The final blow came at two in the morning on September 15. A crowd of 4,000 had gathered at Lexington and 52nd to watch Marilyn Monroe’s skirt blow up. The vanilla halter, electric fans, flashing cameras, and screaming men made for a frenzied publicity stunt, and an explosive scene between Marilyn and Joe. With each whoosh of the subway DiMaggio’s blood boiled hotter. Smirky gossip hound Walter Winchell poked him in the ribs and said, “What’re you gonna do about it, Joe?” Fuming, Joe stormed off to get drunk at Toots Shor’s. He caught the earliest flight to San Francisco, and Marilyn returned to LA alone.

Distraught, she sought advice from “Old Jane” Russell. Must she give up her own identity in marriage? How did she manage an acting career along with a husband and children? Jane advised her to leave studio worries at work and concentrate on Joe when she was at home. But Marilyn couldn’t switch off like that nor would she want to. Even if she did, she would have had to numb out with Nembutals and Sinatra records to clear her head. Marilyn was beginning to see irreconcilable differences—not just between herself and Joe but between family and career.

Some actresses mean it when they say they want to focus on family, that all they want to do now is cook, nurse babies, and change nappies. Marilyn didn’t. She meant that she was deeply invested in her relationship, and that she wanted to make her husband happy. For Joe—and for most mid-century American men—that wasn’t enough. As one studio insider predicted, “If it’s ever a question with Marilyn of marriage or career, the marriage may go.”

The marriage did go. On October 22, 1954, dressed in a LeMaire suit of black gabardine and a strand of Mikimoto pearls from Emperor Hirohito, a puffy-eyed Marilyn stood on the steps of Santa Monica Municipal Court and announced her split from the Yankee Clipper.

* * *

Marilyn’s career had already been teetering, and now divorce flung her into the media hailstorm. Dogged by photographers, hounded by journalists, and emotionally shattered by the breakup of the century, Marilyn needed another champion.

Days after the breakup, Marilyn got a phone call from Milton Greene. He was back in town with Amy; would she meet them at a party at Gene Kelly’s? Marilyn paused. The last thing she needed was another trade party, all the puffed-up banter and inside gibes. Charades was an institution at Gene’s, and the very thought paralyzed her. Sensing her hesitations, Milton offered a solution: He’d take her to dinner first, then they’d slink into the party late and undetected. (He’d never got the hang of charades, either—the game was too literal for them both.)

Charades was in full swing by the time they arrived. Amy waved Marilyn over and greeted her warmly. Makeup-free, camel coat thrown over a black Capezio leotard, hair still wet from her bath, Marilyn was hardly the siren Amy had expected: “I’ve never seen anyone so bedraggled. She looked like a wet chicken.”

Marilyn shrank into a corner with Milton. After nearly a year apart, they clicked right back into high gear, heads bent together in catlike conspiracy. This bright-kerchiefed boy and shy little chicken were planning something big.

* * *

With her professional and personal life in upheaval, Marilyn needed a plan. She’d been battling Fox for more than a year and still didn’t have the one thing she wanted: creative control. Even a powerhouse such as Feldman couldn’t deliver her that. He managed to squeeze more money from Fox, but failed to grasp Marilyn’s ultimate goal. Milton understood the importance of script, director, and cinematographer approval. Why not strike out on her own, he suggested, move to New York and start her own production company? It was a concept they’d been bouncing around for months. Now those vague conversations took a serious turn. Within days, Marilyn moved into the Voltaire Apartments on Sunset Boulevard, where she and Milton smoked and snacked and schemed about their secret coup. “The idea was to create an independent production company for Marilyn so that she could break out of her typecasting and make films that she wanted to make,” recalled Amy, who was part of the plan from the start. “She loved it. She preened. She said, ‘I’m gonna be the head?!’”

