“We can leave.” Melano blurted out, “Just let us go: we’ll go all the way to the other side of the galaxy if—”

“—I’m afraid it doesn’t work like that,” my double said. “Entanglement’s a bitch.”

“There’s no other way?” I asked.

“Trust me, we’ve been doing this for a long time.”

I thought about running and immediately saw myself thinking about it. I wondered how many times I had died running.

“Don’t worry; it’ll be quick. No worse than coldtime, really. And this time you don’t even have to wake up.” I said. I watched myself caress the matte casing of the weapon in my hand, while another part of me reached out to grasp Melano’s open palm. Squeezed it tight.

“But before we tuck you in for the night,” Melano’s double added, “there is just one thing you can do for us—for old times’ sake. Just out of curiosity: what did you call this planet?”

I realised I could lie. Or I could refuse to tell. I wondered what the probabilities were for that too, and saw myself wonder.

“It’s alright, I can hardly blame you,” my other said. “I can already see it anyway. Have you got it yet, Melano?” she addressed her partner.

Melano squinted.

“Yes,” she decided, at length. “Hah, a rarity, that. Let’s see, that brings Hancock up to … 2.8%, is it?”

“I think you’re right,” my double replied, cold eyes staring straight back at me. “We chose Schwarzenegger, for what it’s worth. Currently running at over 19% with good odds on overall favourite.”

I levelled the gun at myself. Melano’s double did the same for her. Smiled.

“I wish I could say it was nothing personal, but …”

Thought jolted.

Craig Thomson is an artist, carpenter, musician and sometime writer of stories from Fife. He graduated from Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design in 2012 and now lives and works in Glasgow.

What Goes Up

Stuart Beel

SF Caledonia

SF Caledonia

Monica Burns

George MacDonald’s Phantastes (1858) is a long, meandering, twinkling dream. When I reached the end and closed the covers I found myself blinking as if I’d just woken up. It took a while to find my way back down to reality.

It reminded me of so many things. The whole way through, the music I had playing in my head was Hozier’s In the Woods Somewhere. I was reminded of Tim Burton, Phillip Pullman, Lewis Carroll, Grimms’ Fairy Tales, C.S. Lewis, medieval allegorical romances such as The Romance of the Rose and a coffee-table art book called Good Faeries/Bad Faeries by Brian Froud.

The fairy-story tradition is a very familiar one to modern audiences, and the paths through Fairyland are well trod, but George MacDonald is recognised as one of the fathers the modern fantasy genre. George MacDonald was a huge influence on both C.S. Lewis (Chronicles of Narnia author and famous friend of J.R.R. Tolkein), and Lewis Carroll (Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland). Carroll was a personal friend of MacDonald and was encouraged to submit Alice in Wonderland for publication because of the eager reception of MacDonald and his children. C.S. Lewis was sixteen when he first read Phantastes. He would later say MacDonald’s work changed his outlook on life and had a major impact on his own writing.

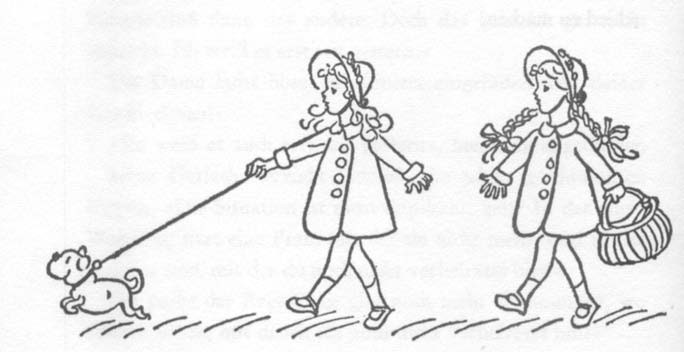

At its heart, Phantastes, subtitled, A Faerie Romance for Men and Women, is a wander around a richly imagined Fairyland. The protagonist is Anodos, whose name can be appropriately translated from the Greek as ‘pathless’. He has just turned 21 when he discovers a tiny fairy who tells him he is of fairy blood, and will be able to access Fairyland. That very night, Anodos’ bedroom transforms. His sink overflows and turns into a stream, and the carpet that was flower patterned, turns into a field of actual daisies. Anodos realises that this is the gateway to Fairyland, and like all romance heroes before him, he wanders deep into the mystical realm that unfolds before his eyes, encountering all kinds of people and creatures, existing either to help or hurt him on his path towards self-discovery.

