t o o l d s h o r e s ?

Married to a Jew, Detlef Sierck left Nazi Germany at the peak of his success at UFA in December 1937. He spent two years in Italy, Austria, and the Netherlands before Warner invited him to Hollywood in 1939 to shoot a remake of To New Shores, a project terminated in 1940. Sierck’s first American film assignment was a 1941 documentary on winemaking in a monas-tery in Napa Valley. The film traveled to Catholic parishes all over the United States. Even though most filmographies fail to list this production, it in all likelihood remains Sierck’s greatest popular success. Also in 1941

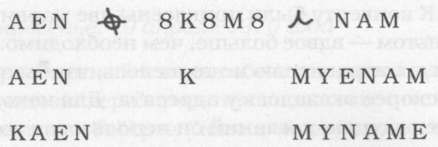

Detlef Sierck changed his name to Douglas Sirk. He dissociated his name from any German trace in order to accommodate Hollywood producers waging war against Hitler Germany and to appease the many German exiles who considered him a Nazi collaborator. In contrast to Max Ophüls , whose name experienced a series of dismemberments in exile (Ophuls, Opuls),10 Sirk’s cognominal redress signaled his eagerness to meet Hollywood more than halfway—to leave his past behind and excel in American culture on its own grounds.

“I was in love with America, and I often have a great nostalgia for it,” Sirk recalled in 1971. “I think I was one of the few German émigrés who came to America with a certain background of reading about the country and a great interest in it—and I was about the only one who got around and about.”11

Sirk’s move to Hollywood and change of name did not signify a radical rupture in his career. His preoccupation with America, as we have seen in chapter 3, had commenced long before his arrival in Hollywood. Films such as To New Shores and La Habanera had been deeply enmeshed in the ambivalent project of Nazi Americanism. Much of his Hollywood work, on the other hand, recalled and further developed the iconographic, thematic, and stylistic registers of his earlier films. It is in particular the use of organized religion as a sign for the popular (which, as I argued before, should not be automatically conflated with the category of industrial mass culture) that links Sirk’s German and Hollywood periods. In To New Shores religious material elicited the viewer’s desire for cultural synthesis. It conjured the vision of a new popular in which the divided tracks of modern culture—

aesthetic refinement and commodified diversion— could reunify. Similarly, in the melodramas of the 1950s Sirk’s references to organized religion

07-C2205 8/17/02 3:39 PM Page 209

Pianos, Priests, and Popular Culture

/

209

are part of a persistent inquiry into the divisions and utopian potentials of modern American culture. They reveal the status of melodrama as a paradoxical source of transcendence in a postsacred world12 but simultaneously express what Sirk considered the popular beliefs, meanings, and goals of American society.

Whereas films such as The First Legion (1951) or Battle Hymn (1956) directly address the delicate role of religious institutions in secularized America, other films are often literally framed by religious symbols. Church towers, for example, figure prominently in the opening shots of both All I Desire (1953) and All That Heaven Allows (1954). They set the stage on which small-town America regulates desire and molds conformity.13 In Imitation of Life (1959), on the other hand, religious sights and sounds provide anchors to those lost in the storms of passion and excess. “I see religion as a very important part of bourgeois society,” Sirk explained in an interview. “It is a pillar of this society, if a broken pillar. The marble is showing quite a bit of decay. If you want to make pictures about this society, I think it is an ingredient of a bygone charm— charm in the original sense of the word: sorcery.”14 Organized religion may have lost its hegemonic role in sanctifying norms and providing metaphysical securities, yet its symbols, according to Sirk, continue to speak to everyone. Sirk’s melodramas resort to religious signs to bind images, sounds, and narratives into affective expressions. They reconstruct the sacred in order to recenter experience and smooth over the divisions of modern society. The priest’s bygone sorcery thus reemerges as the magic of the film director who understands how to captivate the popular imagination and stir universal emotions. In the absence of a numinous center of things, melodrama reinscribes ethical imperatives that can operate as society’s post-traditional glue. It reclaims through Manichean intensification and aesthetic stylization what religious belief systems no longer uniformly authorize.

Released through United Artists in 1951, The First Legion occupies an odd place within this melodramatic theology. The film surely pictures organized religion as a source of healing, of restoring body and spirit in a time of fragmentation. In contrast to Battle Hymn or To New Shores, however, the film eschews any eschatological vision of cultural synthesis and, instead, denounces the popular as the antithesis of authentic meaning and culture. The film reserves healing for those who are able to remove themselves from the pleasures and secular institutions of modern life. It may render religion as a utopian blueprint of spiritual renewal, but it does so by means of a stunningly elitist gesture—by radically separating religious from profane experience, theology from the popular. Like Wagner, for

07-C2205 8/17/02 3:39 PM Page 210

210

/

Berlin in Hollywood, 1939 –1955

whom the secluded Bayreuth festival was to counteract the commercialization of nineteenth-century art, Sirk challenges in The First Legion the profanity of modern culture from the vantage point of a sequestered monas-tery and its necessarily esoteric access to salvation.

