When Washington was at Valley Forge, during the brutal winter of 1777-1778, it was alleged that he was overheard in prayer by a Tory-sympathizer, a Quaker named Isaac Potts. This man supposedly came across General Washington in prayer in the woods and then came home and declared to his wife, “Our cause is lost.” He feared that the rebels would win the war, because he heard their leader in earnest audible prayer and had become convinced there was no way that God would not honor that prayer.

Boller discounts this story as part of unreliable oral tradition.132 Earlier generations of Americans, however, accepted it as historically reliable. Consider, for example, the 1903 Episcopal Washington Memorial Chapel in Valley Forge built to commemorate the story; a 1928 two-cent U.S. postage stamp of Washington in prayer at Valley Forge; a 1955 stained-glass window of the scene in the Prayer Room in the U.S. Capitol building; and a bronze rendition of Washington’s “Gethsemane” in the Sub-Treasury Building in New York City.

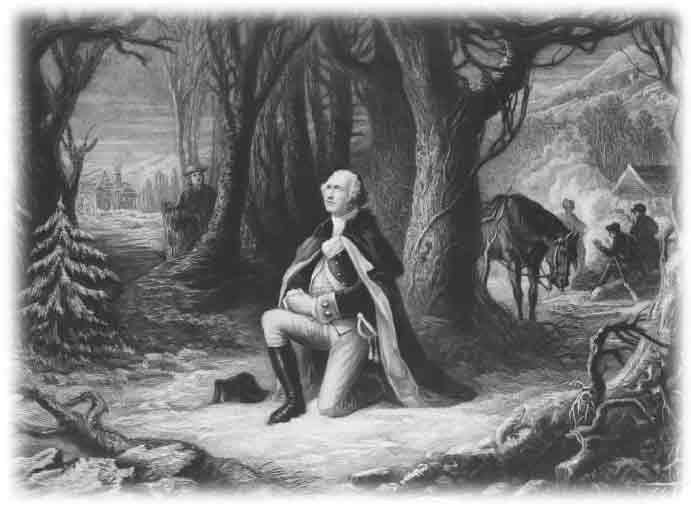

George Washington praying at Valley Forge

.

The eyewitness Isaac Potts can be seen illustrated behind the trees on the left side of this etching

.

Why does Boller think this story is apocryphal? In part, because of differences that exist in the traditional story. One version has the man’s name as Isaac Potts. Other versions have a different name for the Quaker as well as his wife. Moreover, the Potts family that owned the house, still known as Washington’s Headquarters, have no records that would indicate that Potts made a trip that winter to Valley Forge, where he would have had the occasion to have stumbled on Washington kneeling in the snow in private prayer.

As Boller presents it, there is no hard evidence that the story ever occurred. All we have is the mythic legend preserved in the unsubstantiated story told by the Reverend Mason Weems. Yet, Boller admits that there were others who gave evidence to the account.133 Rather than engage them, he simply dismisses them with his uncritical remark, “…scores of witnesses attesting to the event (many years later) have been dug up by champions of the story; and many details have been added by later writers to Weems’s original account. . . .The Valley Forge story is, of course, utterly without foundation in fact.”134

What is the extent of Boller’s proof? Only the words just cited. That is all he has to say about the subject that built a million dollar church, created one of the best selling postage stamps in history, is reflected on two U.S. government buildings, and prompted President Ronald Reagan to say, “The most sublime picture in American history is of George Washington on his knees in the snow at Valley Forge. That image personifies a people who know that it is not enough to depend on our own courage and goodness; we must also seek help from God, our Father and Preserver.”135 Doubt and criticism are good tools for the historian, but when they allow a historian to fail to do his work and to reach a scientifically justifiable conclusion, they are no longer tools, but expressions of a hostile, prejudicial philosophy.

Our purpose here is not to do the extensive research that would be required to demonstrate what elements of truth are extant in the oral history and accounts that have preserved the tradition of Washington’s prayer at Valley Forge. Moreover, our argument for Washington’s Christianity is not dependent upon the validity of this anecdote in any way. The evidence we have employed is built directly on Washington’s own words. However, we believe that a respectable, historical discussion of this matter at least requires an awareness of the information that Boller simply sweeps under the rug of his skepticism.

