“But you think that he might have been sleeping with Marjorie Persky and—”

“Why not? Read the history books—her husband was lavender as they come.”

“What did Reynaldo say about her?”

She shrugged. “We were kids. We were into La Revolucion and Rey-Rey just embodied it, because he was so free-spirited. I think this lady was part of that—showing a grown-up white woman what’s what.”

“So,” I said, “you think her husband might’ve caught Rey and—”

She smirked with displeasure, her back to the door as if she was blocking my entrance. She said, “You think it’s funny.”

“That isn’t true.”

“No—but what I mean is, if he hadn’t been murdered, you would think it was funny.”

“Why? What makes you say that?”

With an angry yank, the professor hoisted the valise over her shoulder and opened the door. “The young Mexican hombre and the horny gringo lady, the MILF. He brings around the loco weed, she seduces him. It’s like a bad eighties movie.”

“When you put it that way—”

“But it’s not funny. It’s not funny at all. Don’t you see, that is where the crime begins.”

“Maybe you’re right, maybe I don’t see. How does murder start there?”

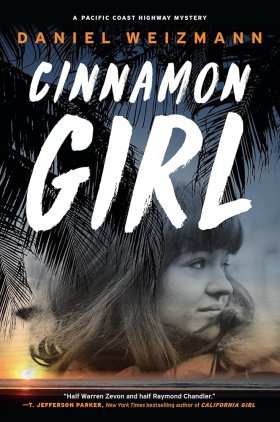

“Because whoever she was, she had all the power. A young, short guy like Reynaldo, with his whole being tied up with machismo, Mister Drummer Man, the Mexican Keith Moon, out to prove—no, don’t make a face. I have thought about this for years now, decades. I don’t know if Mr. Persky killed him or some other goon did or what. Just because Herbert Persky was gay doesn’t mean he wasn’t possessive—she was his wife. Or maybe it was the daughter, Little Miss Cinnamon, the band’s little mascot. Or the singer—not a well man. But whoever, however—Rey-Rey was already put in a compromised position just being there and that is on Mrs. Lily White. She was no grown-up. She didn’t give a rat’s ass what happened to my cousin the minor. She just did the white person thing and said, ‘My pleasure comes first.’ He was her gardener, literally—at your service.”

She opened the door and stepped inside. “That’s right,” she said over her shoulder. “The expendable amigo—she set him up for the kill.”

“Professor,” I said. “Ms. Durazo. Devon Hawley Junior was murdered last night. I went to see him, I…found his body. The police are…I was questioned, they…”

She stared me down, near frozen—her upper lip trembled once.

Then she slammed the door in my face.

14

14

On Thursday morning, I went to Devon Hawley Junior’s funeral uninvited. From the nearest faraway bench on Forest Lawn’s long green slope, I peered through mini-binocs over my shoulder as little black-clad bodies gathered on the tilted horizon, nestled by a very man-made running rock stream. The day was hot but overcast and the crowd was light—maybe twenty people in all. All I could see were the unfocused backs of heads. The black-robed priest gesticulated like a listless car dealer, pitching his prayer like he was selling the extra-long black box. For a man who loved miniatures, Devon Hawley had been a giant. Maybe that was the point.

No weepers that I could see—the whole affair played like a have-to ritual. This peculiar distance brought me back to the day of my uncle’s funeral, how I couldn’t bear to see him lowered into the ground so I hid at a coffee shop counter, jittery and bewildered. And it was bewildering, this life that ends in death, this game of hot potato. Here I was, stalking a total stranger’s funeral, incognito and alone, yet now I could sense Herschel beside me, looking over my shoulder surveying the scene. The dead don’t go far. They hover like nurses on-call. With some, you can get closer than you ever could in life.

A team of Mexican laborers in matching long sleeves approached. How they bore the heat was the real mystery. Shovels caught the sunshine as they thudded ground. Goodbye, Devon Hawley Junior, builder of cities, player of songs.

I got up and leaned on a tree for a better angle. Nobody familiar, no sight of Hawley Senior or Marjorie Persky or Socorro Durazo, but one old reed of a cocoa-toned guy caught my eye because of his gray Jew-fro and his rock-and-roll threads—black Harley Davidson tee, black jeans, black Converse, silver dog tags. As the crowd dispersed, I shoved the binoculars in my windbreaker pocket and moseyed slow down the hill, hoping to line up with him and get a closer look.

“Excuse me.” I pointed. “Are you Jeff Grunes?”

He stopped in his tracks, went skeptical. “Who are you?”

Flowing fields of plaques surrounded us in every direction. His dark skinniness cut a dramatic figure against the green. He was early sixties at least, an aging half-Black, half-Jewish rock dude in thick prescription glasses, but the spark of life in him was still jumpy, youthful, looking for a place to spread. Behind the heavy lenses he had the kind of learned eyes you know have read everything—cognitive theory, poli-sci, The Life Cycles of Empire. No People magazine for this guy.

“I’m Adam,” I said. “I’m a Daily Telegraph fan.”

“No, you aren’t,” he said, matter-of-factly.

“Well—I’m working for Charles Elkaim.”

“Ah, one of those. Good luck on that.” He turned and made for his car in the glaring sun. I followed.

“Must have been a rough day today,” I said, “saying goodbye to an old friend.”

“Yeah, not exactly. More like…a lifelong enemy.”

“Really?”

“Everybody’s got one. Hawley was mine.”

“So you two haven’t been in touch?”

“Not since Bush Senior was president.”

“But how did you know about the funeral?”

“I kept tabs. Old band members do that.” He snorted. “What the hell’s the internet for, anyway?”

“Mr. Grunes, if you would just—”

“You know you’re like the eighth person that’s tried to figure this shit out, right?”