“Naturally! But why does he sit apart as if he disdained everyone at Quanorq?”

“Everyone?” mused the Lady Shaunica as if to herself.

The Lady Dualtimetta moved away. “My dear, excuse me; now I must hurry; I have an important part in the pageant.” She went her way.

The Lady Shaunica hesitated, then, smiling as if at some private amusement, went slowly to the alcove. “Sir, may I join you here in the shadows?”

Rhialto rose to his feet. “Lady Shaunica, you are well aware that you may join me wherever you wish.”

“Thank you.” She seated herself on the couch and Rhialto resumed his own place. Still smiling her secret half-smile she asked: “Do you wonder why I come to sit with you?”

“The question had not occurred to me.” Rhialto considered a moment. “I might guess that you intend to meet a friend in the foyer, and here is a convenient place to wait.”

“That is a genteel reply,” said the Lady Shaunica. “In sheer truth, I wonder why a person such as yourself sits aloof in the shadows. Have you been dazed by tragic news? Are you disdainful of all others at Quanorq, and their pitiful attempts to put forward an appealing image?”

Rhialto smiled his own wry half-smile. “I have suffered no tragic shocks. As for the appealing image of the Lady Shaunica, it is enhanced by a luminous intelligence of equal charm.”

“Then you have arranged a rendezvous of your own?”

“None whatever.”

“Still, you sit alone and speak to no one.”

“My motives are complex. What of yours? You sit here in the shadows as well.”

The Lady Shaunica laughed. “I ride like a feather on wafts of caprice. Perhaps I am piqued by your restraint, or distance, or indifference, or whatever it may be. Every other gallant has dropped upon me like a vulture on a corpse.” She turned him a sidelong glance. “Your conduct therefore becomes provocative, and now you have the truth.”

Rhialto was silent a moment, then said: “There are many exchanges to be made between us — if our acquaintance is to persist.”

The Lady Shaunica made a flippant gesture. “I have no strong objections.”

Rhialto looked across the foyer. “I might then suggest that we discover a place where we can converse with greater privacy. We sit here like birds on a fence.”

“A solution is at hand,” said the Lady Shaunica. “The duke has allowed me a suite of apartments for the duration of my visit. I will order in a collation and a bottle or two of Maynesse, and we will continue our talk in dignity and seclusion.”

“The proposal is flawless,” said Rhialto. He rose and, taking the Lady Shaunica’s hands, drew her to her feet. “Do I still seem as if dazed by tragic news?”

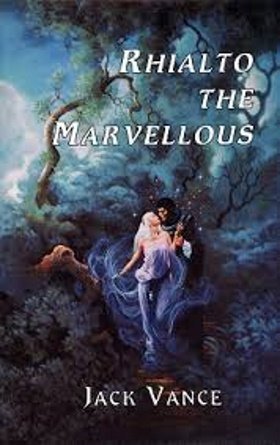

“No, but let me ask you this: why are you known as ‘Rhialto the Marvellous’?”

“It seems to be an old joke,” said Rhialto. “I have never been able to trace the source.”

As the two walked arm in arm along the main gallery they passed Ildefonse and Byzant standing disconsolately under a marble statue. Rhialto accorded them a polite nod, and made a secret sign of more complicated significance, to the effect that they might feel free to return home without him.

The Lady Shaunica, pressing close to his side, giggled. “What a pair of unlikely comrades! The first a roisterer with mustaches a foot long, the second a poet with the eyes of a sick lizard. Do you know them?”

“Only slightly. In any case it is you who interests me and all your warm sensitivities which to my delight you are allowing me to share.”

The Lady Shaunica pressed even more closely against him. “I begin to suspect the source of your soubriquet.”

Ildefonse and Byzant, biting their lips in vexation, returned to the foyer, where Ildefonse finally made the acquaintance of a portly matron wearing a lace cap and smelling strongly of musk. She took Ildefonse off to the ball-room, where they danced three galops, a triple-polka and a kind of a strutting cake-walk where Ildefonse, in order to dance correctly, was obliged to raise one leg high in the air, jerk his elbows, throw back his head, then repeat the evolution with all briskness, using the other leg.

