggered, her balance suddenly thrown off as an awful pressure built in her ears. Just when she thought her eardrums would explode, pain knifing hot and dirty deep into her skull, the shrieking ceased. She grabbed Brady’s hand and dragged him onward. They crashed through a copse of magnolia saplings, knocking one of the slender trees askew from its braces in a shower of fleshy white petals. Her headache was getting worse, the white spot growing in size and a point of pitch-darkness now visible at its center, like the pupil of an eye.

Up to the next tier, panting for breath as the sounds of pursuit grew louder. The flat crack of a rifle shot. A clod of earth and grass leapt from the slope a little way ahead of them and then a woman’s furious yelling, incomprehensible at a distance. No more shots came. They struggled onward in the dark. Behind them, the distant sounds of bodies breaking trail through vegetation. This place is impossible, thought Jo. How did I ever fucking believe this could be real? All this water …

“Where?” Brady gasped. His face was brick red, his legs trembling. They weren’t dressed for the cold.

“Trees,” Jo wheezed back. Her thighs were burning. She felt a ridiculous rush of gratitude toward Cheryl’s brutal morning runs, which had, if nothing else, left her with legs that could stand toiling uphill with Brady hanging on her arm. She looked and saw his lips were moving. He was saying something, and with a galvanizing thrill of horror she realized that she could hear the same words his mouth formed.

I love to love ya, Joey baby.

She moaned in horror, despair bubbling in her guts as she thought again of breathing the world in, of inhaling reality so that it covered her insides and erased the barriers of skin and thought. What’s happening to me?

You’re digging up Roy, laughed the voice of her subconscious, Brady’s lips flapping in time with its wet, throaty gurgle. Let’s see if old Roy still has his claws! Let’s see if his teeth are still where we left ’em! You know a vulture’ll ride a carcass miles and miles downriver till the pressure from gasses building up inside ruptures the animal? That’ll be five seventy-eight, first window! Arentcha hungry, Joanna? Don’t you want some of that dee-licious Szechuan spicy chicken, or are you running for office?

Dead dog, guts spilling out of him, legs and neck twisted the wrong ways as he shivered in the driveway, piss and blood run down its slight slope. Eli. Roy. Names she didn’t know. Her father stepping from the car. A man she’d never seen, big and broad and pale with thinning golden hair. No, dark. Choking her on the living room floor because of what she’d done to the dress. She ran uphill through soiled gore, clawing at the loose black soil, which was dog flesh furred in blood-soaked gold. Then it was over, the white spot in her vision popping like a pimple as she dragged Brady up over the final ridge and onto level ground. She sobbed, but only once. There wasn’t time. Floodlights washed the crater in blinding light and stabbed at the dark above.

The white spot formed again, and this time she knew what it reminded her of, with its round form and its little glistening black head. A grub. A stupid little grub chewing at whatever was in front of it. Oji heard me right, she told herself, looking back down the tiered slope. Dark little figures coming toward them, but still far away. He heard me right and he’s going to figure out how to get here, and he’s going to save us.

She could just make out the brown smudge of the tree line at the nearest extent of the mountainous foothills, the dark outline of the peaks above just visible in the predawn sky. Pines dead and living, left withered by years of drought, marched over the rugged earth. “Come on,” she panted, forcing herself to break into a jog. “Come on, come on. We can make it. We can do it.”

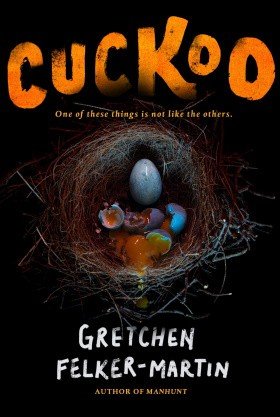

Cuckoo! shrieked the voice in her head. Cuckoo, cuckoo! Do you hear it, Joanna? You’re not going home! Someone else got your seat on the bus, and she’s just so excited to meet your parents, to meet that feeble old man rotting away where he’s no good to anybody and wring a little something useful out of him. You wouldn’t believe what you can do with just one tired old man, Joanna. With his skin and his fat and the soggy, failing neurons in his demented old head. You won’t recognize him when I’m done, but he’ll recognize you. He sure will. Cuckoo.

Cuckoo.

Somewhere behind them in the crater, an engine roared to life. Another followed it. Jo ran faster toward the dark under the trees, Brady at her side.

Gabe woke as Corey pulled him out of the bed of the truck. His feet slipped off the tailgate and hit cold gravel. Corey had him under the arms and he couldn’t seem to move, so he just hung there, heels dragging as the counselor hauled him onward. He was freezing and his thoughts felt like molasses. His breath came in puffs of mist. It was still dark out, but harsh floodlights bathed them. There was a house. A barn. A towering rock face. And around it all, impossibly, the garden the girls had told them about and which he realized he’d never quite believed existed.

