Milton worried that she’d get restless, so he took her for long drives on his German motorcycle or sometimes drove her into Manhattan for ritzy nights on the town. She even saw Joe again. “I remember the first time the telephone rang in Connecticut and it was DiMaggio inviting us to dinner that night,” remembered Amy. “I went gaga. We went to the old El Morocco. I sat there and talked baseball with Joe and he was ecstatic. Marilyn never had any interest in all that. He held my hand in his—it was like putting your hand in a giant muff. It was a wonderful evening.”

For the most part, Marilyn was quite happy to stay at home. Trimming the Christmas tree, roasting carrots with Kitty, morning jogs with Amy—these rituals were new to her and delightful. She adored the Greenes’ baby, Joshua, always offering to feed him or give him his nightly bath, wrap him in one of her terrycloth robes, and surround him with a nest of pillows. She lavished him with gifts including a pajama bag called Ethel and a huge stuffed teddy bear named Socko. “If the rest of us are busy,” Amy Greene told Photoplay, “she’s always down on the floor playing with him.” For the first time Marilyn had stability—and more important, time.

Meanwhile, the press still reeled from her shattered marriage. Headlines such as I’LL ALWAYS BE ALONE and DON’T BLAME YOURSELF, MARILYN popped up, including an open letter to the newly divorced actress. Threatened by her choices, they turned the tables and hinted of “a nameless fear that has ruled her all her life.” The exploding popularity of psychoanalysis led to trendy diagnoses and renewed interest in Marilyn’s troubled past. The stain of divorce had knocked back their goddess to her dirty roots. Suddenly Marilyn was back to being an orphan—one with “no real worth of her own,” a “frightened, lonely, and thoroughly insecure young woman.” They riffed on tired clichés—poor little glamour girl, alone for the holidays.

While the press spun hackneyed tales of a cheerless Christmas season, Marilyn met a new set of creative personalities. The Greenes kept open house on the weekends, filling their rooms with Josh and Nedda Logan, Mike Todd, literary agent Audrey Wood, Leonard Bernstein, and Richard Rodgers. Initially Marilyn shrank from it all, the piano sing-alongs and theater gossip. She’d hide for hours in the bath before padding downstairs in slacks and a sweater, curling into a chair with a vague smile on her bare face. Sometimes she’d linger on the lower stairwell, swinging her legs over the slate blue carpet, baby Josh holding a tumbler of bourbon to her mouth. Some nights she wouldn’t emerge at all: “Do you mind if I don’t come out tonight?” she’d whisper to Amy through the bathroom door.

“At a party she never sat in a corner playing regal and expecting guests to come to her,” wrote Amy Greene. “More likely, I’d find her emptying ash trays or picking up glasses. A lot of people in show business and advertising and publishing live up here and she was just one of us. And she knows how to listen, that girl. To women as well as to men. It didn’t take the girls long to see that Marilyn wasn’t after anyone’s husband. She just simply fit into our crowd and everyone loved her.”

Amy was quick to dismiss the sly jabs at Marilyn’s temptress reputation: “They must have thought Marilyn was a combination of Theda Bara and Mata Hari—the vamp and the threat. Many times people would say to me, ‘Oh, how can you have her in your house, in your life, blah?’ I trusted her completely. As a woman, I trusted her. I was secure in my marriage and I was secure with her.”

Watching America’s favorite pin-up queen lounge around her house in a robe triggered no insecurity in Amy: “It was the other way around—I intimidated her. She said to me once, ‘You intimidate me.’ I said that’s good—everyone should be afraid of somebody.” She had yet to realize that Marilyn was afraid of everyone.

Many feel the opposite when they say “I’m a very secure person,” but Amy was telling the truth. At twenty-five, she was already startlingly confident, with the crisp tone and assured mannerisms of someone much older. It helped that Amy was just as gorgeous, albeit in a sleeker, darker way. She was five feet and ninety-five pounds with a pert little nose and a dusting of tawny freckles that made her look about fifteen. She barely wore any makeup—Marilyn had to teach her how to apply eyeliner. What’s more, Amy inhabited the rarefied world Marilyn could only dream of. She’d grown up on the Upper West Side; she’d posed for Richard Avedon; she’d been to convent school; she knew Anne Klein and fit into sample sizes; and she’d been suckled by a Cuban witch as a baby.

