Rather, it marked an eminently modern moment in American film history at which conventional notions of authorship and generic unity, of cultural distinctness and cross-cultural influence, seemed to loosen their grasp. As I will detail with regard to the work of Robert Siodmak, whose directorship in Germany, France, and Hollywood prior to 1943 shows no expressionist predilections whatsoever,8 film noir articulated diverse styles, cultural codes, and experiences into a performative and pluralistic hybrid. Understood as a heterotopia in Foucault’s sense, Siodmak’s work in Hollywood referenced the past as a symptom of present anxieties and concerns. Showcases of cultural absorption and redress, Siodmak’s film noirs invite us to think through the metaphoric exchanges between Weimar cinema and Hollywood as part of a history of productive misrecognitions and highly

06-C2205 8/17/02 3:38 PM Page 167

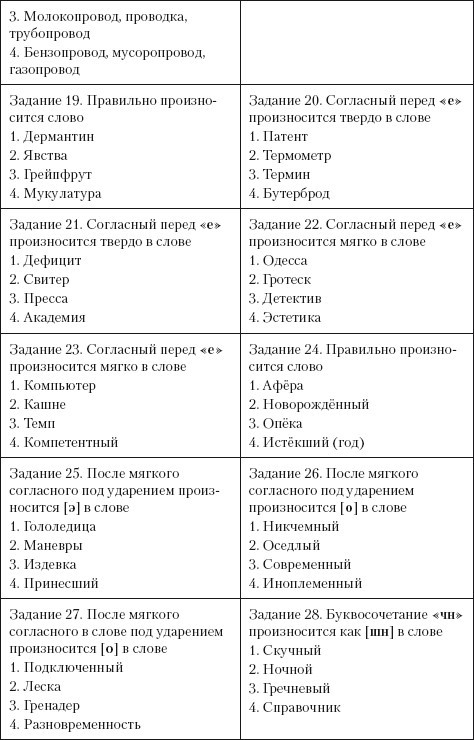

Berlin Noir

/

167

mediated identifications.9 They press us to think of film history as a space of multiple and nonlinear (over)determination, a space where present events may illuminate their own past but can never be directly deduced from it.

Siodmak’s most productive phase in Hollywood dates from 1943 to 1949. For most of this time under contract at Universal, Siodmak directed a series of features that hold privileged positions in virtually all textbooks on film noir (for example, Phantom Lady, Christmas Holiday, The Spiral Staircase, The Dark Mirror, The Killers, Criss Cross). During the process of becoming a celebrated director of film noir, Siodmak in some sense departed radically from his own beginnings during the Weimar period. Confronted with studio pressures, Siodmak may have recalled some aspects of German expressionist cinema—Weimar film’s vocabulary of anxiety and paranoia, of visual stylization and theatrical excess. But this reinscription was discontinuous to say the least. It resurrected a past that had never existed as such, and it reflected an imaginary other in the mirror of domestic traditions such as the hard-boiled detective novel or American cinema’s own experiments with chiaroscuro lighting since the 1910s.10 Yet it is precisely this calculated recreation of the past, the imaginary and nontrans-parent links Siodmak’s films entertain with German materials, that helps us better grasp the position of film noir and exile filmmaking in the 1940s. In focusing in particular on Phantom Lady (1943) and The Spiral Staircase (1945) this chapter argues that Siodmak’s exile films evidence his professional adaptability as much as they undo essentializing concepts of historical causality and cultural singularity. Siodmak’s success in film noir did not result from some kind of innate Germanness or authorial vision. Instead, it ensued from his competent immersion into studio filmmaking, his intuitive understanding of Hollywood production processes as manifestations of what Fredric Jameson calls structural causality.11 Films such as Phantom Lady and The Spiral Staircase urge us to conceptualize exile filmmaking in the contentious 1940s as a multilayered structure of semiautonomous elements whose relationships with one another were increasingly nontrans-parent and mediated. Siodmak’s Hollywood is one in which uncertain causes and ambiguous effects become engines of narrative development, of textualization. Siodmak’s work in Hollywood thus reveals that any historical reality is representable only as an absence, as a result of retrospective interpretation and reconstruction—that “history is not a text, not a narrative, master or otherwise, but that, as an absent cause, it is inaccessible to us except in textual form, and that our approach to it and to the Real itself necessarily passes through its prior textualization, its narrativization in the political unconscious.”12

06-C2205 8/17/02 3:38 PM Page 168

168

/

Berlin in Hollywood, 1939 –1955

If it is the task of the historian to make the past somehow present again, then part of this project is to play through different patterns of nonlinear determination in the narrative space of the historian’s reconstruction. If historical realities, in the final analysis, cannot be represented indeed, then one aspect of gaining access to the absence of the real is to reflect on the past’s own modes of symbolization and narrative emplotment. This chapter argues that part of the political unconscious of Siodmak’s film noirs is the confrontation with Nazi cinema and its Wagnerian ideologies of embodiment.