From the very beginning, part of the appeal was New York itself. “Los Angeles is without the cultural and intellectual ferment which is to be found in any other large city in the world,” wrote Marilyn’s friend Maurice Zolotow, who hated LA as much as she did and claimed that the city’s major cultural achievements were “the square-block supermarket, the one level and multi-level ranch house, the backyard barbeque, laundromats, and drive-in hamburger joints.” (Marilyn did like the drive-in hamburger joints.) LA’s chlorinated grottoes and fake Florentine fountains were all she knew.

So far, her trips to New York had been disappointingly flat: overnight rides on the 20th Century Limited, huddled in her bunk reading Swann’s Way while she was supposed to be learning the script for Love Happy. Toothbrush, powders, and lipsticks crammed into her cheap plastic travel case, blouses and bras stuffed in the trunk of white rawhide she’d bought on credit to look luxe and city-chic. For years she’d glimpsed Manhattan in frustrating little fragments. Now it was about to become her home.

Milton sprang into action immediately. “The plan was to speak to the lawyers,” he explained decades later, “find out what was what, create a new deal and fight Fox.” He mailed Marilyn’s contract to his lawyer, Frank Delaney, who denounced it as a “slave labor agreement.” Even better, Delaney spotted a few loopholes that might give them an out. Milton was thrilled, but Marilyn still fretted over possible consequences. “Eventually, they’re gonna give in,” he assured her. “That’s how it works.”

Within days, Marilyn’s Hollywood team was replaced by a crew of New Yorkers. Frank Delaney signed on as her lawyer. Superagent Charlie Feldman was jettisoned in favor of Milton’s friend Jay Kanter. As for housing, she would stay with the Greenes in their Connecticut country home, beyond the reach of Zanuck’s henchmen. Milton would take care of everything; she could leave all the business dealings to him. Milton’s lack of experience didn’t seem to bother her. He had boundless enthusiasm, impeccable taste, and a quiet, street-smart confidence in his creativity and wit. “She was lost and alone,” he said. “Who’s she gonna trust—not Zanuck, not Charlie Feldman, not DiMaggio. She had no one she could trust except me. Because I’m gonna give her a straight answer. I’m not gonna fuck around.” He believed in Marilyn: “She wasn’t dumb—she was intelligent, and she had a good head. I always thought she was quick. There were times when something was way over my head, I just couldn’t believe it, and she’d come up with a suggestion or make a remark about something and I thought, ‘Well shit, why didn’t I think of that?’”

In late November Milton resigned from his position at Look and committed to Marilyn exclusively. Both had faith in their art, and were ready to risk it all to realize their vision. “All any of us have,” Marilyn reflected months later, “is what we carry with us, the satisfaction we get from doing what we’re doing and the way we’re doing it.” She trusted Milton and his talents entirely. “I didn’t have much experience,” Milton admitted later, “but if I had to do it all over again, I don’t think I could do better.”

* * *

By December the whole town was buzzing with rumors of these enfants terribles and their haphazard plan. Friends called frantically, desperate to talk some sense into Marilyn, begging her not to risk her future on an inexperienced kid. How could she be so impulsive, so reckless? But Marilyn didn’t leave impulsively. Her LA friends didn’t realize she’d been planning her escape for years.

In her personal life she flitted about capriciously—she was notoriously myopic in matters of the heart. But when it came to her career—the thing that mattered most—Marilyn never lost sight of the larger picture. Pink Tights and There’s No Business Like Show Business weren’t the first jobs that bored her. Instead of diva tantrums and tears, she rebelled on the stealth, stashing Lincoln Steffens’ books in her red Gucci bag, hidden under peanut brittle and plastic curlers. She quietly made choices that advanced and empowered her, such as firing her drama coach and signing on with Michael Chekhov. He affirmed what she had always intuitively sensed—the value of looking inward. Rather than battle her “weaknesses,” Chekhov showed her how to work with her gifts. Under his guidance, Marilyn channeled her own intelligence rather than acting like a trained monkey. “You can do anything,” Chekhov told her. “Don’t let them trap you into what they want.”