“You’re so lucky to have a man like Milton love you and marry you,” Marilyn remarked with a wistful little look. “I know,” Amy shot back, “but he’s also lucky to have me.” Marilyn giggled. She’d never heard a woman say that before.

With Milton working in the city, Marilyn and Amy spent afternoons antiquing or driving to Westport for coffee and eclairs at the Daily Corner, a café owned by Milton’s sister Heny. “She liked to drive,” Amy recalled. “We’d take the convertible and go sailing along the highway with the top down. We both liked to feel the wind on our faces and the warmth of the heater on our legs.”

Amy wasn’t just “putting up” with Marilyn—she liked her. “We’d discuss everything from clothes to housekeeping to babies to headlines. Sometimes we’d giggle like a couple of school kids. Others, we’d come up with some sure-fire formula for saving the world. You know the way women do.… I thought it was just great that she could come to visit us. It would be nice to have a girl around the house. I grew up in boarding schools, and although we have lots of friends, there’s just so much distance and we’re all so busy that I don’t get much chance to sit down to talk with other women.” The feeling was mutual. Marilyn had few close girlfriends in the Hollywood years—it was all backbiting starlets in the Beverly Hills Hotel.

In her starch-white collars and convent-chic ponytails, Amy was the type of woman inevitably described as “together” or “polished”—quite the opposite of Marilyn’s slippery straps and misplaced bras. But she admired Amy’s self-possession and even acquired some of it during her winter sabbatical. “She was so impressed with anyone who is efficient,” wrote Jane Russell, another friend who managed to balance glamour with practicality. Well-meaning friends would give Marilyn address books and desk calendars, but she’d use them as journals and scrap paper, jotting down little poems or ideas for a script. Important phone numbers and contacts were often scrawled on a crumpled Kleenex and tossed into the back of her car along with girdles, old plane boarding passes, unmatched shoes, and traffic tickets.

Left to her own devices Marilyn was sloppy in epic proportions. But under Amy’s roof she was “neat, clean, and no problem whatsoever.” Amy enjoyed taking charge of Marilyn, immediately addressing practical issues such as wardrobe. Like most other native Californians, Marilyn had no real winter clothes. “My friend, Annie Klein, who was a wonderful dress designer, had a ‘magic’ closet in her office on Seventh Avenue where she put all the fabrics that buyers were afraid to buy, too avant-garde or whatever, and there were only three people allowed in that closet. Annie one, me two, and a model that she had, called Reggie. It was Christmastime when Marilyn came to us, and I said, ‘Listen, I have a friend and she’s an actress—I never told Annie who it was—and I need some clothes because she has no fashion sense and I have to dress her up.’ And Annie said, ‘Come and get what you want.’ So I went to the offices, and I took about eight outfits, had them send to Connecticut. It went under the Christmas tree. And Christmas morning, she opened it up, and she was aghast. No one had ever done this for her before, ever. No one.”

“On Christmas Eve I took her into New York,” Milton remembered. “She saw all the stores, all the Christmas trees, all the lights. It was her first Christmas here. We started at Lord & Taylor, then worked our way up Fifth Avenue. It was very touching—she was like a little girl. She wore a coat and scarf, no makeup. She looked wonderful.”

On Christmas morning, Marilyn shuffled downstairs in furry winter slippers, wrapped in a baggy crewneck and a pair of Milton’s pants. Boxes, ribbons, and shiny paper were strewn under a bauble-laden tree. The phone rang off the hook with calls from LA—Frank Sinatra, Sidney Skolsky, Billy Wilder, and Bob Hope. Amy answered with feigned innocence while Marilyn and Milton giggled in the background. “Tell me, Mr. Hope,” she inquired coolly, “is Marilyn lost?” She hung up the phone and joined Marilyn on the floor, rolling and hooting with laughter.