Filmed entirely on location at Mission Inn, Riverside, California, The First Legion was originally shot as an independent production in 1950. The film confronts the viewer with a number of rather unlikely Jesuits—a former criminal attorney, an ex-concert pianist, an India traveler cum film director—who find themselves forced to revise their standards of belief after experiencing first a makeshift and later a “real” miracle. On a formal level The First Legion stages this concern with the issue of faith, redemption, and the absurd by interrogating different regimes of vision and hearing.

Reminiscent of To New Shores, Sirk is at pains in this later production to distinguish between authentic and inauthentic modes of sense perception.

Whereas the fake miracle and its initial mass popularity correspond to forms of sentience skewered by the logic of the market, the true miracle in the end represents the work of an introspective, contemplative form of audiovision that resists the spell of visual and auditory spectacle.

The Jesuit seminary is introduced as a space of expressive authenticity and high cultural distinction. An enthusiast of classical music, Father Fulton (Wesley Addy) responds to the first miracle not with words of prayer but by playing Edvard Grieg’s Piano Sonata in A minor. In a curiously disembodied shot Sirk’s camera shows us the labor of Fulton’s hands on the keyboard as if to underscore the work that is true art. Attracted to the alleged site of salvation, the masses outside the seminary, on the other hand, hope to consume the miracle as distraction and cultural commodity—a thing they can stick in their pockets and take home. Transformed into a media spectacle, the miracle here generates a delusory experience of social harmony and charismatic wholeness. In the crowd’s populist desire for individual redemption and community, repression and wish fulfillment, fantasy and symbolic containment join together in one mechanism.

Installed on the roof of the seminary, Father Fulton compares the people outside the gate with the murmur of the crowd before a symphonic concert, the hum of a great orchestra, with the one exception that the boundaries between spectacle and audience have broken down and the crowd has become its own object of delight. Looking at the masses and cameras looking at the seminary, Father Fulton welcomes the Jesuits’ sudden media stardom as a sign of rejuvenation. Being looked at reinvigorates Fulton’s faith and mission; it overcomes the Jesuits’ progressive isolation in a secularized world. Father Arnoux (Charles Boyer), by way of contrast, otherwise con-

07-C2205 8/17/02 3:39 PM Page 211

Pianos, Priests, and Popular Culture

/

211

Figure 26. Theology reconsidered: Charles Boyer and Wesley Addy in Douglas Sirk’s The First Legion (1951). Courtesy of Filmmuseum Berlin—Deutsche Kinemathek.

cerned with reconnecting the Jesuits to the timetables of the modern world, makes no secret of his disdain for the crowd outside. Fulton’s hum, in Arnoux’s perception, sounds more “like music that has swept you off your feet.” Arnoux, in his controversial tractates, may argue for a liberalization of church doctrine, but his agenda is to bring the Jesuits to the world, not the world to the Jesuits. Media popularity, for Arnoux, bereaves the Jesuits of what is at the core of their mission. The spectacle disables communication and emotional authenticity. It blocks the resurrection of contemplative spaces in which true recognition and healing might be possible. For Arnoux, Fulton’s populism effaces what transcends the given moment and thus diverts from the exertion necessary to achieve salvation (fig. 26).

“All right, I am out of joint like the rest of the world,” Doctor Morrell, the forger of the first miracle, confesses in a climactic moment to Father Arnoux. “Nothing adds up to anything anymore.” Like To New Shores, The First Legion offers an image of modern culture torn into hostile halves, halves that long to reconcile themselves within a higher organic totality.

Whereas the crowd outside the seminary desires the priests’ alleged bliss

07-C2205 8/17/02 3:39 PM Page 212

212

/

Berlin in Hollywood, 1939 –1955

of charismatic experience, some of the fathers inside hope to reconnect their esoteric practice to the popular dimension. In contrast to the final images of Sirk’s earlier film, however, The First Legion leaves little doubt that such a mutual integration of high and low will result in anything but a false unity, in delusion rather than insight or redemption. The division of modern culture is its truth, and the task of any authentic cultural practice is to work through, not to gloss over, the split that marks the modern condition.

It is important to note in this context that the first—the fake—miracle happens precisely when the priests assemble in the seminary’s meeting room to watch one of Father Quarterman’s films shot during his travels in India. Holy people in India, Quarterman lectures, “capture the soul by capturing the imagination.” And so does this film within the film, transforming the sacred into a direct effect of mechanical reproduction. Father Sierra appears suddenly from behind the space of projection, his presence on the staircase—his miraculous recovery of walking— coinciding with the image of an elephant strolling triumphantly across the screen. Captured by the cinematic image, the fathers’ imagination eclipses their critical reason.

Their desire to see and hear what cannot be perceived thus results in collective hypnosis. What they take as a charismatic intervention in fact constitutes a mere extension of screen reality.

Father Quarterman’s cinema aspires to open the enclosed world of the seminary toward the popular. It induces the priests to reshape the real as an imaginary space of wish fulfillment and plenitude. At the same time, however, it replicates within the seminary itself the very separation that structures social relations at large. Transforming spiritual values into flat surfaces, Quarterman’s projection literally cuts the meeting room in half.15