All told, there are five different individuals who gave an account of Washington praying at Valley Forge. They are: Reverend Mason L. Weems,136 Washington historian Benson J. Lossing,137 Reverend Devault Beaver,138 Dr. N. R. Snowden, who claimed to have heard it directly from Isaac Potts himself,139 and General Henry Knox.140

Could this story be true? By the strictest, critical standards of historical investigation, we cannot establish its validity. We have no letter from Washington or Isaac Potts declaring that this is what happened. There is no contemporary newspaper account that relates these facts. By the standards of oral history, however, it appears to have a legitimate claim for being considered as a possible historical event. Oral history recognizes that rigorous, critical, historical proof is not the only way history is preserved. It is one thing to say that an oral report of an incident cannot be proven by an eyewitness or a participant’s written report; it’s another thing to say it did not happen. The multiplicity of testimony and the claim of a remembered interview recorded for posterity suggest that something may well have happened in the snowy woods of Valley Forge.

Our purpose here is not to prove the story, but to show that Boller’s cavalier approach to the facts of oral history also reflect his lack of consideration of the written record of Washington and his contemporaries. So even though Boller asserts, “The Valley Forge story is, of course, utterly without foundation in fact,” we wish to determine what are the critical and historical facts that we do know about George Washington as a man of prayer? And what we know argues decisively that Washington prayed at Valley Forge, whether Isaac Potts saw him or not.

First, there is indisputable, written evidence from George Washington that he fervently prayed for himself and for the success of his army only months before the painful winter of Valley Forge. In a letter to Landon Carter that Washington wrote from Morristown on April 15, 1777,

Your friendly and affectionate wishes for my health and success has a claim to my most grateful acknowledgements. That the God of Armies may Incline the Hearts of my American Brethren to support, and bestow sufficient abilities on me to bring the present contest to a speedy and happy conclusion, thereby enabling me to sink into sweet retirement, and the full enjoyment of that Peace and happiness which will accompany a domestick Life, is the first wish, and most fervent prayer of my Soul.141

Clearly, Washington wanted the war to end and had already been longing to go home. If Washington fervently prayed for this before the sufferings of Valley Forge, it seems certain that he prayed at Valley Forge, when all he had to count on for victory was the bare hope that God might answer his prayers. To show that this was not a misstatement on Washington’s part, it is significant that virtually the same words were used by Washington just three days earlier in a letter to Edmund Pendleton,

Your friendly, and affectionate wishes for my health and success, has a claim to my thankful acknowledgements; and, that the God of Armies may enable me to bring the present contest to a speedy and happy conclusion, thereby gratifying me in a retirement to the calm and sweet enjoyment of domestick happiness, is the fervent prayer, and most ardent wish of my Soul.142

Second, there are dire circumstances of Valley Forge found in Washington’s description already quoted of the sufferings of his men that winter of defeat and despair. The capitol city of Philadelphia lay in the conquerors’ hands, and Congress had been forced to flee to Lancaster and York. Clearly, this was an occasion for the deepest groanings of prayer for a man of faith. Given that Washington’s life and writings show he practiced daily prayer, it is no stretch of historical credibility to affirm that Washington was praying at Valley Forge. The point here is that we don’t need the alleged Quaker to prove that General Washington was given to “fervent prayer.” His own pen tells us that such was the case.

Also, if we are looking for testimonies of Washington’s prayer life by those who observed it, why pursue Isaac Potts, when there are so many other historical examples that are readily at hand? There are other traditional accounts of Washington praying at Valley Forge beyond those that we’ve mentioned so far, such as his prayer for a dying soldier at Valley Forge.143 But we will not appeal to this account, even if it may have an element of authenticity. After all, we have already seen that there are over one hundred written prayers in Washington’s writings, which we have already addressed in the chapter on Washington and prayer. Beyond this, there are the historical affirmations that Washington was a man of prayer.

…it was Washington’s custom to have prayers in the camp while he was at Fort Necessity.144

He regularly attends divine service in his tent every morning and evening, and seems very fervent in his prayers.145

Throughout the war, as it was understood in his military family, he gave a part of every day to private prayer and devotion.146

… the Reverend William Emerson, who was a minister at Concord at the time of the battle, and now a chaplain in the army, writes to a friend: There is great overturning in the camp as to order and regularity. New lords, new laws. The Generals Washington and Lee are upon the lines every day. New orders from his Excellency are read to the respective regiments every morning after prayers.147

Some short time before the death of General Porterfield, I made him a visit and spent a night at his house. He related many interesting facts that had occurred within his own observation in the war of the Revolution, particularly in the Jersey campaign and the encampment of the army at Valley Forge. He said that his official duty (being brigade-inspector) frequently brought him in contact with General Washington. Upon one occasion, some emergency (which he mentioned) induced him to dispense with the usual formality, and he went directly to General Washington’s apartment, where he found him on his knees, engaged in his morning devotions. He said that he mentioned the circumstance to General Hamilton, who replied that such was his constant habit.148