The phone was still ringing when Milton formalized Marilyn Monroe Productions on New Year’s Eve 1954. It was official: Marilyn was in hiding.

* * *

After Milton Greene, Amy was Marilyn’s strongest supporter. Not only had Milton quit his steady job at Look—he had mortgaged his house and maxed out his credit to support Marilyn and their new production company. With a wife and a one-year-old son, this was the gamble of a lifetime, and Amy never batted an eye. MMP was their future, and she was ready to do whatever she could to help.

Her first order of business was giving Marilyn a makeover. Milton had long been exasperated with Marilyn’s wardrobe, which ricocheted from skintight to slovenly with little in between. “That looks like a schmatta,” he’d moan whenever she’d show him a dress. He begged her to stop passing out in her makeup and cajoled her into using the gold-plated hairbrush Sinatra had given her on her birthday. “Instead of being a slob,” he ordered, “act like a woman.”

“Look,” he insisted. “You have something that looks fantastic on screen, but you walk around like a slob. You want to be a great actress and you already are, but you have to carry yourself a certain way. Look at Katharine Hepburn—she has a certain style or class. You need a certain something, something other than cheap blonde sexpot. Now let’s go out and buy some clothes.”

So he drove her into Manhattan, hitting up Bergdorf’s, Bonwit Teller, and Saks. “She bought a dress at Bergdorf’s with a sheer panel that looked great. But then she’d never really wear it. She’d just go back to the old clothes she was used to—slacks cut too short that never really fit, blouses that never really had the right lines.”

Frustrated by wasting money on unworn clothes, Milton enlisted Amy’s help. A former model—who tucked her pearls into her neckline years before Jackie would—Amy was the ideal style mentor. Typical fashionista, she started with shoes: “I was the one who got her out of those dreadful shoes she always wore—round in front, closed in back, with a two-inch gap on the instep. Every star at Twentieth Century Fox wore those. I got her fifty pairs of Italian shoes at Dalco. Identical closed pump with a high spiked heel, maybe three-and-a-half inches long. I paid twenty bucks a pair for them, and she wore them for the rest of her life.”

Clothes were a little more complicated. The paltry trunk Marilyn had taken to New York failed to impress Amy—jeans from J.C. Penney and the Army surplus shop, puffed-sleeved dresses with babyish yokes, skintight sweaters thrown in with beige Don Loper suits and the bugle-beaded Cecil Chapman dress she’d worn onstage in Korea. To the sophisticated East Coast Amy, these clothes were nothing short of pitiful, though she soon realized why—Marilyn had barely updated her wardrobe since her starlet days. “Whenever she needed something to go out, she’d go to her friend in the wardrobe department at Twentieth. She’d borrow something, and then the next morning she’d bring it back with a $50 bill slipped in.” It would have been cheaper to buy her own dresses—but Marilyn didn’t plan that far ahead, and she knew she’d probably lose them anyway.

Amy thought it best to start with the basics. “I wanted to buy her cashmere sweaters, so I took her to a shop called the Separates Shop that my friend Bootsy Moffat ran in Westport. And she very quietly said, ‘Bring me one in 34, 36, and 38.’ Thirty-eight for a soft shapeless sweater, 36 for dinner parties, and 34 for national television. I said, ‘Christ, just take the 38.’ The tight sweaters—she always called those her ‘work clothes.’ I thought it was all nonsense.”

Marilyn had been dressing like this for years—squeezing into too-tight sizes, stitching marbles into her bra. “She’d try dresses on in size twelve, and if she liked it she’d buy it in a size ten,” wrote Shelley Winters, who went shopping with her in Hollywood. Shelley went hoarse begging Marilyn to buy the size that fit, but she’d always protest with “I’m bloated” or “I just drank three Cokes.”

