And it was her.

I froze in my tracks, ears burning, paralyzed for one long second—

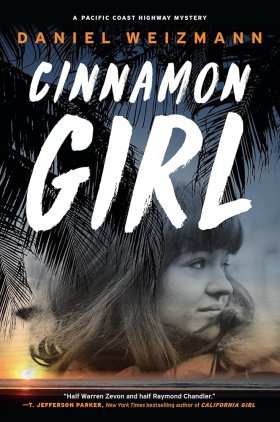

Behind the counter, rummaging through a wooden wine box filled with costume jewelry, it was really her. The freckle-faced teen from the trip to Disneyland, Emil’s girl, Cinnamon, now a middle-aged woman. The red luster gone from her hair, she was auburn-gray, looked permanently tired, but she was beautiful.

My heart raced as I turned and did a little fake browse through a rack of “Hang In There” cat posters, admonishing myself for not having a plan, but what kind of plan could I have? An upside-down white kitten stared back at me and the world came to a dead stop, like when you’re in the presence of a celebrity you’d never dare approach. With great force I had to yank the pull cord within, to stop the busload of questions rushing forward: Was she—? But did she—? How did she—? And why was—? But I did look back at her over my shoulder and she caught me, our eyes met. She had one of those faces, one of those smiles that radiates ease through a wistful little silent inner laugh. It was a Renaissance face—the Madonna, about to crack up.

“Everything over on that right wall is thirty percent off. Lotta cool records and old rock tees.”

There was a funny, lilting chirp to her voice. It was a teenager’s voice, coming out of a fifty-something woman. Her kindness pained me, and for one brief second I considered turning around and going…out the door, home, anywhere. But my heart thumped, and I reached into a discount bin and picked up an orange fuzzy ball with googly eyes, maybe the tackiest thing in the whole damn joint.

“You like that?” she said with a curious grin.

I looked at it and looked at her.

I said, “You’re not gonna believe this, but you and I went to Disneyland together.”

Crooked smile. “That’s a hell of a pickup line.”

I shook my head a little. “I’m not kidding. You used to date my next-door neighbor, Emil. Emil Elkaim.”

Now she looked right through me, wheels spinning double-time.

Cold: “I don’t know that name.”

I smiled, to soften the blow. “The heck you don’t.”

Turning back to her wine box, pulling a long string of fake pearls, she said, “You must have me mistaken for someone else. I get that a lot—”

“We went in a convertible fiberglass MG. Your nickname’s Cinnamon. Was Cinnamon.”

Through gritted teeth, she said, “Steno pool.”

Three of the dogs snapped to attention, stared me down with caution. One started growling—a nasty-looking dark shepherd, hot to show teeth. On instinct, I raised my hands.

“I don’t mean any harm.”

“I don’t know you,” she said coolly. “And I think you should leave my store.”

“But I know you.” I spoke super slow, hands in the air, one eye on the dogs. “You’re Cynthia Persky, manager of The Daily Telegraph.”

Now out of nowhere, without a command, one fat pitbull got closer to my heel, and the very impatient-looking shepherd knelt to lunge position. My adrenaline was pumping haywire.

“What do you want?” she said with undisguised disgust.

“Please tell these guys to back off,” I said. “I’ve got no reason to turn you in or expose you or whatever. That won’t help me at all.”

“My husband will be back soon. He doesn’t—he—”

“I understand.”

“No, you don’t. He doesn’t know anything. You need to leave.”

“You’ve got to talk to me.”

“I can’t.”

“But you have to. Otherwise, I’ll have to tell him…” I shrugged. “Everything.”

She spat out some gibberish word and double-clapped. Disappointed, the hounds slumped away. One cocky terrier wandered past me. My hands dropped and I breathed relief. But she was livid.

Through gritted teeth, she said, “I can’t talk here.”

“Devon Hawley Junior was murdered last week.”

She kept one eye on the door. “I heard that. Who are you and what do you want?”

“I’m Adam. I used to live across the street from Emil. You babysat me and my sister, we went to Disneyland in Emil’s MG and—I’m from the old neighborhood.”

She closed her eyes, shook her head. “Please go away.”

All around me, the dogs, my former enemies, struggled to read the moment.

At that very second the bell rang and I angled fast, fake-browsed the Mickey phone. A tall, burly, tattooed man with a long gray beard and a biker’s cut lumbered in with a cardboard box. Her whole countenance changed—she moved toward him with fake morning ease, relieved him of the box, and gave him a kiss.

“Baby,” she said, “take those to the back room.”

“But they aren’t sorted.”