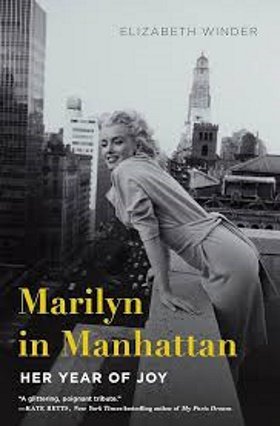

As much as she wanted to bolt, Marilyn was savvy enough to wait for her moment. The Seven Year Itch wrapped that fall, and she sensed it was going to be big. This would be the fourteenth film she’d cranked out for Fox, and if she had it her way, the last.

Zanuck and his cronies were oblivious. For years Marilyn had been playing the ditz, churning out money, all the while burning her dumb blonde effigy in secret.

* * *

Knowing she’d be free from the pressures of Hollywood, Marilyn relaxed into her final weeks in LA. An atmosphere of unusual warmth and merriment lit up the city. Sammy Davis Jr. was back at Ciro’s after the car wreck that nearly blinded him, and everyone was out toasting him at the Mocambo and the Crescendo, wearing jeweled eye patches in support, brandishing highballs like pirates. For the first time in years, Marilyn let loose, carousing the clubs with Sammy D. and his crew. You’d find her draped on a striped banquette feeding petits fours to Tony Curtis, or on the floor with Milton petting someone’s bichon frise, a rhinestone barrette clipped to its fur. At parties they hung on each other like two teenage beatniks—Milton in Roman black and Marilyn in those dark slip dresses she wore all the time. “The two of them were just giggly,” a friend remembers. “It was almost like a sister and brother between them. I don’t know if there was a romance there.”

On her last day in LA, Marilyn threw open two Louis Vuitton trunks and gathered the scraps of her life that still mattered to her: a framed picture of Abraham Lincoln, a triptych of Eleonora Duse, a Vassarette bra, The Sonnets of Edna St. Vincent Millay. Dirt to diamonds, LA was all Marilyn had ever known, dating from the orphanage that looked out over RKO. From her window she could see Mount Lee, with HOLLYWOOD spelled in those boxy wooden letters. Her bleached-out childhood was California through and through—all smudge pots and shantytowns, shacks of tin clapboard and chain-linked yards littered with crosses of white plastic. Backyard preachers kicked up fire and brimstone under sad little orange groves. They terrified her—the doomsayers and soothsayers with their larders full of wheatgrass, their aversion to Tylenol and long conversations about God and what it really meant to eat grapes as a Christian Scientist.

Still, there was something raw and lovely about Los Angeles—the lights twinkling over Catalina Island, West Hollywood’s scent of overripe flower pulp, amphetamine, and exhaust fuel. Departures crash into you with spiky intensity, throwing daily mundanities into high relief. Suddenly the ding of an elevator, the glint of a teaspoon on a room service tray, or the last snack you buy at your favorite bodega moves you to tears and you’re flung into nostalgia for a place you haven’t left yet and didn’t even think you could miss.

What was she thinking on that last day, when she snapped shut her trunks, hailed a taxi, and rode down Sunset Strip for the last time? There was the Villa Nova, all stained glass windows and hacienda wood beams, where she’d met Joe DiMaggio for their first date. There was the Polo Lounge, where you could order a palm reading along with your Tom Collins, and the Garden of Allah, where she’d languished waiting for Joe Schenck or Sydney Chaplin to buy her a drink. And of course, there was Schwab’s, where she’d suck down pills and iced coffee with Sidney Skolsky, gawking at “the real beautiful call girls,” the air thick with nicotine, watered-down ice cream, and perfume.

“It must have taken great courage to quit Hollywood as you did, to give up all the luxury, the money, the importance—after being so very poor,” said Elsa Maxwell, who spoke to her months later.

“No,” she said softly. “No, Elsa, it didn’t take any courage at all. To have stayed took more courage than I had.”