Now here in Westport, Connecticut, Marilyn was up to her old tricks. “She would look at me out of the corner of her eye and say, ‘What don’t you like about it?’ And I’d say, ‘Well the ass is too tight, or the skirt is too short.’ She’d take my advice but with a grain of salt, and only up to a certain point. Then the ‘work clothes’ would come out again.”

“You’re already a star,” Amy would plead. “You can wear anything you want. You don’t have to show your ass; you don’t have to show your tits.” But Marilyn felt alienated by “respectable” high fashion, which tended to favor trim nymphs like Amy. She knew she’d never be “classy” or “elegant.” She knew she’d never be in Vogue. At the same time, she had zero interest in following trends—she was almost too beautiful to be a fashion icon. With mid-century trendsetters like Diana Vreeland, Wallis Simpson, Babe Paley, or even Jackie Kennedy in the early years, you always noticed the clothes before the woman. Marilyn knew instinctively how to flip that around. A dress, however beautiful, would always just be a flattering frame. It was her face, her body, her hair and skin that were on show. That’s why she always favored neutrals—even her tartiest frocks were in black, creamy whites, or camel with touches of bronze. Likewise, jewelry was just another distraction. “I don’t own even a little diamond the size of a pinhead,” she boasted to Modern Screen. In a time when short chokers were practically mandatory, Marilyn left her neck bare. The foundations for a classic style were already there. Amy just had to tease them out.

With her usual directness, Amy went straight to the source: the designers themselves. She invited George Nardiello and Norman Norell for dinner, and together they created Marilyn’s new wardrobe from scratch.

By the time he met Marilyn Monroe, Norman Norell had become one of the country’s top designers, equal to Cassini, Dior, and Balenciaga. His shapes were sexy but understated—shirtwaists, mermaid dresses, high-necked sheaths, and nautical flourishes—worlds away from the painted-on lamé and plunging cleavage Marilyn was used to. At first Norell was appalled by her trampy taste. “She wanted everything to look like a slip,” he said. “Everything had to be skintight; you had to reinforce every seam or everything would break.”

But he bonded with Marilyn over a mutual interest: theater. Back in the thirties, he’d dressed Gertrude Lawrence and Ilka Chase. “He would tell her about all the clothes and they’d discuss theater,” said Amy. “Norell and Marilyn spent hours together—they adored each other.” George Nardiello also loved dressing Marilyn: “She looked even more gorgeous without any makeup on, sitting around in this beat-up terrycloth bathrobe. I used to make her pancakes with caviar and sour cream.”

Every Sunday they’d meet by the Greenes’ roaring fire and work with Marilyn on her signature look. First they addressed figure problems, which Marilyn didn’t mind discussing openly. “She had a very long back and a very long waist,” remarked Amy, “which is interesting because she didn’t have a neck to speak of. But her thighs were lovely; she had really long tapering thighs. Norell once said to me, ‘She really has a wonderful body, but she doesn’t belong in this century.’ And he’s right—she’s totally a turn-of-the-century-type woman.” But Marilyn needed a modern wardrobe: tight but still classy, washable, packable, and neutral enough to allow for spontaneity.

The result was a capsule collection of black sheaths and slips, sexy but simple and perfectly in tune with Marilyn’s aesthetics. Each dress was skintight, just the way she liked it, but in Norell’s “slipper satin” sober black mattes they looked refreshingly natural—more curvy selkie than wanton bombshell. She liked them so much she had copies made, supplementing the couture originals with cheaper versions sewn by Seventh Avenue dressmakers. She loved the ease of a uniform, and though she’d mix in capris and skirts snagged from Anne Klein, she spent the next few months living in identical black slips.

Marilyn may have needed Amy’s fashion expertise, but with makeup she was pure maven. She’d been perfecting her beauty routine since her starving-model days—shampooing and setting her own hair, bleaching it with peroxide paste, disguising her botched nose job with layers of gray contour. She watched backstage stylists and tweaked what she’d learned, going rogue against the trends of the day. Instead of powdering her face to a faddish matte, she coated her cheekbones with Vaseline, lanolin, and olive oil. She approached makeup with the technical skill of an artist—it made sense that the director she loved best was a painter. The way Marilyn highlighted her eyes had more in common with da Vinci’s Madonna of the Rocks than with shadow tutorials in Vogue.