At its heart, Phantastes, subtitled, A Faerie Romance for Men and Women, is a wander around a richly imagined Fairyland. The protagonist is Anodos, whose name can be appropriately translated from the Greek as ‘pathless’. He has just turned 21 when he discovers a tiny fairy who tells him he is of fairy blood, and will be able to access Fairyland. That very night, Anodos’ bedroom transforms. His sink overflows and turns into a stream, and the carpet that was flower patterned, turns into a field of actual daisies. Anodos realises that this is the gateway to Fairyland, and like all romance heroes before him, he wanders deep into the mystical realm that unfolds before his eyes, encountering all kinds of people and creatures, existing either to help or hurt him on his path towards self-discovery.

To best appreciate Phantastes, you should be prepared to not only immerse yourself in MacDonald’s Fairyland, but into the mindset of his contemporary readers. In style and language, it is very Victorian. Often flowery and melodramatic, unbelievable and peppered with some bad poetry, it can be a bit of a slog by modern standards. But if you forgive it for its pomp, it’s a lot more enjoyable. The Victorians were enamoured with the medieval era. Scottish author, Walter Scott, was largely responsible for this resurrection and romanticising of notions of chivalry and courtly love, Arthurian legend, knights and damsels and mythical creatures and magical lands. A lot of faux-medieval tales such as The Lady of Shalott, bloomed in this period, and in art, there were the Pre-Raphaelite painters who loved to use tragic females like Ophelia as their Muse. One of the Pre-Raphaelites, Arthur Hughes, illustrated the 1905 edition of Phantastes, so the dreamy, elegant world of that style of art and the Fairyland of George MacDonald are very much connected.

One cause for potential frustration among readers is the protagonist. Anodos is characterless enough to be a vessel into which you can pour your own personality. He’s often arrogant or brazen enough to undertake things that a properly fleshed out character may refrain from doing. Don’t open that door, Anodos is told, touch not these statues, do not trust the Lady of the Alder Tree—so what do you think he does? It’s not a bad thing—if he obeyed the rules he would remain in the cushy confines of his comfort zone, and so would the reader. For a story to be entertaining, the protagonist has to be a bit of an idiot. As he takes us through Fairyland, we want him to make as many missteps as steps so that we can see the fully-rounded wonderland, all its beauty and all its goblins. The only things that truly make a lasting impression on Anodos’ character are love and the strange shadow that dogs him for a lot of his journey.

This shadow is an interesting thing to analyse. At first, I took it to mean depression, or any kind of black emotional state that can cloud one’s judgement and ability to see things clearly. As it turns out, the shadow is Doubt, and stops Anodos seeing the magic of Fairyland and all its beauty and wonder. It follows him like a curse throughout the book, and his thoughts about it and what it does to him can often be poignant.

Anodos falls in love with a woman who is literally an object, and his love is based entirely on her beauty. For a modern reader this is a tad annoying. However, for the Victorians versed in the spirit of medieval revival, the tradition of courtly love was all about the unattainable lady. Ladies were worshipped from afar, idealised to the point that their depictions bordered on otherworldly, and those that loved them raised them high on pedestals (a notion that is literalised in a section of the book where Anodos serenades his lady into existence onto the top of an actual pedestal). Beauty and grace were worshipped and lovers were inspired to better themselves, emotionally, spiritually, and physically in order to attain their lady.

Everything Anodos goes through is to help him grow, so many people take Phantastes to be an allegory for growing up, meaning that Fairyland is the adult world, and the protagonist, at 21 is just new to it and exploring all its beauty and all its nightmares. Although MacDonald was a minister and preacher, Phantastes isn’t a religious allegory—in fact with Anodos’ behaviour in mind, you could argue that the book advocates exercising free will and disobedience as the route to personal growth rather than faith.