Somewhere close by another truck peeled out, tires spitting grit and gravel, but Gabe couldn’t see it. His head didn’t want to turn when he told it to. He thought he might be drooling. He gave me something, he thought, and the grown-up phrase “slipped him a mickey” surfaced from somewhere in his subconscious like a shark’s fin cutting water. A dog lying dead on the ground. A hand emerging from the dark. He was so cold.

Corey dragged him up the steps of a wraparound covered porch, past Garth and another ranch hand, who were looking out into the floodlit gardens, guns raised and eyes narrowed, and in through the front door, which was braced open with a chipped red brick. His ankles thumped against the edge of each stair, but he hardly felt it. The carpet in the entry hall was stained. Mrs. Glover sat in one of the high-backed armchairs by the staircase, a cigarette in her hand, a linen nightgown cinched around her tiny waist. Family photos marched along the steps at their backs, older and older as they rose toward the second floor. She looked like a toy beside her husband. He noticed a little girl in Mrs. Glover’s arms in the first few, his mind snagging on the detail.

“Thank you, Corey,” she said in her hard little voice. Her jaundiced skin was stretched so tightly over the bones of her face that Gabe thought she looked more like a skeleton than a person. “Take him down to the basement.”

A door. A stair. A long, dark laundry room and at its end an open pantry. They passed by it all, Corey dumping Gabe against one of the dryers to free his hands for prying open a door concealed as part of the unfinished wall. A bloom of noxiously sweet air, fetid and hot, like a garbage can left out in the sun after a warm summer rain. He tried to move, but he could hardly curl his numb lips. He could feel drool soaking the collar of his T-shirt. He could feel cold cement under his backside.

Please, God, he prayed as he hadn’t since the fourth grade when Father Dolan told the congregation there was “nothing gay about Hell.” Please, don’t let them do to me what they did to Candace. Don’t let them do it, God. Please. I’m sorry. I’m sorry for everything, I didn’t mean it.

Corey heaved him up over one shoulder so that all he could see was the back of the counselor’s striped button-up and then they were going down again, each step a jolt through Gabe’s stomach. The shock of level ground. Dirt floor glimpsed between Corey’s boots and then the older man unlimbered him and dropped him without ceremony to the ground. Gabe sucked air, trying to fill his lungs as he stared up at the joists above, and then Corey set the toe of one boot against his cheek and tipped his face over to look to the right.

Once, when he was twelve, his class had taken a day trip to a local dairy farm. It was calving season and one of the cows was close to delivering, a sight some enthusiastic teacher had decided would do the school’s coddled best and brightest some good. Get some dirt under their nails, or at least show them what it looked like to achieve proximity between one’s fingernails and dirt. What that teacher hadn’t counted on was a word Gabe hadn’t known before that day. The word was “prolapse.”

The thing lying there on the warm dirt floor looked much as the cow’s uterus had oozing over the filthy straw, a great pool of bloody, hairy tissue inside which some fragile thing thrashed weakly, limbs like tent poles pushing at the near-translucent membrane. Except it was bigger. Much bigger. A shapeless, jiggling sac of flesh nearly six feet long and full of cloudy pinkish fluid, all covered by a dissolving layer of matted hair. It looked, he realized, like the strange owl pellets he’d found in the desert.

Gabe heard himself screaming, but it was as though he heard it from a great distance, an echo of the real thing that tore at his numbed and tingling throat. He didn’t hear Corey walking away, or the door at the top of the staircase closing, or even—if indeed it made any sound at all—the sound of the dark humanoid shape in that prolapsed mass of flesh as it turned toward him, flailing through the soupy liquid in which it was suspended.

They reached the edge of the forest just as the truck’s headlights came over the edge of the crater, swinging wildly through the dark and then stabbing out across the open ground. Jo chanced a look back and almost brained herself on the underside of a dead pine toppled against its nearest neighbor. She slid under it, twigs scraping her scalp, a huge swag of dusty cobweb clinging to her face and shoulder. The roar of the engines grew louder. She crashed through dry brush and dead branches, Brady flailing somewhere to her left.

