A closer look, however, reveals something quite different. First, it is noteworthy that the newsreel sequence purchases its praise of decentered and embodied forms of viewership with a curious denial of technological mediation. As the film entertains illusions of reciprocity between screen space and auditorium, it renders invisible—in accord with the formulas of classical Hollywood cinema—the materiality of representation and its codes of enunciation. When greeting Mac Allan, the film’s diegetic audience disavows the work of cinematic technology and mediation; it views films as self-contained realities. Believing that there is a real body out there present on the screen, Bernhardt’s spectators perceive images produced by modern machines as direct extensions of the body. Like ventriloquists, they render mediated effects as natural presences, and, in so doing, they fall prey to fantasies of reconciliation that deny class difference and unite engineer and worker, brain and hand, in consensual harmony.

Second, any reading of the newsreel sequence and its implied model of spectatorship will remain incomplete if it fails to address its counterpart at the end of the film, which depicts the climactic rendezvous between the American and European crews. In this sequence a long shot shows the

02-C2205 8/17/02 3:37 PM Page 58

58

/

Hollywood in Berlin, 1933 –1939

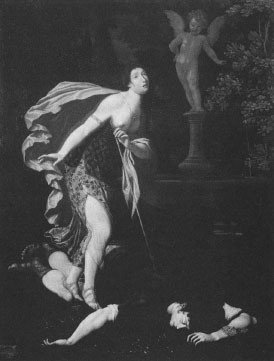

American workers gazing at the front wall of the tunnel, when—through a vaginal opening—a face suddenly appears, shouting “Hello, America!

Here is Europe!” (fig. 6). The tunnel’s wall here clearly resembles the screen in the earlier newsreel episode, and the image of male bodies confined to the dark tunnel refers back to the earlier depiction of cinema spectators. In addition, on a more formal level, the shot /reverse-shot pattern, the frontal long shot perspective, and, finally, the forms of address directly parallel the strategies used in the earlier sequence. Mise-en-scène and editing thus seem to substantiate what the viewer suspected all along: Bernhardt’s workers are moviegoers in disguise; his underground walls are emblems of projection screens, and vice versa; his film posits direct links between spectatorship and heroic work, between the mobilization of fantasy and the mobilization of the body for a higher cause. Yet what makes both sequences different is of course that, contrary to the ventriloquism of the newsreel interlude, the final breakthrough scene depicts proper bodies speaking with proper voices. Whereas in the earlier sequence speaking bodies emerged as silent cinema’s innermost fantasy, the climactic scene presents the attractions of sound film as the most viable tool to elicit awe amid industrial culture. Whereas Mac Allan’s silence in the newsreel sequence allowed the diegetic viewers to lend their own voice to the spectacle onscreen, in the film’s end the worker-spectators are struck with silence themselves. Cinema here assumes spectatorial silence as its new standard of respectability. It recenters pleasure and perception to incorporate earlier forms of spectatorship and publicity into a new hegemony.

Hegemony, Antonio Gramsci has argued, does not necessarily annihilate or fully replace undesirable ideological positions of the past or the present. Rather, it is characterized by the principle of articulation, that is, the effort to sift through competing ideological possibilities and experiences and integrate them into “the nucleus of a new ideological and theoretical complex.”19 Bernhardt’s film follows this logic of hegemonization.

Recapitulating the historical course from nonsynchronized to synchronized sound, from viewer involvement to spectatorial silence, from decentered to textually inscribed modes of spectatorship, The Tunnel absorbs different traditions and intends to transcend class affiliations and reach the widest audience possible. That this project of absorption reflects a political agenda can hardly be overlooked: the film articulates earlier forms of proletarian publicness to what it shows as the new hegemonic principle—masculine willpower and resolution, self-sacrificial labor, and submissive collectivity.

It is therefore by no means tenable to argue that cinema here emerges as a public horizon of proletarian self-organization and self-expression in Negt

02-C2205 8/17/02 3:37 PM Page 59

Incorporating the Underground

/

59

Figure 6. “Hello, America! Here is Europe!” The Tunnel. Courtesy of Filmmuseum Berlin—Deutsche Kinemathek.

and Kluge’s sense. Rather than recognizing cinema as a group-specific site of difference and autonomy, The Tunnel endorses in the final analysis nothing other than the Nazi remake of earlier forms of publicness. The film, in its final moments, supplants experience and difference instead of promoting their independent organization. It consecrates the advent of a unified public sphere whose function is to engineer consent from above, not to express critique from below.