That winter Marilyn and Amy whiled away the hours giving each other makeovers. Cross-legged on the floor, they rummaged through Marilyn’s leatherette beauty kits—lipsticks by Max Factor, bobby pins, mini–squeeze bottles of Helena Rubinstein lash glue, white highlighter sticks, Liz Arden shadows in Autumn Smoke and Pearly Blue, Revlon nail polish in Hot Coral and Cherries à la Mode, and bristly brow brushes in robin-egg blue. Under the ambery glow of her portable beauty lamp, Marilyn lined Amy’s eyes with umber pencils and separated her lashes with tiny gold lash combs. As she worked on Amy, Marilyn refined her own look.

Away from iron-lacquered Hollywood, Marilyn cultivated a natural style. Lipstick went from Russian Red to pale pink. Contoured cheeks gave way to soft peachy blush and light flicks of mascara that let her natural beauty shine. She blonded her hair even paler, but gave it gravitas with plain black turtlenecks. She paired Amy’s effortless chic with Wuthering Heights meets Jean Harlow hair. Marilyn was confident, and she glowed.

While the fashion team worked on beauty and wardrobe, Milton took charge of media image. His barn studio flooded with natural light that matched Marilyn’s relaxed, off-duty bloom. She found freedom in the winter-lit barn; she didn’t have to be sexy or aloof for the camera. Unguarded, she let her emotions shine through and illuminate her. What emerged was a playful, vulnerable sensuality that was much more compelling than diamonds and cheesecake. He shot her invisibly naked under Amy’s loose pullover, red rayon fabric stretched over her knees; or feigning slumber in a tennis sweater, palms pressed together like a child’s. She posed between two sawhorses in a pinstriped button-up, hands clasped behind her neck.

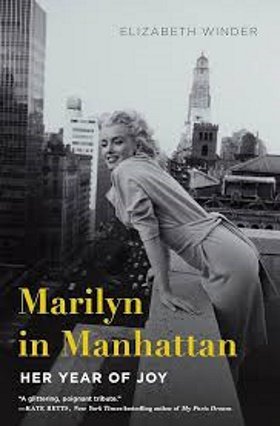

Sometimes they worked in his Manhattan studio, a nineteenth-century office building surrounded by Condé Nast offices and swank hotels. A friend once described Milton’s studio as “a cat burglar’s dream,” with its balconies, twenty-foot crenellated ceilings, and floor-length windows that swung open over bustling Midtown streets. More like Rome than New York, 480 Lex was a space full of Old World romance, where you could sip cocktails on the balcony or host long, Italian-peasant-style lunches. (Milton did both.) He’d pasted the walls with his photos from Vogue and Look, stuffed trunks with costume props full of old magic—the perfect environment for creating with Marilyn.

Their first photoshoot at 480 Lex—The Ballerina Sitting—occurred by happy accident. Marilyn was struggling with the zipper of an organza dress—one of the too-tight Anne Kleins Amy had given her. Inspired, Milton perched her on a wicker stool between horizontal rods that looked like dancers’ bars. Clutching the gauzy bodice to her milky skin, Marilyn looked like a sleepy ballerina.

This was Marilyn and Milton at their collaborative best—impromptu offhand glamour, cheeky but sweet. Barefoot and unzipped, Marilyn embodied the rough sensuality of offstage ballet: pink ribbons and leather, tights, old leotards and dusty practice rooms. Her naked feet look slightly swollen, her rolled shoulders suggest tired, touchable flesh. The zipper marks on her exposed back are red, raw, and provocative. In a time when women were groomed to perfection, this was sexy, undone, and completely modern.

Milton and Marilyn were ahead of their time, and they knew it. How soon would it take the world to catch up?