As for Byzant, Duke Tambasco introduced him to a tall poetess with coarse yellow hair worn in loose lank strands. Thinking to recognize a temperament similar to her own, she took him into the garden where, behind a clump of hydrangeas, she recited an ode of twenty-nine stanzas.

Eventually both Ildefonse and Byzant won free, but now the night was waning and the ball was at an end. In sour spirits they returned to their domiciles, and each, through some illogical transfer of emotion, blamed Rhialto for his lack of success.

2

Rhialto at last became impatient with the plague of ill feeling directed his way for no very clear reason, and kept to himself at Falu.

After a period, solitude began to pall. Rhialto summoned his major-domo. “Frole, I will be absent from Falu for a time, and you will be left in charge. Here —” he handed Frole a paper “— is a list of instructions. See that you follow them in precise detail. Upon my return I wish to find everything in exact and meticulous order. I specifically forbid that you entertain parties of guests or relatives on, in or near the premises. Also, I warn that if you meddle with the objects in the work-rooms, you do so at risk of your life, or worse. Am I clear?”

“Absolutely and in all respects,” said Frole. “How long will you be gone, and how many persons constitute a party?”

“To the first question: an indefinite period. To the second, I will only rephrase my instruction: entertain no persons whatever at Falu during my absence. I expect to find meticulous order upon my return. You may now be off about your duties. I will leave in due course.”

Rhialto took himself to the Sousanese Coast, in the remote far corner of South Almery, where the air was mild and the vegetation grew in a profusion of muted colors, and in the case of certain forest trees, to prodigious heights. The local folk, a small pale people with dark hair and long still eyes, used the word ‘Sxyzyskzyiks’ — “The Civilized People” — to describe themselves, and in fact took the sense of the word seriously. Their culture comprised a staggering set of precepts, the mastery of which served as an index to status, so that ambitious persons spent vast energies learning finger-gestures, ear-decoration, the proper knots by which one tied his turban, his sash, his shoe-ribbons; the manner in which one tied the same knots for one’s grandfather; the proper and distinctive placement of pickles on plates of winkles, snails, chestnut stew, fried meats and other foods; the curses specifically appropriate after stepping on a thorn, meeting a ghost, falling from a low ladder, falling from a tree, or any of a hundred other circumstances.

Rhialto took lodging at a tranquil hostelry, and was housed in a pair of airy rooms built on stilts out over the sea. The chairs, bed, table and chest were constructed of varnished black camphor-wood; the floor was muffled from the wash of the sea among the stilts by a rug of pale green matting. Rhialto took meals of ten courses in an arbor beside the water, illuminated at night by the glow of candle-wood sticks.

Slow days passed, ending in sunsets of tragic glory; at night the few stars still extant reflected from the surface of the sea, and the music of curve-necked lutes could be heard from up and down the beach. Rhialto’s tensions eased and the exasperations of the Scaum Valley seemed far away. Dressed native-style in a white kirtle, sandals and a loose turban with dangling tassels, Rhialto strolled the beaches, looked through the village bazaars for rare sea-shells, sat under the arbor drinking fruit toddy, watching the slender maidens pass by.

One day at idle whim Rhialto built a sand-castle on the beach. In order to amaze the local children he first made it proof against the assaults of wind and wave, then gave the structure a population of minuscules, accoutered as Zahariots of the Fourteenth Aeon. Each day a force of knights and soldiers marched out to drill upon the beach, then for a period engaged in mock-combat amid shrill yells and cries. Foraging parties hunted crab, gathered sea-grapes and mussels from the rocks, and meanwhile the children watched in delighted wonder.

One day a band of young hooligans came down the beach with terriers, which they set upon the castle troops.

Rhialto, watching from a distance, worked a charm and up from a court-yard flew a squadron of elite warriors mounted on humming-birds. They projected volley after volley of fire-darts to send the curs howling down the beach. The warriors then wheeled back upon the youths who, with buttocks aflame, were likewise persuaded to retreat.

When the cringing group returned somewhat later with persons of authority, they found only a wind-blown heap of sand and Rhialto lounging somnolently in the shade of the nearby arbor.