“Deal.”

29

29

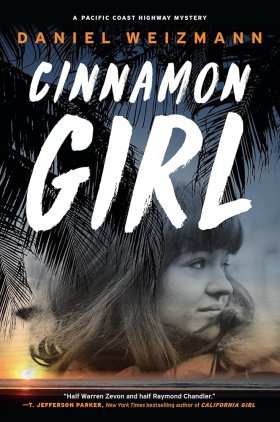

Cinnamon hung her head. The bar was really bustling now, the Keack exotica piped in over the chatter and the yuks.

“All of us,” she said, “were part of Dr. Bahari’s thing.”

“What…thing is that?”

“Dr. Aharon Bahari—he’s a psychiatrist, or at least he was. He ran this workshop, the Mind-Life Actualization Seminar for Teens. He’d written this book called Aggressive Positivity, and he was everywhere. ‘Harness the power of consciousness.’ For teens. And we—took the bait.”

I flashed on Sandoz and the after-school seminar he attended. “But…was it a cult?”

“Not exactly. But it wasn’t not a cult, ya know what I mean?”

“Not really.”

“Bahari’s trip was all about…changing the way you think. You had to, like, completely embrace the program—no halfway.”

“How’d the band find out about it?”

“Mickey was already there, but—” She smirked with humiliation and pointed at herself. “I talked the rest of them into doing the orientation—my dad read about it somewhere and I got all psyched to check it out. The band were mostly into it, too—except Rey-Rey, he thought it was jive. ‘You are fucking lost, all of you. And this shit ain’t rock and roll.’ ”

“Wow.”

“Yeah, wow is right, it’s like he saw what was coming. Anyway, Bahari loved that the guys were in a band. And eventually it came out that he had designs to be in the record business.”

“Get rich quick scheme?”

“Oh, he already had money, he was loaded. I mean, he was a big deal back then.”

“So what was it about?”

“At the time I thought he was just…getting off on the aggressive positivity of it all. I was hypnotized. But now I see—here’s this guy, all charismatic, he can hypnotize a whole audience. But he’s still an immigrant, right? The little man from Cairo. Definitely not in-crowd. And I think he craved that…that rock and roll glamour, and all that comes with it. He thought—you know, with these cool young dudes, there’ll be an overflow—of razzmatazz. They’ll all hop on a Lear jet with a bunch of models and head for the Bahamas or whatever, count their platinum records.”

“He really thought that’s where things were heading?”

“Oh, yeah. Bahari went bananas when he heard them rehearse. He bought us a brand-new Dodge Ram, opened up a charge account at Guitar Center. And he did make it seem like we were going places. He’d study the Billboard charts like they were a playbook and come back to the band with all these big ideas—he could be very seductive. He played us what he called doppelgangers—records to aspire to, right? It wasn’t completely different, that was his genius. He found the place where, like, The Daily Telegraph could be a little more modern, more up. ‘No more blues’—that was one of his mottos, ‘The blues are for losers.’ Lame—but he was so driven, it was hard not to get sucked in. And his first order of business was to get rid of Rey.”

This landed like a thud between songs in the suddenly quiet bar. She turned to face me.

“Who replaced him?”

Dryly, she said, “A Roland TR-808 drum machine.”

“Well, did the band protest?”

“Nope—and I didn’t either. I mean, we loved Rey-Rey, he was family, but the truth was, he wasn’t the world’s greatest drummer. So when Bahari told us he didn’t need to be a part of the recording—”

She shrugged.

“Was Rey pissed?”

“Not at first, he didn’t have the chance. He just…wasn’t invited to the sessions. But the other guys were completely sold, and Bahari especially doted on Emil, almost lived through him. The full-on Svengali trip. Two foreigners, taking over America—and it all happened so fast. Suddenly one day after school we’re in these offices in Century City, up on the fifteenth floor, the next week we’re tracking at Sunset Sound like we’re Fleetwood Mac or something. I mean, what are you gonna say? No? David Bowie was literally rehearsing in the next room over.”

“Wow,” I said. “So Bahari was really pushing for the big time.”

Cinnamon’s eyes went catlike with candor.

She shook her head. “It was me, Adam, okay? I was the crazy one. I was the one pushing. From the second I smelled fame and fortune, I was transformed. I got them tangled up with this weirdo and worked it one hundred percent, night and day. I fired up the fantasy, sold them his vision—I was relentless.”

She pointed at her own heart. “Everything that followed—is on me.”

“Okay, wait a sec, you wanted what was best for your band, that’s not a crime. And what makes you think this Bahari guy had anything to do with Durazo’s murder?”

She didn’t answer, not right away. A drunken silence set in between us, a wedge, but I understood—to me this was a story of long ago. To her it was a powder keg of shame right in the here and now.

“Between us?” she said.

“I swear it.”

“I don’t remember everything.” She scooted back into the booth and turned her profile to me, like a penitent at confession. “It’s like, I’ve been over this chain of events so many times, all I’ve got left is my own playback.”

“I get it. That’s how it is.”

“Anyway, one night, about two weeks before Rey was murdered, I saw him. I was coming back from the recording studio alone, I had this little back entrance to the house, just past my mom’s bungalow, like, 2:00 a.m. on a school night. And while I was fiddling with the keys, Rey-Rey stepped out of the shadows—practically gave me a heart attack. I guess he’d been with my mom that night, but now he was furious. Raging on me about cutting him out, lying to his face, all of it. He said I’d let this evil businessman change their music, break up the family. I mean, he was totally flipping out. And even worse was I could tell he was really hurt. He went on this crazy rant about how he had been spying on Dr. Bahari and…he found out about all these supposed questionable businesses—VD clinics, fake arcade games, euthanasia, all kinds of shady shit. I didn’t know if any of it was true, but Rey was on a rampage. He said…he said he was going to…step to Bahari and…put him in his place, something like that. He said—”

Just then Cinnamon’s eyes went wide—crazy wide, staring past me.