*

Part of me is dead. Killed by a self-destructive child, a psychopath with no empathy or concern for the lives of those with whom she shared a body. Part of me is dead, and there’s no way to get her back. We’ll never plant flowers again.

Part of me is dead, but she left something behind.

Eli.

Eli, we named our son, my Other and I. He’s not as bad, now that Emily is gone. Somehow Em’s death brought us closer together. Team David. Team Delacroix. It never occurred to me that he might hate Em’s Other as much as I did.

But we both love Eli, and that would make Em happy, I think. She’d want me to take care of him. She’d want both of us to take care of him.

Em lives on in him, and in me, and somehow in my Other too. She lives on in the lilies that we planted over the years, and the crease on her side of the mattress. She lives on in the smell of grapefruit and cigarettes.

Part of me is dead, but she isn’t gone. She’s still in the lilies out front, and in Eli’s chiffon pajamas. She’s still in the flannel sheets. She lives on in my memory. She lives on in the way she brought my Other and I together.

I can’t see her from here, but she isn’t gone.

Daniel Rosen writes speculative fiction and swing jazz in Minnesota, smack dab in the middle of North America. In between various fictions, he spends his time sprawled lazily with two cats and a lady. You can find him on twitter @animalfur, or at his website: http://rosen659.wixsite.com/avantgardens

Incoming

Thomas Clark

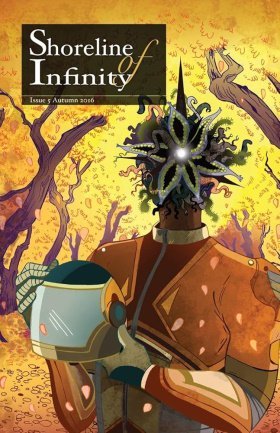

Art: Dave Alexander

Andy had just got off to sleep when it started again. It was getting to be every night now. He staggered out of bed, pulled his wax jacket on over his pyjamas. It could only have been three o’clock. Blearily, he stared at the Daedalian knots of his laces, tucked them down into the sides of his shoes. The close lights were broken, but the stairwell was already bright with open doors.

Andy had just got off to sleep when it started again. It was getting to be every night now. He staggered out of bed, pulled his wax jacket on over his pyjamas. It could only have been three o’clock. Blearily, he stared at the Daedalian knots of his laces, tucked them down into the sides of his shoes. The close lights were broken, but the stairwell was already bright with open doors.

“Mornin, Mrs. McGraw,” he shouted at the first door. Mrs. McGraw glowered at him, her weathered fist clasping shut her nightie like a brooch.

“Ah’ll gie ye morning! It’s a bloody disgrace, so it is,” she said, “There’s ma man daein mornins and he cannae get a wink o sleep.”

“Ah ken, ah ken,” Andy said, “Ah’m just away doon tae see aboot it.”

“Aye, well, when ye see him ye can tell him fae me …”

The noise, a continual low hum which shook the windows in their settings, suddenly redoubled, driving out all competing sounds. As he passed down through the stairwell, Andy tried not to notice the faces that stared lividly at him from the cracks of doors, the horrific writhings of their silent mouths. By now the noise was so loud that his eyes quivered in their sockets, and the close had the freakish appearance of double exposed film, an art-house installation for the criminally insane. “Sorry, sorry, sorry,” he found himself whispering as he shuffled past the doors, each framing a scene of suspended domesticity warped into something grotesque.

Outside, on the street, it was just as bad. Fractals of window-light pocked the low clear night, and the noise boomed through the narrow roads as they sunk towards the fields. As he walked along, Andy took a glance at the town hall spire. The clock was usually wrong, but it was certainly well past four. On the farms beyond Hawick, hired hands were already rising: Bulgarians and Poles who washed their faces in freezing water and listened with wonder to the sound, which could be heard as far as Branxholme Castle. It wasn’t until the valleys towards Galashiels that the noise finally passed beyond the range of human hearing, although the Jedburgh dogs still whined, and the sheep in Selkirk bleated sympathy. No-one knew.

“It’s not on, Andy, ah’m tellin ye,” Johnny McEwan roared out of his window, “Ah’m on the phone tae the cooncil first thing. As if it’s no bad enough UHRRRR”

Johnny threw his hands to his ears, but Andy knew from experience that nothing short of industrial grade ear muffs could block out this new noise: a long metallic shriek like a thousand rusty brakes. As the old man fell to his knees groaning, Andy pointed at an imaginary watch.

“Ah ken, Mr. McEwan, ah ken,” he shouted, “Ah’m just away tae tell him. It’s past a joke, this.”

By the time Andy had turned the corner onto the high street, the noise had stopped, lingering only in the high arches of the town walls, like a trapped bird trying to get out. D-CON, who had never shown the slightest bit of interest in it before, was crouched down next to the 1514 Memorial, scanning its inscription raptly. Darkness once again had settled.

“Like butter widnae melt, eh,” Andy said, “Whit’s the game here then, pal? Whit’s wae aw the noise?”

D-CON looked down at Andy with an immoderate start, as if only just noticing him.

“WHY ANDREW, I WAS …”

“Shh! Shh!” Andy whispered, the concrete shifting tectonically beneath his feet. The robot started again.

“APOLOGIES, ANDREW. WHAT NOISE?”

Andy screwed up his face.

“What noise? You got selective super-hearing all of a sudden? You’re at it, big man. Ah’ve telt ye wance, ah’ve telt a hunner times—when it gets dark, folk are tryin to sleep.”

“ANDREW, I CANNOT SLEEP.”

“Name o God … Whit, you want me to sing you a lullaby?”

“I …”

“Ah’m jokin,” Andy said hastily, “Ah ken whit you mean. But look, if you’re no able tae sleep at night, can you no just dae whit everybody else does an watch the telly or somethin? Get any channel ye like wae aw that gear stickin oot yer heid. Ah mean … och, here we go.”

A Volvo driving the wrong direction up the one-way street came to a sudden halt across the road. After a moment’s struggle, a fat man with unkempt hair and a provost’s chain over his nightgown wrangled his way out from under the steering-wheel and waddled over towards them. The backs of his slippers made a soft padding noise on the tarmac.

“Right, Andy! Whit’s going on here? Giein ye any problems, is he?”

“Naw, Davie, it’s just ...”

“This is no good enough, Andy. It’s needing nipped in the bud, like. Bloody robot getting the run of the place. Honest tae God.”

Davie squinted in D-CON’s direction. There were marks on either side of his nose where his glasses normally sat. He shook his head.