To read Phantastes as science fiction, you have to dig deeper. Undeniably, it fits into the fantasy genre, but science seems virtually absent from it on first glance. However, prolific Scottish literature critic Cairns Craig, makes a claim for its inclusion in the SF canon, saying that the book reflects knowledge of the energy science theories of James Clerk Maxwell (another Scot, and Professor at Aberdeen University after MacDonald left) which were the most innovative theories in energy physics since Newton. Craig points to the passage in Phantastes where the solid physical matter of Anodos’ sink and carpet dissolve into water and grass as an example of MacDonald imaginatively exploring the possibilities of Maxwell’s theories of shifting, eternal energies able to transform into other things. In the fantasy genre, strange occurrences like this can be explained by magic, whereas in science fiction, the same things can be explained through science. Phantastes, though still rooted in the magical, dabbles in this kind of scientific thought, although the ultimate explanations are magical. The book is a strange mixture of both fantasy and science fiction in this regard.

Also, if we consider the two basic functions of modern science fiction—to imagine a future or a different world out of what if possibilities, and secondly, to hold up a mirror to our own world through the means of creating another—we see that science fiction and fantasy both have this in common.

Another interesting extract within Phantastes that has the potential to lean into science fiction, is the embedded narrative of a Czech university student who falls in love with a woman who lives inside a magic mirror. She inhabits the world inside the mirror and interacts with the objects in the room’s reflection, but does not appear physically in student’s room. Reading it as a fantasy story, it’s a magical curse, but I have previously read SF stories where instead of a mirror it’s a monitor or a screen, and instead of magic, it’s a blip in spacetime, resulting in an overlap of parallel universes. MacDonald would not have had these kinds of ideas in mind in 1858, but his imagination and curiosity for fantastic and scientific possibilities would have made him a very good SF writer if he was around today. Certainly, the imagination and fascination with other worlds seems to run in his family—his grandson, Philip MacDonald, who wrote many books in the 1930s-60s under different pen-names, including W.J. Stuart—wrote ‘the book of the film’ for Forbidden Planet.

Another surprising revelation, for me at least, was this: when I was doing my research for this piece, scanning along the library shelf, I was shocked to read the title of another of George MacDonald’s books—The Princess and the Goblin. The adventures of Curdie and Princess Irene, in the cartoon adaptation, was one of my favourite films as a child, and I’m sure I’m not alone. In childhood, of course, you never consider the authors, and I never questioned that a cartoon even had one. I never would have dreamed that it was written in the 1850s by a man from my town, and alumni of the University of Aberdeen, who, about 150 years ago, walked the same streets I do every day.

It could be said that his roots were romantically Celtic—a background Walter Scott would have loved: he was a direct descendant of the Highland clan, the MacDonalds of Glencoe. His ancestors escaped the infamous Massacre of Glencoe, and others fought alongside the Jacobites in the Battle of Culloden in 1745. George MacDonald himself was born into a respected farming family in 1824 near Huntly, north Aberdeenshire. At university, he was known to be a well-liked, handsome, intellectual and morally upright man who loved romance literature and daydreaming and kept company with poets and philosophers. He turned to religion after university, apparently a natural preacher, and became a Minister at a Congregational Church in Arundel, Sussex in England. He married and had children there, and it was around this time he began to write seriously. His first publication in 1855 was a dramatic play-poem called Within and Without. When his unorthodox views upset his conservative congregation in Arundel, he was forced to resign. He relocated to Manchester where he made his career preaching and lecturing. His first prose book was Phantastes, but he didn’t become an established success until his following book, David Elginbrod, a story of peasant life in Aberdeenshire, a lot of it written in Aberdonian Doric. From there, he went on to become an eminent, well-known writer and preacher living in London. In addition to influencing Carroll and Lewis, he also had a huge impact on Charles Kingsley who wrote The Water Babies. He was also acquainted with (and apparently photographed alongside) Alfred Lord Tennyson, Charles Dickens, William Makepeace Thackery and Wilkie Collins, to name but a few. Mark Twain came to see him in England and over in America, he was friends with Walt Whitman. MacDonald enjoyed a long career and a long life, writing many works of fantasy, non-fiction and poetry, before passing away in 1905.

Phantastes is an enchanting book, best enjoyed while relaxing in the shade beneath a gently whispering tree. To ponder over it is like analysing a dream, but I’d recommend reading it in shorter sittings. It has so many beautiful moments, but one of my favourite things to take away from has to be this very simply-put proverb: ‘Past tears are present strength’. With its high-flown Victorian style, it may not be the book everyone dives to read nowadays, but the world of fantasy and science fiction literature has a lot to thank it for.