…when …Elizabeth Schuyler was a young girl, before her marriage to Alexander Hamilton, she was with her father, General Philip Schuyler, one of Washington’s aides, at Valley Forge, and saw the terrible sufferings of our men, and heard at that time Washington’s fervent prayer that all might be well.149

Third, Washington prayed in the winter following Valley Forge. Although Washington’s soldiers faced great sacrifice, in this instance provision came to meet the needs of the troops. And this prompted his “ardent” prayer. He wrote to Eldridge Gerry, from Morris Town on January 29, 1780,

With respect to provision; the situation of the army is comfortable at present on this head and I ardently pray that it may never be again as it has been of late. We were reduced to a most painful and delicate extremity; such as rendered the keeping of the Troops together a point of great doubt.150

Washington had not forgotten how difficult it was when the army’s needs had not been met. He prayed that the painful circumstances would not be repeated, though the need had been met. If he prayed in a time of provision, would it have been likely that he would not have prayed in the midst of great need in the first instance? Would we not expect him to have prayed, especially since the record of his consistency in prayer was written repeatedly in undeniable, historical records?

Finally, we can verify one time when Washington prayed at Valley Forge from his own writings. This is found in his General Orders for April 12, 1778, that called for prayer following the Congressional Proclamation.

The Honorable Congress having thought proper to recommend to The United States of America to set apart Wednesday the 22nd. instant to be observed as a day of Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer, that at one time and with one voice the righteous dispensations of Providence may be acknowledged and His Goodness and Mercy toward us and our Arms supplicated and implored; The General directs that this day also shall be religiously observed in the Army, that no work be done thereon and that the Chaplains prepare discourses suitable to the Occasion.151

CONCLUSION

The last time Washington wrote the phrase “sacred cause” was as his men were heading for Valley Forge. It was as if the sacred cause had been internalized, or become a reality. The next dramatic moment when he would return to this powerful image would be in his First Inaugural Address where his “sacred cause” had become the “sacred fire of liberty.” Not only had freedom’s holy light not gone out, but it was burning brightly ready to ignite other hearts and other nations.

So could a Quaker have found Washington on his knees in secret prayer, in the snow, at Valley Forge? If we could have asked the opinion of the colonial Lutheran minister Reverend Muhlenberg, he would have not have found the claim unbelievable about the one who was “graciously held” in God’s “hand as a chosen vessel.”

Thus, the question can no longer really be whether Washington prayed at Valley Forge and was seen by a pacifist Quaker who converted to the American cause. Those events may have happened, but they cannot ultimately be proven. The question instead must be whether Washington prayed at Valley Forge. The only possible answer consistent with all that we know is “yes.”

But perhaps the more relevant question is why scholars are insistent on telling the truncated secular version of Washington’s encampment at Valley Forge? Why would they tell the story of Washington’s great triumph in the battle over doubt and despair without reference to his “sacred cause?” without reference to Washington’s faith in Jehovah? without reference to his call for his men to be Christians? Were not these the things that produced “the sacred fire of liberty” that kept his men united in spite of their extreme exposure to the frigid winter winds of Valley Forge? Why then would scholars censure the sermon of Chaplain Israel Evans made at Valley Forge when it had the full approval of Washington? We can no longer tell the story of the Valley Forge encampment without looking on “his excellency General Washington” as Israel Evans admonished,

... Look on him, and catch the genuine patriot fire of liberty and independence. Look on him, and learn to forget your own ease and comfort; like him resign the charms of domestic life, when the genius of America bids you grow great in her service, and liberty calls you to protect her. Look on your worthy general, and claim the happiness and honour of saying, he is ours. Like him love virtue, and like him, reverence the name of the great Jehovah. Be mindful of that public declaration which he has made, “That we cannot reasonably expect the blessing of God upon our arms, if we continue to prophane his holy name. Learn of him to endure watching, cold and hardships, for you have just heard that he assures you, he is ready and willing to endure whatever inconveniencies and hardships may attend this winter. Are any of you startled at the prospect of hard winter quarters? Think of liberty and Washington, and your hardships will be forgotten and banished.152

Perhaps the reason the secularists have forgotten the inseparable connection between Washington’s “sacred cause,” his “patriot fire of liberty,” and his “all wise and powerful Being” is because they have been so intent on finding a Deist Washington. As a result of their quest, they clearly have not shared “the first wish of his heart.” This wish was “to aid pious endeavours to inculcate a due sense of the dependance we ought to place in that all wise and powerful Being on whom alone our success depends.” General Washington was here referring to Jehovah, the God of the burning bush, and the inexhaustible energy of the “sacred fire of liberty.”

TWENTY