She came down to dinner a few minutes later with a calm, serene face, on which was no hint of her recent emotion, and she managed to keep the table conversation wholly in her own hands, telling Mr. Tanner about her home town and her father and mother. When the meal was finished the minister had no excuse to think that the new teacher was careless about her friends and associates, and he was well informed about the high principles of her family.

But West had retired into a sulky mood and uttered not a word except to ask for more chicken and coffee and a second helping of pie. It was, perhaps, during that dinner that he decided it would be best for him to preach in Ashland on the following Sunday. The young lady could be properly impressed with his dignity in no other way.

CHAPTER XII

When Lance Gardley came back to the Tanners' the sun was preparing the glory of its evening setting, and the mountain was robed in all its rosiest veils.

Margaret was waiting for him, with the dog Captain beside her, wandering back and forth in the unfenced dooryard and watching her mountain. It was a relief to her to find that the minister occupied a room on the first floor in a kind of ell on the opposite side of the house from her own room and her mountain. He had not been visible that afternoon, and with Captain by her side and Bud on the front-door step reading The Sky Pilot she felt comparatively safe. She had read to Bud for an hour and a half, and he was thoroughly interested in the story; but she was sure he would keep the minister away at all costs. As for Captain, he and the minister were sworn enemies by this time. He growled every time West came near or spoke to her.

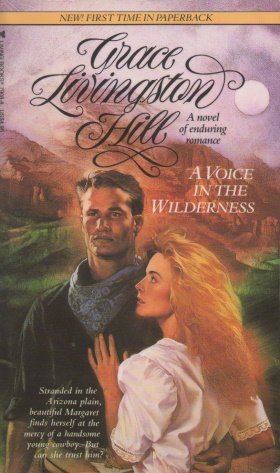

She made a picture standing with her hand on Captain's shaggy, noble head, the lace of her sleeve falling back from the white arm, her other hand raised to shade her face as she looked away to the glorified mountain, a slim, white figure looking wistfully off at the sunset. The young man took off his hat and rode his horse more softly, as if in the presence of the holy.

The dog lifted one ear, and a tremor passed through his frame as the rider drew near; otherwise he did not stir from his position; but it was enough. The girl turned, on the alert at once, and met him with a smile, and the young man looked at her as if an angel had deigned to smile upon him. There was a humility in his fine face that sat well with the courage written there, and smoothed away all hardness for the time, so that the girl, looking at him in the light of the revelations of the morning, could hardly believe it had been true, yet an inner fineness of perception taught her that it was.

The young man dismounted and left his horse standing quietly by the roadside. He would not stay, he said, yet lingered by her side, talking for a few minutes, watching the sunset and pointing out its changes.

She gave him the little package for Mom Wallis. There was a simple lace collar in a little white box, and a tiny leather-bound book done in russet suède with gold lettering.

"Tell her to wear the collar and think of me whenever she dresses up."

"I'm afraid that'll never be, then," said the young man, with a pitying smile. "Mom Wallis never dresses up."

"Tell her I said she must dress up evenings for supper, and I'll make her another one to change with that and bring it when I come."

He smiled upon her again, that wondering, almost worshipful smile, as if he wondered if she were real, after all, so different did she seem from his idea of girls.

"And the little book," she went on, apologetically; "I suppose it was foolish to send it, but something she said made me think of some of the lines in the poem. I've marked them for her. She reads, doesn't she?"

"A little, I think. I see her now and then read the papers that Pop brings home with him. I don't fancy her literary range is very wide, however."

"Of course, I suppose it is ridiculous! And maybe she'll not understand any of it; but tell her I sent her a message. She must see if she can find it in the poem. Perhaps you can explain it to her. It's Browning's 'Rabbi Ben Ezra.' You know it, don't you?"

"I'm afraid not. I was intent on other things about the time when I was supposed to be giving my attention to Browning, or I wouldn't be what I am to-day, I suppose. But I'll do my best with what wits I have. What's it about? Couldn't you give me a pointer or two?"

"It's the one beginning:

"Grow old along with me!

The best is yet to be,

The last of life, for which the first was made:

Our times are in His hand

Who saith, 'A whole I planned,

Youth shows but half; trust God: see all, nor be afraid!'"

He looked down at her still with that wondering smile. "Grow old along with you!" he said, gravely, and then sighed. "You don't look as if you ever would grow old."

"That's it," she said, eagerly. "That's the whole idea. We don't ever grow old and get done with it all, we just go on to bigger things, wiser and better and more beautiful, till we come to understand and be a part of the whole great plan of God!"

He did not attempt an answer, nor did he smile now, but just looked at her with that deeply quizzical, grave look as if his soul were turning over the matter seriously. She held her peace and waited, unable to find the right word to speak. Then he turned and looked off, an infinite regret growing in his face.

"That makes living a different thing from the way most people take it," he said, at last, and his tone showed that he was considering it deeply.

"Does it?" she said, softly, and looked with him toward the sunset, still half seeing his quiet profile against the light. At last it came to her that she must speak. Half fearfully she began: "I've been thinking about what you said on the ride. You said you didn't make good. I—wish you would. I—I'm sure you could—"

She looked up wistfully and saw the gentleness come into his face as if the fountain of his soul, long sealed, had broken up, and as if he saw a possibility before him for the first time through the words she had spoken.

At last he turned to her with that wondering smile again. "Why should you care?" he asked. The words would have sounded harsh if his tone had not been so gentle.

Margaret hesitated for an answer. "I don't know how to tell it," she said, slowly. "There's another verse, a few lines more in that poem, perhaps you know them?—

'All I never could be, All, men ignored in me,

This I was worth to God, whose wheel the pitcher shaped.'

I want it because—well, perhaps because I feel you are worth all that to God. I would like to see you be that."

He looked down at her again, and was still so long that she felt she had failed miserably.

"I hope you will excuse my speaking," she added. "I—It seems there are so many grand possibilities in life, and for you—I couldn't bear to have you say you hadn't made good, as if it were all over."

"I'm glad you spoke," he said, quickly. "I guess perhaps I have been all kinds of a fool. You have made me feel how many kinds I have been."

"Oh no!" she protested.

"You don't know what I have been," he said, sadly, and then with sudden conviction, as if he read her thoughts: "You do know! That prig of a parson has told you! Well, it's just as well you should know. It's right!"