Two

The Fugitive

“Recently somebody asked me, ‘What are you trying to do in New York? What do you honestly want to be?’ I told them, ‘I want to be an artist.’”

MARILYN MONROE

The Greenes lived in a hilltop country house in the idyllic town of Weston, Connecticut. The house had been built around an eighteenth-century stable, with towering ceilings and airy walls and a massive log fireplace flanked by custom-made sofas. Milton had remodeled it, putting French glass where the barn doors had been, adding on darkrooms and studios with culkwood floors. There were sixteen rooms, including a plant-filled conservatory connected to a huge Colonial kitchen rigged with modern appliances. The guest room had been revamped and freshly painted just for Marilyn. “We did the guest room over for her,” Amy Greene told Photoplay. “It’s in purple, pink and white. The curtains and dust ruffles are crisp white organdy. The wallpaper is lavender with a small purple figure and the rug just matches the purple. There’s a pink quilted bedspread and dark purple velvet throw pillows. The chest is an old one with a white marble top and I put pink china lamps on it. It’s a simple and sort of old fashioned room, but it is as dainty as she is and suits her exactly. Marilyn loves it.”

Eleven acres. Vegetable gardens. Stretches of wild woodland like something out of a fairy tale or the old Russian books she loved. In lower Connecticut, forty miles from New York, this was as close to nature as she’d ever been. She took daily walks in the woods, bundling up in Milton’s coats and stomping through the snow with the terriers like a little Grushenka or Lara. Her first snow—she loved the sounds of the snow crunching under her boots. She’d never seen a tree without leaves—or even changing seasons. “I remember one day we were driving home from a friend’s house,” Amy remarked. “Marilyn looked up at the hillside and remarked that the trees were just dead, bare sticks. Then, the next week, they began to turn green. To her, it seemed like a miracle.”

That magical winter when her focus turned inward, Marilyn woke up when she wanted to, wandering from her bed to a balcony that overlooked birchwoods and mountains. She lived in her white bathrobe and spent hours soaking in bubble baths—soapy blonde hair piled on her head, skin pink and rosy as a Boucher cherub. “You look like a strawberry soda,” Amy observed to Marilyn’s delight.

Surprisingly, Marilyn adjusted immediately to the rhythms of family life. Amy—half-expecting prima donna antics—was delighted with her houseguest: “She made her own bed, kept her room tidy, brought down her clothes on wash day. If she slept late, she would make her own breakfast, rinse off the dishes and put them in the dishwasher. Neither our maid nor I had to wait on her.”

The Greenes’ cook, Kitty Owens, liked Marilyn immediately, detecting no diva or starlet tendencies. Each evening she’d pop into the kitchen ready to peel potatoes or snap string beans (“Is this the right size?”). They’d chat about men, and Marilyn confessed her crush on Abraham Lincoln. “He was such a great guy,” she’d sigh as if he’d taken her on a date to the Clambake Club. “When I see a man like that, I would love to just sit on his lap.”

With no immediate projects, Marilyn could enjoy Kitty’s home cooking without worrying about gaining half an ounce. After years of raw egg concoctions and lone liver chops broiled in hotel kitchenettes, Marilyn ate with relish. She preferred savory to sweet and loved vegetables—stewed tomatoes, stewed corn, string beans, red cabbage with apples, and winter squash. On cold nights she’d warm up with hot bowls of chili or her favorite late-night snack—eggs scrambled with anchovies and capers. Kitty kept plenty of spinach on hand for Marilyn’s iron-rich diet. Once she found her tiptoe on the counter scraping spinach off the ceiling (“Kitty, I had a little accident.…”). She’d opened the pressure cooker too soon.

The Greene household took Marilyn’s bizarre habits in stride. Each morning Kitty’s husband Clyde would haul a bag of ice upstairs and pour it in a basin. Marilyn would stand on it: “It will make my legs firm!”