Siodmak’s films, I suggest, probe the composite character of modern identity not in order to yearn for some kind of prelapsarian state of immediacy but, on the contrary, to undercut any conversion of loss and fragmentation into fantasies of power and resolve. Whereas Nazi cinema tried to contain the migratory potential of voice and music, Siodmak’s films of the 1940s complicate our understanding of cinematic audiovision by probing both the technological and ideological dimensions of sounds and images onscreen. An adept expert in the use of sound effects since the early 1930s, Siodmak explores in his American work how cinematic audiovision may either—as in Nazi cinema—amplify anaesthetic fantasies of wholeness and self-presence or promote more decentered forms of subjectivity that recognize lack, fragmentation, and nonidentity as peculiarly modern sources of meaning. Although we cannot deduce Siodmak’s work from his German past, it is his German experiences that—like the psychoanalyst’s voice—may illuminate what drives the conscious and unconscious of his protagonists in Hollywood.

e x p l o r at i o n s i n n o n s y n c h r o n i c i t y Robert Siodmak’s career is often told as a narrative of ruptures and fly-by-night departures. In his autobiography Siodmak summarizes the most critical caesuras of his life as such: he left Germany the day after Hitler had come to power; he departed from Europe one day before the outbreak of World War II; and he turned his back on Hollywood a year before the introduction of Cinemascope.13 But to think of Siodmak’s career simply in terms of unwanted dislocations underestimates what steered him to success in the first place. He may have left Germany when Hitler came to power, but—unlike many other German film practitioners in exile—he did not have much difficulty inserting himself into the French and later into the American film industry. He may have left Hollywood when the studios embraced widescreen cinema to reclaim their former hegemony, but in previous decades it had been, for instance, the arrival of sound and of more sen-

06-C2205 8/17/02 3:38 PM Page 169

Berlin Noir

/

169

sitive film stock that had propelled him into new creative directions. Driven by an enormous hunger for personal success and aesthetic recognition, Siodmak lived out four careers (Weimar, France, Hollywood, postwar Germany) that all shared the same eagerness to face new challenges and transform the unknown into a source of inspiration. Rupture and displacement were the very stuff Siodmak’s successes were made of. Siodmak’s career as a filmmaker was a zigzag tale of masterful mimicry and visionary adaptation.

The exile’s state of displacement was his home, and the migrant’s desolation became the price for his relentless grasp for fame.

In a report to MGM in the early 1940s, Hollywood agent Paul Kohner introduced Siodmak as a director of great versatility and competence:

“Mr. Siodmak’s films, although mostly treating difficult subjects, are vividly realistic and possess the spell of imagination which is the principal element of entertainment. The best argument for Mr. Siodmak’s ability as a director is his pictures and I feel that he would be a definite asset to any production company.”14 Siodmak’s work prior to his arrival in Hollywood indeed evidenced a remarkable ability to fuse entertainment values with technical experimentation. In particular Siodmak’s response to the coming of sound contributed to his reputation as a pragmatic universalist, a zealous innova-tor eager to convert technological changes into new stylistic formulas. Although he had entered the scene of Weimar filmmaking with a silent feature, it was in the sound medium that some of his most striking accomplish-ments took place prior to the Nazi takeover. “A plain and mute shot,” Siodmak explained in 1930, “can be contrasted with different sounds so effectively that the effect of this scene is much stronger than for example the effect of the pure rhythm of images in a silent film.”15 Already in Siodmak’s first full-length sound film, Abschied (Farewell, 1930), speech, music, and atmospheric noises were brought into contrapuntal relations with the image track, achieving what Karl Prümm calls the film’s “perplexing multitextuality.”16 Contradicting all those who considered film sound redundant, Siodmak’s Abschied employed sound to multiply the film’s levels of signification and allow the viewer’s perception to migrate across the frame of the visible. Similar to Fritz Lang’s M or G. W. Pabst’s Kameradschaft, Siodmak’s early sound films such as Abschied, Der Mann, der seinen Mörder sucht (A man in search of his murderer, 1930), and Voruntersuchung (Preliminary investigation, 1931) rendered the new medium itself as the message. These films featured sound not simply as a means to support but to comment or expand on the image, to fragment or explode the visual field, and thus to enhance both the imaginative and the realistic possibilities of cinematic representation.