They broke into a clearing. Headlights stabbed through the night around them. Jo clambered over fallen logs, dry-rotted wood giving way under her hands and knees. She cut her leg on something—she didn’t see what—and warm blood slicked her shin and stuck her sock to her sweaty ankle. Car doors slammed somewhere behind them. Voices rose over the crash and crackle of deadfall underfoot. The slope pitched sharply up and Jo threw herself at it, kicking little landslides loose as she seized hold of roots and fallen brush, half slithering and half dragging herself up the grade. Halfway to the slope’s crown she nearly tumbled into the darkness under the exposed roots of a gigantic pine. She made her decision without thinking, leaping up to catch one of the huge, stripped limbs. It creaked under her weight, dead wood cracking, and she scrambled up into a crotch set just above it, wedging herself into an awkward position to push with hands and feet as pine needles and loose scales of bark rained down on her. She was twenty feet up at her best guess before she thought to look for Brady.

He was sprawled in the dirt at the base of the slope. He must have twisted his ankle in a hole or under a root, because he couldn’t get his feet under him. He clawed at the ground, sobbing in panicked frustration but still somehow with the presence of mind not to give her away by calling for help. I have to help him, thought Jo, but her hands refused to release their death grip on the old pine’s trunk and the ground seemed so far away, so unrelated to her. When the first flashlight beam slashed through the dark off somewhere to the right she realized then she wasn’t going to go back for him, that however brave Oji had told her she was, this was beyond the limit of that bravery. She was afraid down to the marrow of her bones.

Something came out of the dark just as Brady finally yanked his foot out of whatever root it had gotten stuck under. The thing had Cheryl’s face, but her skin sagged, hanging in flabby folds from her arms and drooping under her eyes so that red, glistening tissue showed in little crescents under them. Raw sores gaped at her hairline and on her bare arms among constellations of boils and blisters. She tossed her flashlight aside, scuttled up to Brady on all fours, and planted a hand between his shoulder blades, flattening him against the ground. He screamed as she bent to sniff the back of his head, a low, despairing cry of horror that made Jo want to double over and vomit. If I was brave, she thought, if I was really brave, I’d jump down now and help him fight her off. Maybe together we could take her, whatever she is. Maybe—

The Cheryl-thing bent her head to Brady’s neck. There was a wet, heavy slurping sound and Brady fell still, his cry cut off. When she drew back there was an oozing wound at the base of his skull, as though someone had slipped a scalpel in between his vertebrae. The thing threw back her head and let out a hideous shriek, that same high, frantic gobbling they’d run from in the crater. Jo nearly lost her balance.

They’re going to kill him. They’re going to kill him. Do something. Do it now. Now. NOW.

Pastor Eddie stepped into the moonlight at the clearing’s edge, the beam of his flashlight playing over the ground and the Cheryl-thing where it crouched atop Brady’s back. “Go and get the rest of his cabin. The girls from Four, too.” He looked at someone Jo couldn’t see. “It was that little nip with him, wasn’t it?”

“Yes, sir,” said a man. Garth, Jo thought.

Do it now. Do it.

“Cheryl, you’ll have to wake it up.” He bent and grabbed Brady around the middle, then straightened and slung the boy over his shoulder as though he weighed nothing at all. Brady’s neck flopped horribly. His limbs swung limp. Pastor Eddie blew out a frustrated breath. “Tell it we’ve got another runaway.”

Gabe stared at the wet, rippling surface of the birthing sac. Egg? Womb? Whatever it was. The thing inside thrashed pitifully, stub limbs churning murky fluid. Its lipless gash of a mouth stretched open wide. Wider. Jaw breaking apart, sticky strands of flesh stretching between the segments, pulling taut, and snapping as its forehead wriggled, furrowed, and split into three clawing digits. Within, dark eyes blinked furiously in no recognizable sequence as a loose wet slit contracted and fluttered its plump lips. A gap. A hole.

A single word slipped through the panicked morass of Gabe’s thoughts, the snatches of grade-school kisses and the taste of lipstick on his tongue, his mother’s hand, perfectly manicured, the news blaring from the old TV in the lake house living room as Tom Brokaw talked about the wall and the drone of a boat motor off in the distance like some ungodly huge fly, the scratch of nails on skin, and the word was: Cuckoo.

The thing spluttered out a cloud of silvery bubbles as its stump-ended limbs pressed at the surface of its sac. The translucent membrane bulged outward under pressure. Cilia like a jellyfish’s tentacles bloomed from the face, and from the cunt-like gash within a curved black stinger slid to neatly cut a slit in its cocoon. Its egg. Warm, sticky fluid splashed over the floor, soaking the back of Gabe’s shirt. The stinger withdrew. The tendrils flopped limp as the thing dragged itself out of the collapsing sac, dead tissue and sodden clots of hair clinging to its skin.

Don’t cry, beautiful boy, a voice hissed inside Gabe’s skull. You’re going home to mommy.