Given the Americanist predilection of both Kellermann’s original novel and Bernhardt’s film, it might seem odd that the final sequence pictures Mac Allan’s American crew as passive onlookers of the European workers, a European sound cinema gone underground. Although the film’s narrative focuses entirely on the American digging efforts, it is the European team that effects the final breakthrough and, in so doing, assumes control over the terms of representation. Fear of penetration, we must recall, characterizes the overall body of Nazi film. Nazi features are preoccupied with drawing borders, shutting out foreign voices, bracketing sexuality, and containing media of exchange such as money in order to uphold both the purity of

02-C2205 8/17/02 3:37 PM Page 60

60

/

Hollywood in Berlin, 1933 –1939

German space and the “armored man’s self-preservation.”20 To propose a possible answer to this perplexing role reversal at the film’s end, one needs to take into consideration not simply the Americanism debates of the 1920s and 1930s but more specifically the German film industry’s attempt during the 1930s to challenge the foremost signifier of Americanism, Hollywood, on its own grounds. Like the majority of feature films produced during the National Socialist era, the film might aspire to become “readable in terms of classical narrative in much the same way as do Hollywood films of the 1930s.”21 On the other hand, however, the film prefigures the efforts of Nazi cinema to replace Hollywood with a domestic version of industrial mass culture. That Bernhardt, in the end of his Americanist fantasy, pictures America as the passive spectator of Europe prefigures the advent of a new media culture not in America but at the home front—a media culture in which moving images of bodies and voices serve the cause of political mobilization.22

Nazi film theorist Hans Traub proposed in 1933 that movement and rhythm are themselves tools of ideology and propaganda. What counts, according to Traub, is not sheer monumentalism but how a film offers shifting perspectives that draw the viewer into the depicted flow of crowds and overwhelm the audience with a sense of physical immediacy.23 In the final sequence The Tunnel combines Traub’s definition of ideology as movement with what Wolfgang Liebeneiner, as discussed in the previous chapter, understood as the principal task of German cinema, namely to convert film as sound film into a total work of art. If the newsreel sequence heroized the sights of modern America, the breakthrough scene in the end introduces German sound cinema as a viable, in fact, superior substitute for the attractions of Hollywood. In line with a long-standing trope of German anti-Americanism, the film in the end taxes America as an emasculated site of decadent consumption, a culture dominated by the “desires, tastes, and world views of women,”24 whereas Germany alone embodies a nation of resolute and recentered, of uncompromising and self-asserted, men. In the final shots the film literally consumes Hollywood, hoping to instill the popular fascination with American mass culture and technology with the power of a resolute vision and political movement.

n e t wo r k i n g t h e n at i o n a l c o m m u n i t y It has often been pointed out that radio played an important role during the Third Reich to deliver Nazi ideology and secure political control. Airwaves, particularly during the war, became a crucial medium to generate a sense of

02-C2205 8/17/02 3:37 PM Page 61

Incorporating the Underground

/

61

spatial continuity and bond the people’s emotions to their leaders. As David Bathrick has written, “Father and mother and newborn babe are brought together again in ether space, enabled by an apparatus that will link their individual destinies spatially and communally to the now expanded familial Reich.”25 Melodramas such as Schlußakkord (Final accord, 1936, Detlef Sierck) or Wunschkonzert (Request concert, 1940, Eduard von Borsody) have cast this ideological use of radio during the Third Reich into powerful cinematic images. Radios in these films, and the kind of music they transmit, signify the advent of a national community produced by the power of modern communication technology. Understood as a conduit to the deepest recesses of the German soul, radio here ties together individuals dispersed in geographical space; it is meant—in the words of a contemporary trade journal—“to leave the marketplace and return to the church, to a church, which will encompass all its listeners with the same atmospheric powers and which is capable of bridging distances just like the all uniting House of the Lord.”26

Radio was surely instrumental in elevating the Nazi movement to power.

In the electorate of 1932 Goebbels’s voice entered more than four million households through radio loudspeakers.27 Unlike the speeches of the democratic leaders, Goebbels and Hitler mesmerized their listeners with vocative resolve, visionary appeal, and fierce emotionalism. Yet, considering the fact that film practitioners at the same time were at pains to articulate voice and body into persuasive harmony, radio must have had something uncanny, particularly for a movement rallying against the functional differentiation of modern life and promising a resurrection of unified identities.

Radio, in the views of early commentators, destabilized space and unhinged temporal coordinates. It severed voice from body, split sounds and sights, fragmented the audience’s perception, and thus—potentially—ran counter to the Nazis’ call to recenter self and community.

The Tunnel echoes some of this early unease about the decentering force of radio. Contrary to Weimar science fiction films such as F.P.-1 antwortet nicht (F.P.-1 does not answer, 1932, Karl Hartl), in which wireless communication successfully bridged space and prepared narrative solutions, The Tunnel remains quite ambivalent about radio as a tool of mediating human voices. In the film’s hierarchy of media the wireless, in fact, comes in third.

It is shown as inferior to both the charisma of unadulterated speech and the technical reproduction of the voice through sound film. Radio, in Bernhardt’s film, fails to unite the masses in a new House of the Lord. Nor does it succeed in leaving the marketplace. According to The Tunnel it is only when attached to images, when elevated to the higher plane of sound cinema, that the mechanical recording of voices can serve the cause of mass mobilization.

02-C2205 8/17/02 3:37 PM Page 62

62

/

Hollywood in Berlin, 1933 –1939