06-C2205 8/17/02 3:38 PM Page 170

170

/

Berlin in Hollywood, 1939 –1955

Siodmak carried his fascination with the sound medium through his six years in France to the Hollywood studio system. In particular his film noirs of the mid-1940s are replete with instances of multitextuality. They offer highly acoustical mise-en-scènes that frequently, to say the least, ripple the primacy of the image in classical filmmaking. Unlike Max Ophuls, that other exile virtuoso of film sound, Siodmak, throughout his Hollywood period, showed little interest in using the sound track as an “acoustical panorama,” an atmospheric texture offering thick descriptions of everyday experience.17 Instead, Siodmak’s use of sound relied mostly on principles of isolation, formalization, and stylization. He created hyperbolic collisions of sounds and sights that signify dramatic experiences of loss and fragmentation, outbursts of repressed desire and violence, but that at the same time explore narrative possibilities beyond the classical regime of closure and causality. The famous jamming session in Phantom Lady—an explosive interlude of frenzied jazz sounds and hyperkinetic images—may be the most stunning example of how Siodmak’s Hollywood films employ the acoustical to puncture the frames of image and narrative and in so doing broaden the spectrum of sense perception.

In this sequence drummer Cliff Milburn (Elisha Cook Jr.) leads his putative date, Kansas (Ella Raines), into an obscure basement, an extraterrestrial space excessively cut into ribbons of light and shadow (fig. 21). What follows is an extended theater of musical passion that clearly exceeds the narrative task to detail Cliff’s persona or highlight Kansas’s brave deception.

For a moment of unmitigated auditory and visual spectacle the film’s narrative in fact comes to a standstill as Cliff joins the practice of a jazz quin-tet and, kindled by Kansas’s erotic gestures, bursts into a delirious drum solo. Editing and camerawork in this sequence give formal impressions of Cliff’s tension-ridden performance. The camera’s canted perspectives emphasize Cliff’s violent unfastening of desire, and the ever-accelerating montage of images translates explosive rhythms into a compelling iconic language. The visual field itself thus seems drawn into a musical vortex of passion and desire. The camera affords no stable position outside of the spectacle. It cuts bodies into pieces and shows facial expressions from grotesque proximity, intensifying the basement’s claustrophobic design to the point of a virtual implosion.18

At first this sequence seems to employ jazz in an all-too-familiar manner: as a signifier of sex, ecstasy, and desire. African-American music here, we might argue, represents what dominant culture considers animalistic, unmediated, and uncontained. A closer look at the jazz interlude of Phantom Lady, however, should dispel this suspicion. The jazz sequence, in fact,

06-C2205 8/17/02 3:38 PM Page 171

Berlin Noir

/

171

Figure 21. Jazz, desire, and representation: Robert Siodmak’s Phantom Lady (1944). Courtesy of Filmmuseum Berlin—Deutsche Kinemathek.

foregrounds the very mechanisms of projection and exoticism according to which mainstream culture discursively constructs jazz as entirely nondis-cursive. A film within the film, the jamming session features white musicians donning the dress of black culture to express what dominant stereotypes render the bliss of being carried beyond oneself. Aroused by Kansas’s counterfeit, the rather feebleminded Cliff enters the basement, joins the band midway, bursts into an ecstatic solo, and then departs again without farewell or closure. In the role of the cunning enunciator of Cliff’s desire, Kansas thus allows the viewer to see to what extent jazz may function as a language of representation after all. Although she herself fakes desire and heat, she reveals the status of jazz as a signifying system that can be used for different constructions of agency. Jazz may isolate Cliff from discourse and transform his body into an object of audiovisual spectacle, but for Kansas it becomes a means not only to take command over Cliff but also to lay bare the role of the cinematic apparatus as a tool of signification and fantasy production.19

06-C2205 8/17/02 3:38 PM Page 172

172

/